What happens when wildly popular videogames make a run at the gatekeepers of the artworld?

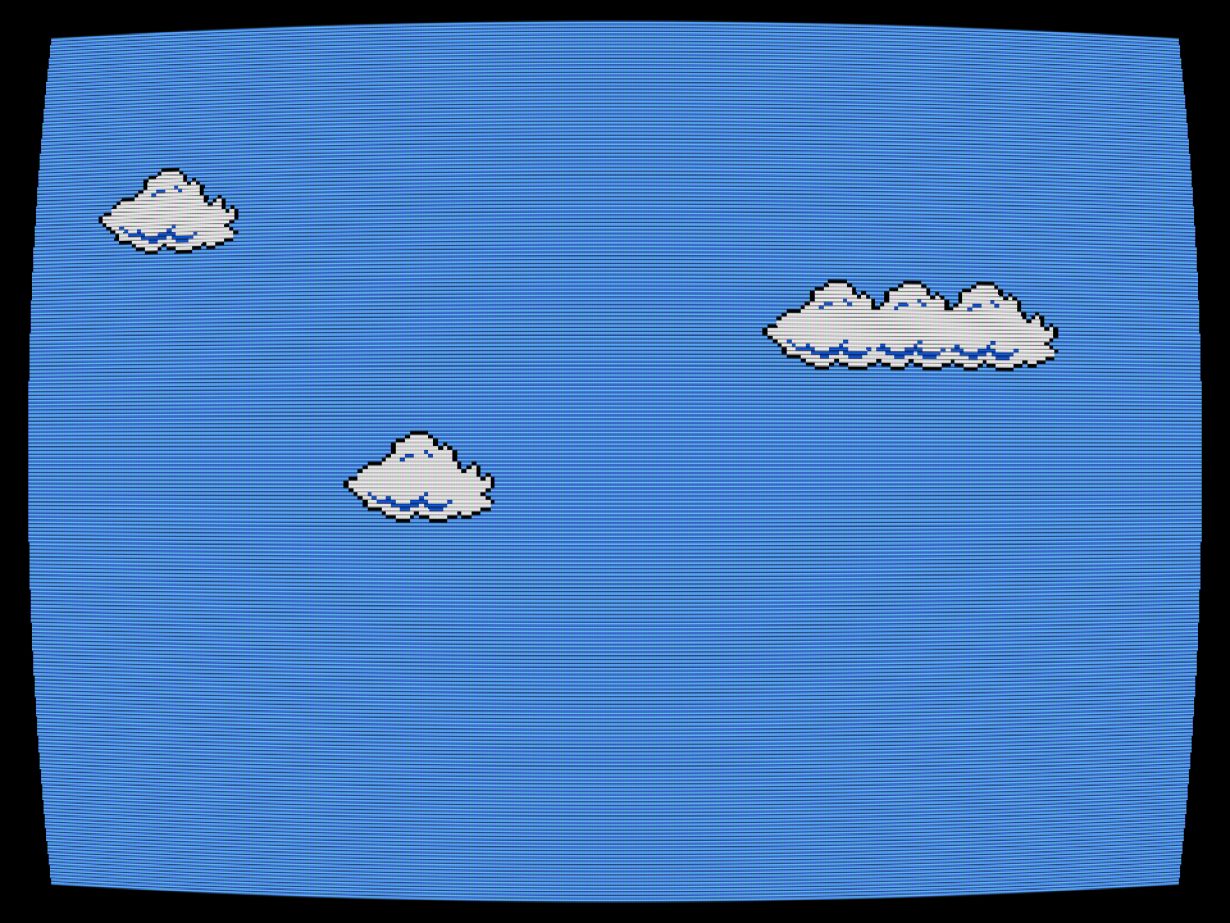

In March 2009, Cory Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds (2002) appeared on the cover of Artforum, signalling that videogames had finally ‘made it’ into art discourse proper. All Arcangel had to do was jettison almost every element (ground, trees, powerups, monsters and Mario himself) that had earned the original Super Mario Brothers cartridge a ‘Nintendo Seal of Approval’ to make it into a video edition. While there were earlier and arguably more provocative Mario hacks, such as Myfanwy Ashmore’s Super Mario Trilogy (2000–04) – an existential-nightmare modification of the game in which Mario lives and dies without the performance-enhancing drugs that allow him to reach the level-ending flag – Arcangel’s Clouds are benign and boring, more Abstract Expressionist colour-field than side-scroller.

