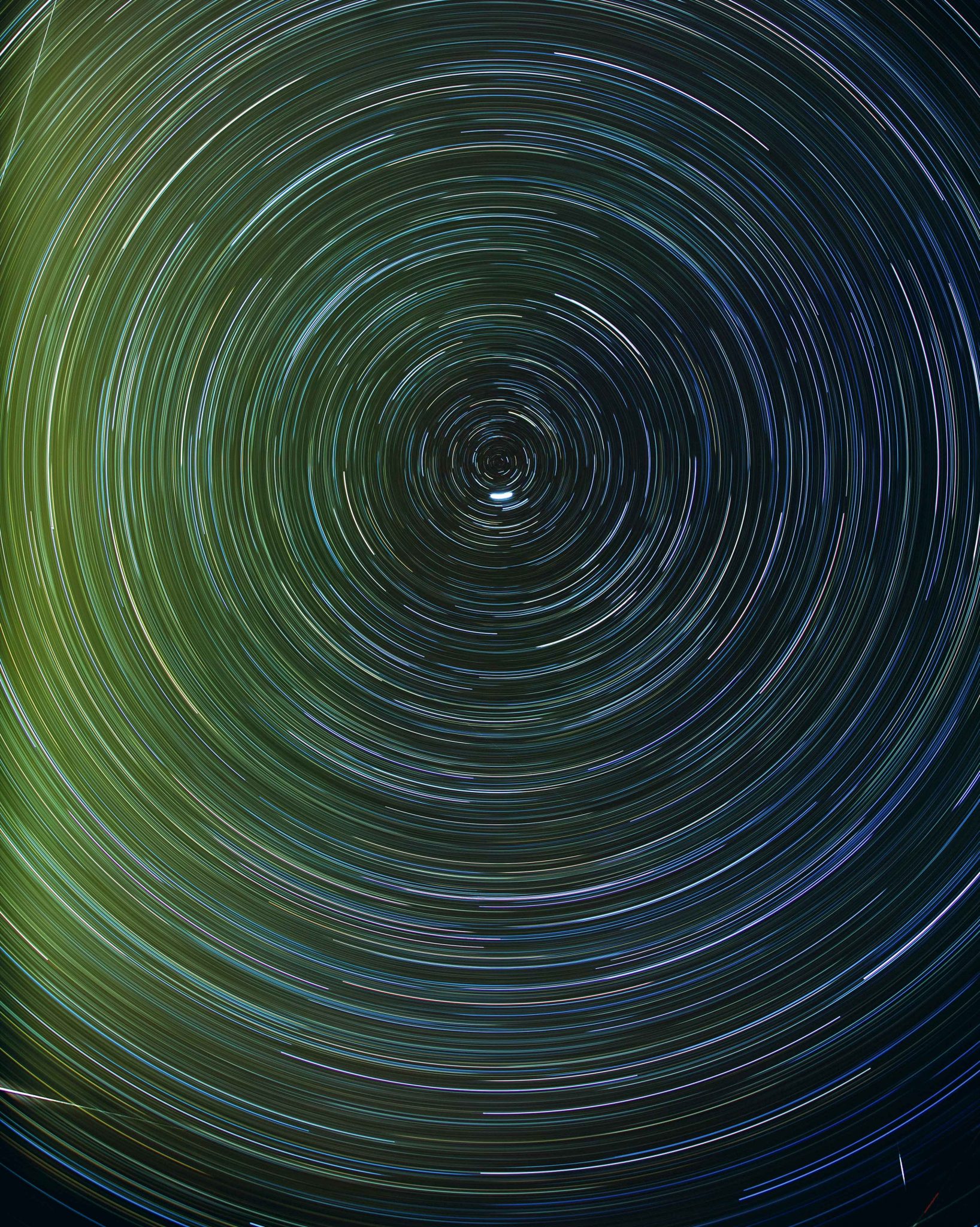

Artist and geographer Trevor Paglen has developed some of the most potent cultural critique available today. Witness his photographs of ‘black sites’ and spy satellites, which he shoots through telephoto lenses and telescopes. These images not only reveal the traces of our clandestine surveillance state – small dots of geosynchronous objects in orbit; hazy images of unmarked planes – but also, in their spooky emptiness, give form to the paranoia that haunts our society under the cloak of the War on Terror.

In this exhibition, Paglen expands his analysis of this contemporary ethos into a contemplation of man and time. Its core is a series of 100 images, The Last Pictures (2012), which Paglen has etched onto a silicate plate that was lofted into orbit last November in cooperation with a team of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). With pictures of tornadoes and crashing waves, people seen through the sights of a predator drone and grand constructions like the Hoover Dam, this time capsule presents life as a mix of disaster and Ozymandias-like overreach. The folly of human efforts to record, systematise and thus control such chaos is suggested both by a page from a dictionary of Volapük, a failed nineteenth-century attempt to establish a universal language, and a detail of Bruegel’s The Tower of Babel (1563), from which all of the figures were digitally excised. Their contemporary equivalent is the National Security Agency Data Center, now under construction in Utah, at which the government will collect and analyse our digital footprints in an effort to ensure public safety.

Beyond his mistrust of images and his obvious critiques of hubris and political malfeasance, Paglen is reaching for the mystery of ‘how special it is to be here now’, as one of his MIT collaborators puts it. A photograph of a lush riverbank points to the last paragraph of On the Origin of Species (1859), in which Darwin argues that life is not reducible to scientific certainty. Yet this show relies on the interpretation of visual information. It is laid out as an illustrated essay accompanied by an annotated checklist, and the artist never acknowledges that his work reflects the same need to convey content that motivates most societies, and people, to make and look at images. Ultimately, it is the fear of annihilation and nothingness that impels this urgency, just as it drives the dread that Paglen explores in his black-op photos. Failing to clinch the connection in his new work, Paglen falls short of the spiritual truth that lies beyond the limits of his own medium.

This article was first published in the May 2013 issue.