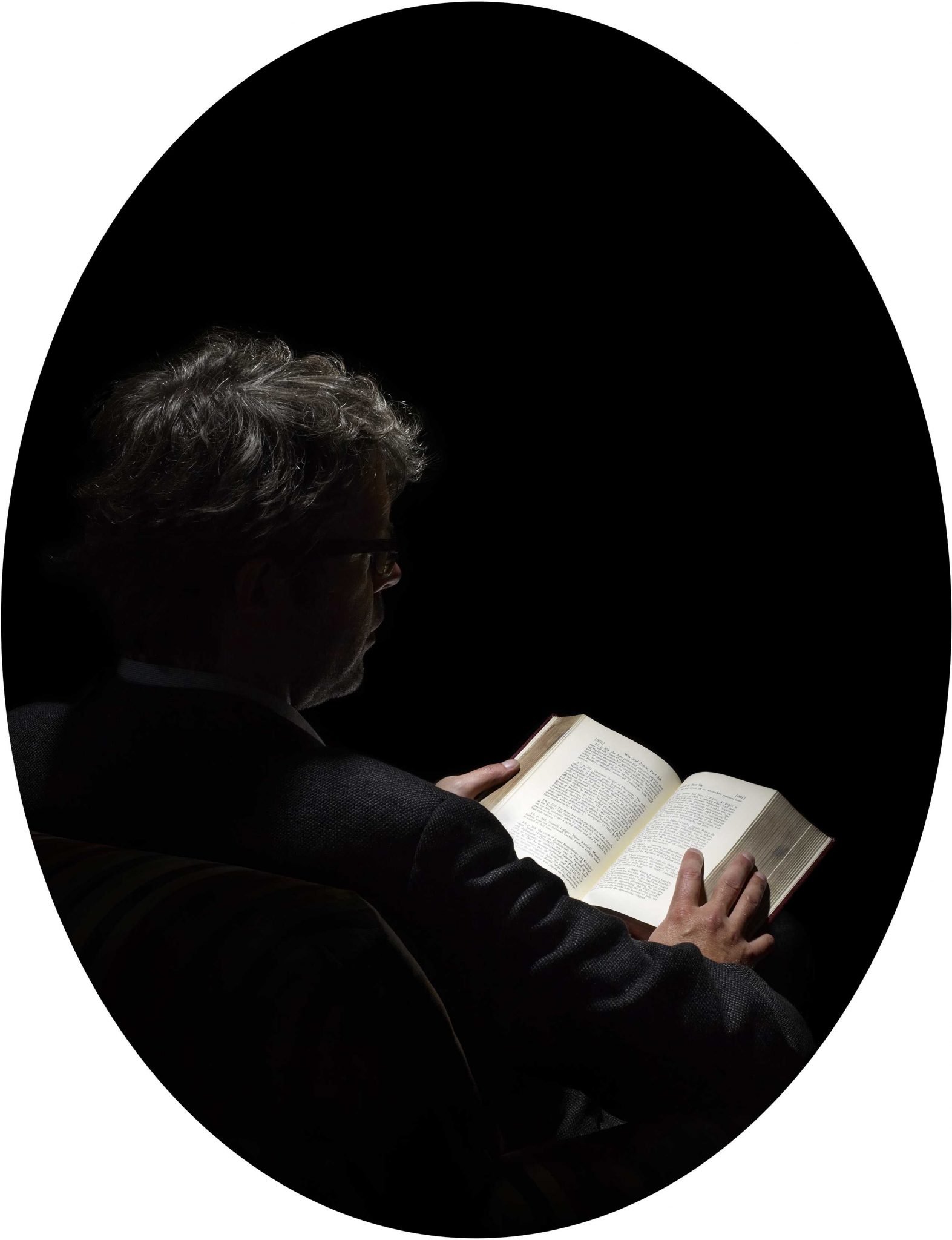

How could one not be intrigued by Jonathan Franzen’s appearance in Catherine Opie’s new series of photographs? The writer sits, in lost profile, absorbed by Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869), which is soaked in a bath of light. Franzen is a secondary concern in the photograph. In this instance, he is less capable of being ‘known’ than the pages of the book, to which he is a servant. He waits, on the fringes of the light and mostly out of view, for the book to reveal its secrets – he appears to believe it is a proper vessel of enlightenment.

Opie, like Franzen, neither shies away from nor is enraptured by the trappings of irony and distance, but she nevertheless believes that realism, when employed with rigour and sensitivity, is an essential window to who we are right now. Whether in photographs of the sinuous lines of Los Angeles freeways, close family or a tight-knit S/M community that relies most of all on the trust its members have in each other, Opie is one of the foremost traditional photographers in America.

Her new show flickers back and forth between photography’s capacity for great doubt over its status as a conveyer of humanistic depth and its concomitant unapologetic embrace of that depth. Each wall of the Regen presentation contains an untitled landscape, which is distorted and rendered out of focus, and surrounded by subtly lit portraits against velvet backdrops. Great distances resolve into focus in two ways: first, through a manipulation of the mechanism of photography itself; second, through the human connection between Opie and her subject. The show, at its often-dark heart, is balanced between sustained mystery and intimacy.

The story is that this body of work grew out of Opie’s encounters in London with Gerhard Richter’s Tate Modern retrospective and the National Gallery’s show of Leonardo da Vinci. Opie’s show fully embodies both Leonardo’s exuberant belief that he could discover humanity’s essence through science and representation, and Richter’s sober doubts, figured in work that exemplifies how horrible memories outrun our capacity to represent them.

It would be pat to say that Opie just engages this duality by presenting simple Richteresque blurs next to her portraits; instead, she really wants the genuine fire of doubt, and she wants it to animate and charge her straight-ahead realism.

The portraits in the show – some of longtime subjects such as a woman named Idexa or Opie’s son, Oliver – emerge out of various states of shadow, as if each sitter’s character is appearing out of a bath of photographic solution and coming forward into the soft light of Opie’s gaze. She loves these people. Her moves with the camera are attuned and subtle. She watches and waits for her subjects to find themselves in the camera, and she waits to find them and be surprised by them. One assumes that the still life Stump Fire #1 (2012) is what Opie seeks: that moment when her subjects burst into the flame of their own internal light, and when photography becomes keeper of the fire.

Regen Projects, Los Angeles 23 February – 29 March 2013

This article was first published in the May 2013 issue of ArtReview