This comparison – Arcangel’s versus Ashmore’s Mario – offers a provocative lens through which to play recent high-profile videogame artworks. One such work, Gabriel Massan’s Third World: The Bottom Dimension (2023), a free-to-play downloadable videogame made for the Serpentine’s 2023 exhibition of the same name, marked a significant moment in the history of videogame art. Not so much because of its content, but more in its high-profile participation in the ‘play-to-earn’ gaming genre as conspicuous cultural capitalism. The game features a playable character named Funfun (Yoruba for ‘white’) – a hybrid robot-organic construct navigating a dynamically shifting alien landscape. The Unreal Engine-generated habitats of fungi and rock grow, morph and decay much like so many pop-cultural dystopian landscapes, nodding to such sublime horrors as the DNA-altering ‘shimmer’ in Alex Garland’s film Annihilation (2018), the fungal mutations in The Last of Us television (2023–) and videogame (2013) series, as well as the eldritch trappings of games like Elden Ring (2022) and Death Stranding (2019).

Though its recognisable imagery offers an entry point for a video-game-enthused audience, the game and its installations reference a messy bibliography of Brazilian critical race theory and pedagogy, all strained through Avatar-flavoured issues of ‘extractivism’. Yet ironically, while the undeniably dazzling imagery of Third World’s environment bears little resemblance to Arcangel’s Clouds, the ‘play-to-earn’ format of Massan’s downloadable game is another kind of capitulation. Ashmore’s central decision to delete Mario’s powerups, leaving the character vulnerable and lost in a world of plumbing and pitfalls, contrasts sharply with the function of Third World’s regrettable ‘Mint Your Memory’ feature, where players were able to create Web3 tokens powered by cryptocurrency Tezos by capturing screenshots within the game. Despite the proliferation of such ‘play-to-earn’ gimmicks in the casual gaming genre, the press release of Third World boasted the minting as a novel form of audience participation, an augmented-reality twist in Funfun’s – and thus the player’s – in-game collecting quest.

It is Funfun’s ‘employer’, the company with the too-on-the-nose name ‘Digital Worlds Exploitation’, that narratively provides the in-game equipment to take these screen captures (or ‘memories’). But this real-world introduction of these memories as minted NFTs for the player to share (#ThirdWorld) undermines an otherwise well-meaning, though pedantic, narrative of transmutation and redemption. In addition, the social justice-coded marketing behind this crypto element unconvincingly proposes that Tezos’s blockchain technology is ‘energy-efficient’ (at least compared to the reprehensibly power-hungry dominant blockchain model of Bitcoin). Regardless of its alternative pedagogies and ecological resource depletion narrative, the same old arbiters of taste and influence still call the shots. In this case, Third World trades blue-chip gallerists and their wealthy collectors for an arguably more ethically challenged techno-cabal of crypto-anarchists.

The convergence of videogames and art raises broader questions about universalism versus intersectionality, interactivity and performance in art spaces, and the ethical standard of access and equity. Journalist Bianca Bosker’s new book, Get in the Picture – published 20 years after Arcangel’s Clouds debuted at the 2004 Whitney Biennial – catalogues her insights from five years spent embedded in the New York art scene. It becomes apparent that what is still at issue is who is allowed into – or otherwise left out of – the artworld. Bosker cites how gatekeeping language emphasises a deep knowledge of rarefied historical and cultural context, and prioritises those ‘in the know’, the connoisseurs and gallerists whose financial stability depends upon exclusivity. Videogames, by contrast, are wildly popular worldwide. Consider the lasting popularity of tactical first-person shooters such as the Counter-Strike (2000–) and Call of Duty (2003–) franchises, which have earned billions of dollars in revenue.

