The Mexican American artist grapples with his own identity among the New York art scene of the 1980s in a book that is haunted by longing and loss

I suppose the word that comes to mind is ‘family’. As I leaf through the pages of this book, the names and voices of the American artist Roberto Juarez, his artist friends working in the East Village and the people who had the chance to meet them intertwine in a story that increasingly takes on the features of a family album. And like all family albums, this compelling collection of texts and artworks edited by Fabio Cherstich is entrusted with sampling places, people and situations: of the 1980s New York art scene, its studios and exhibitions, artists and galleries; the Lower East Side’s gay bars; pages from gay liberation magazine Fag Rag – a spiderweb composed of dazzling initial encounters and passionate friendships.

But it’s a paradoxical monograph, since while it’s ostensibly the story of Roberto Juarez, which contains within it the story of his group of friends, it ends up becoming a study of a group of artists. Cherstich comments on the relational nature of Juarez’s identity as an artist and person, such that his life and work cannot be separated from the East Village art scene and the New York queer community devastated by the AIDS crisis, nor from the glam-rock fluidity that informed him or his Latino roots. As it emerges from the materials that compose the book, Juarez is simultaneously an artist (whose paintings are analysed through the lens of art history by Edward J. Sullivan in a critical text); a friend (who poses with his arm around artist Jimmy Wright’s shoulder in a photograph taken during the early 1970s); and a confidant (of longtime friend Mark Tambella; captured here via an interview).

The book is published in conjunction with two exhibitions that opened in Italy during 2023–24 (at Apalazzo Gallery, in Brescia, and Palazzo Tiepolo, Venice). During lockdown, Juarez rediscovered oil-on-paper works made between 1981 and 1985. The paintings had been in storage for four decades. Twenty-five of these form the core of the book, and are recounted by Juarez himself through brief thoughts arranged alongside the reproductions. The paintings are an investigation of Latino identity in New York by a Mexican American who feels neither American nor Latin enough: Pac Man Pico (1984), for example, presents an orange ghost and a Pac-Man (respectively the victim and executioner from the popular 1980s videogame), surrounded by three packets of El Pico coffee, a drink popular with Latinos in New York. Thus, Juarez comments on Latino American identity as not comprising enough of either, and on the violence of their coexistence.

The book also deals with queer identity; bodies in the paintings are rendered in vivid colours like red and green, shapes are primitive, built with paint and layers of brushstrokes. The bodies are strong, mostly male – even Mother Nature in Earth Mother (1983) looks like a bodybuilder. Desire is palpable even if it always exists alongside a fear of contagion. In Phone Sex (1984), a little red man holds a disproportionately large erect penis in both hands, above a rotary telephone: an exiled desire, as well as a profound longing to be connected to another. This feeling haunts the pages of this book, and together with the frequent mention of his close friend Arch Connelly, who died of AIDS in 1993, inflects the narrative with a mournful tone. Through such haunted pages, the disappearance of a whole generation that vanished in a matter of years is felt – and it is still painful.

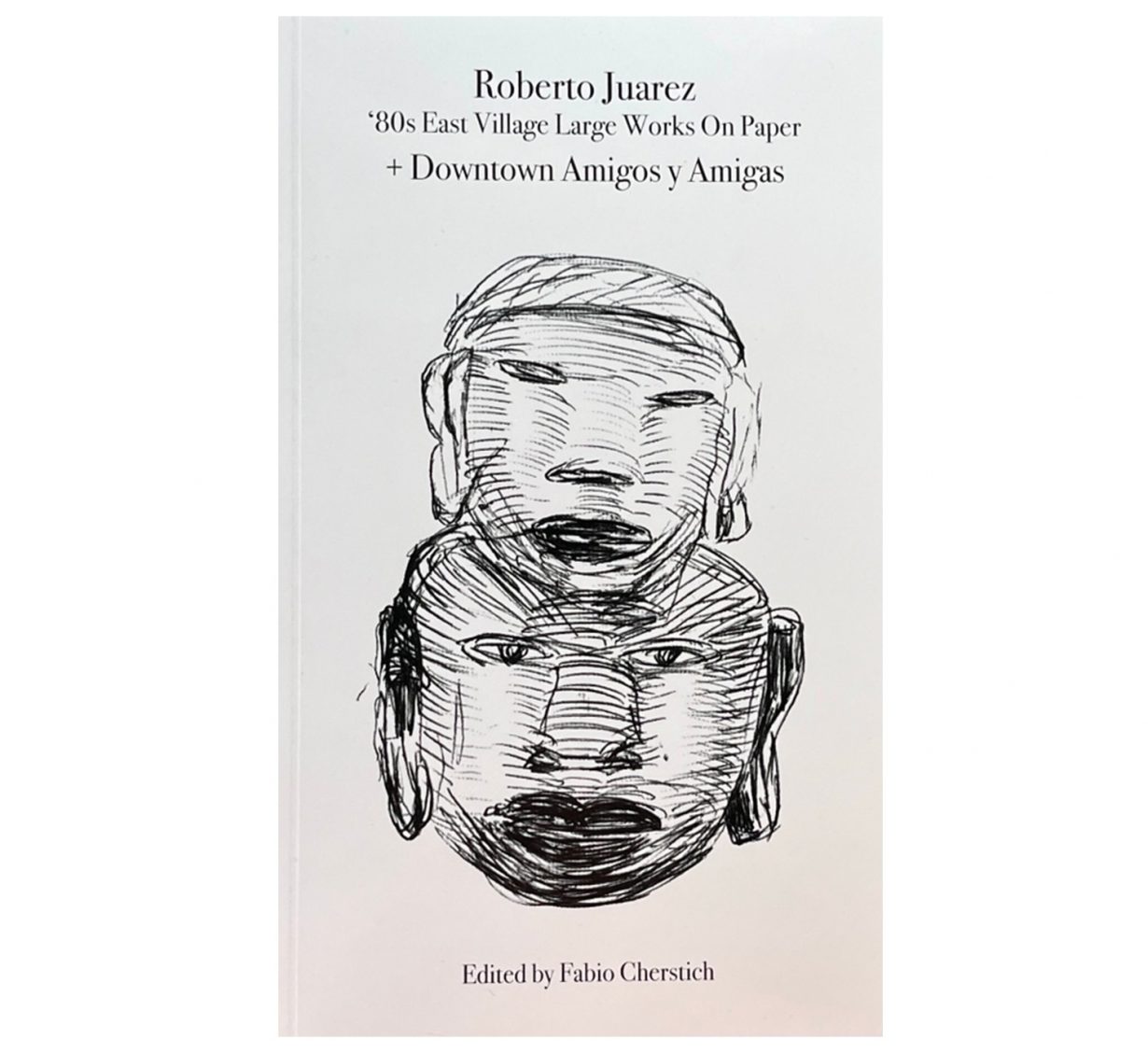

Roberto Juarez ’80s East Village Large Works On Paper + Downtown Amigos y Amigas. Edited by Fabio Cherstich Fabio Cherstich, $25 (softcover)