‘I realised there was no subversion without ideas. It’s not enough to want to destroy everything.’

Vivienne Westwood sewed her own wedding dress when she married her first husband, Derek, in July 1962. It’s hard not to speculate what that dress might have looked like – probably not provocative in the mould of her early punk years, but corseted perhaps, in her later signature style, or dramatically structured like the Westwood bridal gown in which Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw famously gets jilted at the altar. Whatever the case, the marriage didn’t last and poor Derek Westwood – an apprentice at the Hoover factory in West London – didn’t stand a chance, especially when bedraggled, firebrand art student Malcolm McLaren turned up on the scene, setting up shop with Vivienne and kickstarting the subcultural scene of mid-century Britain. Since then, and for nearly 60 years Westwood has been the queen of contemporary fashion. Her death in December 2022, at the age of 81, marks the end of an era.

Born Vivienne Isabel Swire in Glossop, Derbyshire in 1941, she grew up in the village of Tintwistle. Her father Gordon was a greengrocer among other things. Her mother Dora, who worked in a cotton mill, loved ballroom dancing. Westwood recalled her bringing back miscellaneous materials and sewing sumptuous dresses. At home in Tintwistle, there were cupboards crammed with voluminous nets and crushed silk, squashed next to sensible tweeds and Wellington boots. The adult Westwood loved them all. Her clothes were infused with a nostalgia for the hardy heritage of country clothing – Harris tweed, especially – and there was a magpie-ish quality in her impulse to embellish with colour, crowns, sashes and medals. The family moved to Harrow in Greater London in 1958, but the English countryside was formative to her imagination, fixed, like her northern accent, throughout her journey from the Peak District to the heart of punk.

Westwood never undertook any formal training in dress-making. But she was naturally gifted with her hands and her eye, an autodidact with a curiosity for culture, ideas and artistry. McLaren encouraged her to bleach her hair blonde and talked endlessly about Jackson Pollock and Jean-Paul Sartre. If French Situationism and American pop culture had had their moment in the late 1960s, they wondered, what could a counter-culture look like in modern Britain?

The answer was a little boutique on the Kings Road, first called ‘Let it Rock’, later known as ‘SEX’ and ‘Seditionaries’ in its various iterations. Borrowing money from her parents, they opened in 1971 and painted the shop black. Chelsea, at the time, was a jostling array of junk shops, floppy brimmed hats and psychedelic prints, but Westwood had a different vision. They began by selling 1950s memorabilia and second-hand clothes that Westwood would deftly repair and refashion, turning flares into straight leg trousers. David Bowie, Iggy Pop and Bryan Ferry would pop by, and filmmaker Ken Russell commissioned costumes.

Westwood, with her spiky blond hair, was at the helm. She wore tight leather trousers and a lemon mohair sweater, a look that she described to Vogue as ‘an Easter chick on acid.’ Later, they would experiment with rocker and biker looks, turning to latex, rubber and fetish. Westwood was stencilling slogans on the wall, hand printing T-shirts of Karl Marx, defacing portraits of the Queen, ransacking high and low culture and finding her own form of Dadaist provocation. ‘Seditionaries’ read the brass plaque on the wall outside, ‘is: for soldiers, prostitutes, dykes, and punks.’