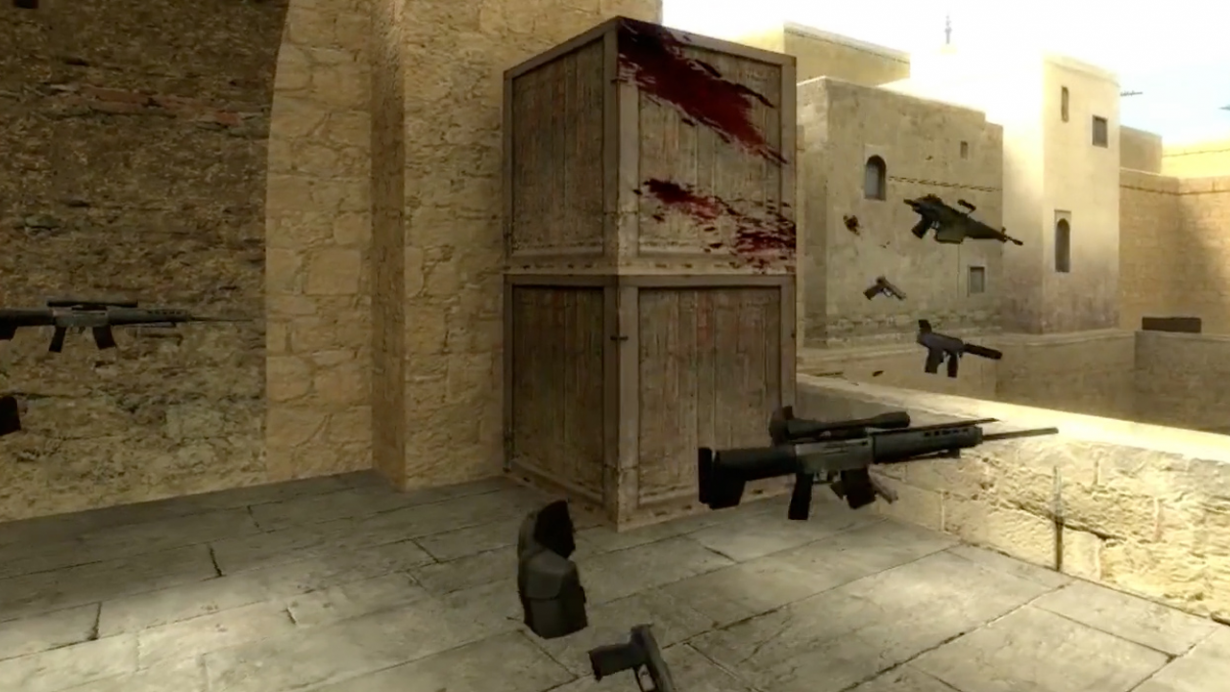

Videogame art has a long history of modifying popular titles in this genre, offering accessible and engaging contemporary critique for otherwise difficult and divisive subject matter. Kent Sheely’s Counter-Strike mod, dust2_dust (2013), for example, erases all figural representation from play, but leaves weaponry intact: gone are all playable characters and nonplayable characters, as we witness disembodied, bobbing and weaving guns, spreading pools and sprays of blood, and the sounds of gunshots and cries of agony. After the shock of its absurdity wanes, the piece begins to relate more to how drone warfare and forms of technologically mediated violence erase signifiers of human suffering from popular media.

Until recently, Sheely’s dust2_ dust and similar ‘game performances’, such as screen recordings, playable modifications of popular games, web-based emulators and Machinima (animations made using videogame toolkits), lived in spaces between screenings and game-specific festivals. While videogames by established artists had already found their way into the white cube – Bill Viola’s The Night Journey (2007) comes to mind – a more inclusive form of games as art began popping up in alternative gallery spaces during the mid- to late 2000s. Unlike the conventional art galleries Bosker describes, venues like Killscreen (Los Angeles), Babycastles (New York) and VGA Gallery (Chicago), and festivals like Now Play This (London), Bit Bash (Chicago), Vector (Toronto), A Maze (Berlin) and EyeMyth (various locations in India) popularised work by artists from historically marginalised communities and regions. A few short years later, these same independent videogame arts organisations began facilitating videogame art retrospectives in established museums, such as the Victoria & Albert Museum’s 2018 exhibition Videogames: Design/Play/Disrupt.

One of the V&A’s commissioned works for the exhibition, In the Pause between the Ringing (2019), by the India-based Studio Oleomingus, is a meditation on the turbulent history of telephone mining in British India. Its innovative gameplay combines the formats of interactive fiction, audio drama and exploratory games. Unlike Third World, the beautiful but surreal imagery of Ringing’s oversize telephones and brilliantly coloured colonial architecture provides ambiguous narrative cues through its sound design rather than narration or dialogue. Instead of scrambling towards future technological innovation, Dhruv Jani, founder of Oleomingus, described in a talk at the 2019 EyeMyth in Mumbai how the very building blocks of our digital age, hyper-text and interactive fiction (aka the text adventure genre, the earliest form of videogame interactivity), provide the opportunity to radically rewrite, overwrite and interject into dominant narratives that perpetuate human suffering from the past into the present: “Hypertext, in its purest form,” Jani argued, “is the first methodical repudiation of the tyranny of the printed word… Especially when history and often immediate history is being ruthlessly deployed to create rigid boundaries, efface people and places, and to prop up governments based on the written word, the linear page, the archaic printed ideal.”

Even barring playable elements, a videogame installation can hold the unique power of generating nonlinear, rhizomatic narratives in the service of voicing the lived realities of the disempowered. Sondra Perry’s digital installation IT’S IN THE GAME ’17 or Mirror Gag for Vitrine and Projection (2017) echoes videogame developer EA Sports’ aggressive game tagline ‘It’s in the Game’ to emphasise how black bodies are represented in videogames. The installation tells how Sandy Perry, Sondra’s twin brother, was a college basketball player whose physical likeness and statistics were sold by the National Collegiate Athletic Association to EA Sports for use in the 2009 and 2010 NCAA videogames without his knowledge or consent. Despite a class action lawsuit, none of the players featured in the game were ever paid by the NCAA, who claimed that the players had been given compensation through a free education and thus had no legal standing. The anecdote serves as a disturbing, unresolved funhouse-mirror version of Jordan Peele’s film Get Out (2017), where black bodies are literally hijacked by wealthy white patrons. Perry’s video documents Sandy navigating a team-selection screen in the game while he describes his close friendships with the men whose likenesses continue to be exploited.

As the artworld grapples with issues of elitism and exclusivity, its continued emphasis on technologically novel forms of interactivity – such as the integration of NFTs and blockchain technology – simply introduces exclusivity in another form, and botches the opportunity to consider how increasingly accessible videogame toolkits offer otherwise alienated communities a chance to participate in, and perhaps redefine, the artworld. While those of us who feel strongly about the potential of videogames residing in art galleries are still wrestling with what constitutes meaningful interactivity in digital art, this emphasis on gimmicks and bleeding-edge methods risks overshadowing the genuine potential of videogames to engage audiences in meaningful conversations about complex and uncomfortable subjects. As the resident alien in the gallery, the videogame artwork needn’t fit in before it finds its appropriately alien audience.

Tiffany Funk is an artist, theorist and researcher based in Chicago