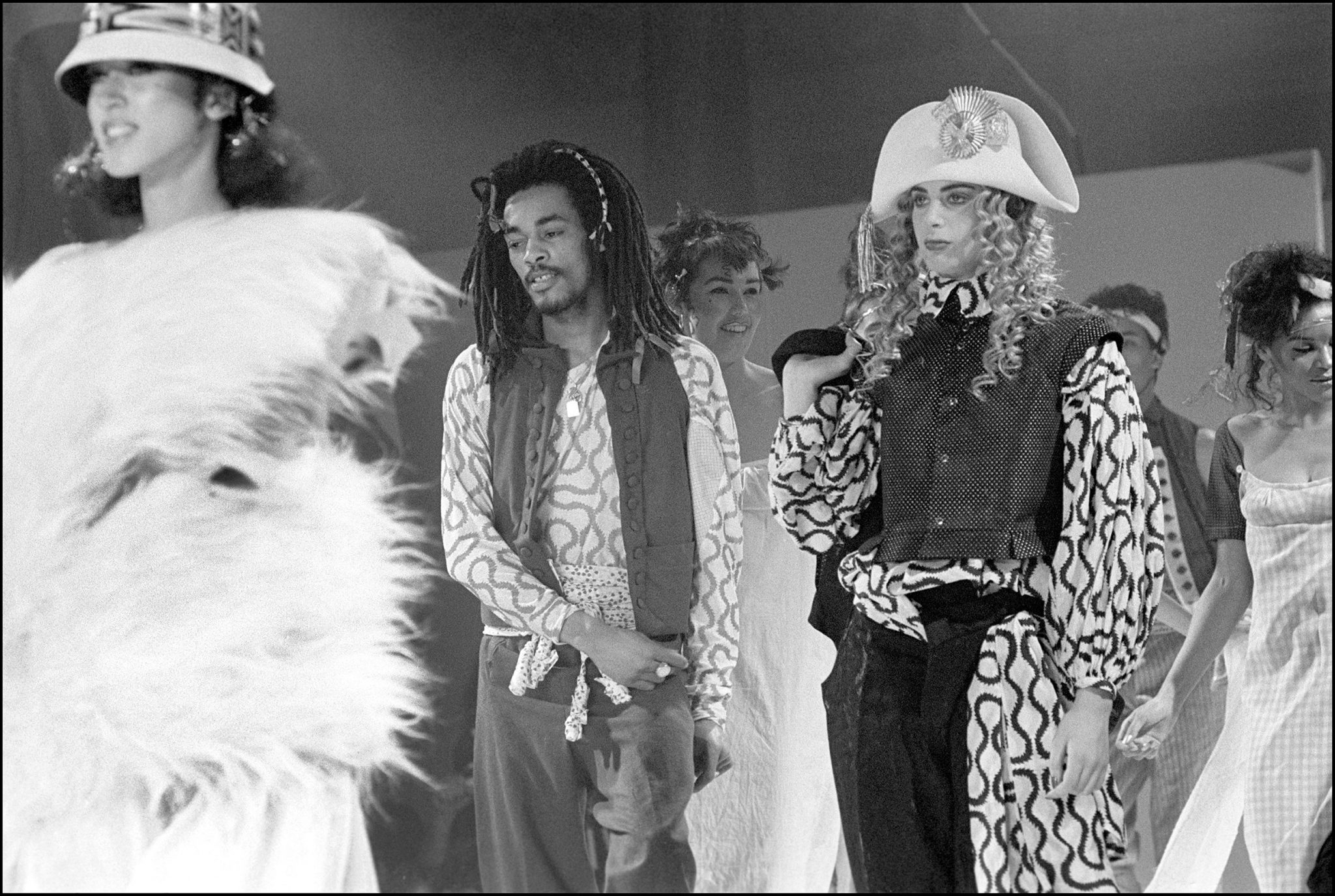

Reflecting on that time, Westwood noted that ‘it changed the way people looked. I was messianic about punk, seeing if one could put a spoke in the system in some way. I realised there was no subversion without ideas. It’s not enough to want to destroy everything’. Splitting from McLaren, she turned her attention to making fashion as punk gave way to new romanticism. Her ‘Pirates’ collection for Autumn/Winter 1981 with its billowing shirts studiously drew from eighteenth-century menswear, North American Indians and the late-eighteenth-century French Merveilleuses.

Her lack of training allowed her to be unrestrained in her design and unpredictable in her fabrics, mixing tartan, mohair, muslin, rubber and terry towelling, embellishing with safety pins, swastikas and razorblades. Her influences were always eclectic. When she met Keith Haring in New York, his naïve puzzle like compositions became knitted hieroglyphs in her ‘Witches’ collection for Autumn/Winter 1983. Seeing a production of the ballet Petrushka, she reinvented the crinoline, condensing its proportions, for ‘Mini-Crini’, the Spring/Summer collection of 1985.

In 1990, she opened a boutique called Vivienne Westwood in London’s Mayfair. The collections of the early 1990s are full of romance and eroticism, informed by her self-taught understanding of art history and classical tailoring. At the Wallace Collection – her favourite museum – she studied Watteau, Fragonard and French rococo art, translating it into bust-spilling painted corsets and pompadour-haired Parisian coquettes. But England too, had a place in her imagination with the ‘Anglomania’ show of 1993 in which a tartan kilted Naomi Campbell memorably toppled off her purple platforms.

The year after, she sent the model Carla Bruni down the runway in nothing but a fake fur coat and a fake fur G-string. The Daily Mail announced ‘Vivienne Westwood dragged haute couture to a new low in Paris yesterday’. But the collection, called ‘On Liberty’, was named for the 1859 essay by radical political philosopher John Stuart Mill. Liberty is the word we should associate with her. Politics mattered to Westwood, from her early seditionary days supporting sexual freedom, to her commitments to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and climate change action. She once dressed up as Margaret Thatcher for the cover of Tatler, but she was a vocal supporter of the Green Party. When she collected her OBE from the queen in 1992, she gleefully told reporters that she wasn’t wearing any knickers. She’ll be remembered for the freedom of her fashion, making clothes as romantic, sexy and subversive as she was.