Returning again and again to an archival photograph, the Khazakh artist has deployed modest means to write women, as well as others marginalised by patriarchal regimes, into history

In the early 2000s, Saule Suleimenova was browsing a book of archival photographs of Kazakhs compiled by scholar Alkey Margulan. One picture, dating to the pre-Soviet era, shows three brides in traditional attire betraying little emotion about this pivotal moment in their lives. The women stare at the camera, but for Suleimenova, it was as though they were looking directly at her. “The image was a portal, a channel,” the Kazakh artist told me when we spoke in June. “I had the feeling that these girls are also me, my mother, my grandmothers, my ancestors, my daughters, and my future granddaughters.”

Suleimenova has recreated this photograph many times over the last two decades, with each successive version marking a new stage in her practice. The artist first captured the figures in 2002 using grattography, a technique in which she coats a sheet of paper with paint, covers it with hot wax, paints other colours on the surface, then engraves with knives and sticks. After 2008, as she started to paint on top of her photographs of contemporary urban spaces, the three brides hovered over bulletin boards and concrete walls streaked with graffiti: ancestral spirits (or aruakhs in Kazakh) keeping a watchful eye over everyday life. From 2014, when Suleimenova began making collages out of salvaged plastic bags – an ingenious, laborious process of cutting and fusing cellophane with silicone glue – the brides’ headdresses and garments hosted logos and modern colours. Created with the help of volunteers, one bride floated like a canopy above the streets of Almaty for the 2015 ARTBAT Fest (Kelin, 2015).

When it comes to historical photographs of Kazakhs, Suleimenova observes, “the names of adult men are usually noted, but for women and children, only their region or aul would be written”. The artist searches the State Archives of the East Kazakhstan Region, the Smithsonian Institution website, and other places for these unknown people marginalised by patriarchal histories. The children and families featured in her series Kazakh Chronicle (2004 – ongoing) could not be further away from Bogenbay Batyr and other historic Kazakh warriors monumentalised in the post-Soviet era. Suleimenova characterises these monuments as a “lie”: mythmaking sanctioned by the young independent state. “I’m trying to find a realistic way to show true Kazakhness. For me, it’s a decolonial practice.”

Suleimenova’s ‘way’ is also modest, empathetic and at times satirical. The series No Cultural Value (2014) reflects on a common status that contemporary Kazakh artworks receive when exported abroad: in order to leave the country, they are stamped as having ‘no cultural value’. The insult extends, at least in Suleimenova’s case, to the archival photographs she recreates for the series. To stress the absurdity of this situation, she paints the people from these photographs over Photoshop collages of various bureaucratic documents she has been issued in her life – including the export stamps. In effect, she pre-empts the Kazakh state’s devaluation of her art by devaluing it herself.

One work in No Cultural Value shows Suleimenova’s own grandmother Mariam with two friends, all of whom were held at ALZHIR – a camp for wives of traitors to the Soviet Union – during Stalin’s repressions in the 1940s. Bimash, the ‘traitor’ in question, was at that point serving 15 years in the KarLag labour camp due to his statistical research into victims of the Asharshylyk. (We now know that this famine, brought on by the sedentarisation and collectivisation of nomadic Kazakhs, took approximately 1.5 million lives from 1930 to 1933.) During her time at ALZHIR, Mariam gave birth to Suleimenova’s father Timur; upon release, they lived near KarLag alongside other families with husbands at the camp.

In Suleimenova’s take on this photograph of Mariam and her friends, documents lurk in the background. The text of the export stamp hovers above their heads like a threat. “Authoritarianism,” she remarks, “is when a piece of paper is more valuable than human life or art.” The original photograph dates to the late 1920s making it both poignant and painful to acknowledge: the women have no idea what history has in store for them. Like the brides, they open portals in Suleimenova’s practice, and she has visited them many times.

Since 2018, Suleimenova has been at work on Residual Memory, a series that explores how “a common history is also a family history”: the trauma of colonisation and the struggle for self-determination are both felt within and across generations. The artist begins with archival images – including the one of Mariam – then recreates them using plastic bags often obtained from friends and colleagues. Echoing her former painting practice, she layers this material to achieve subtle shifts of colour, light and shadow. Plastic bags, which choke the steppe and terraform our oceans, may seem to cheapen the subjects at hand, but Suleimenova draws an unsettling link between them. “We prefer not to remember something traumatic,” she reflects. “We’d prefer to throw it away, but like plastic, it remains.” Even when subjected to state censorship or historical revisionism, some trace will always persist.

Suleimenova collected parts of Residual Memory into a small book published earlier this year, which concludes with a piece about the 1986 uprising. Protesting the replacement of an ethnic Kazakh party leader with a Russian stooge, tens of thousands took to the streets of Almaty and beyond. Teenage Suleimenova, defying her mother’s wishes, joined to read her poetry about Kazakh endurance, link arms with fellow demonstrators and shout ‘Viva Kazakh!’ Though eventually suppressed by KGB security troops and police, the uprising was one of the first in a wave of resistance movements across the republics that helped bring an end to the Soviet Union. The particular events in Almaty, which largely occurred at what was then called Brezhnev (now Republic) Square, seemed to presage the recent social unrest that Suleimenova has begun documenting in her work.

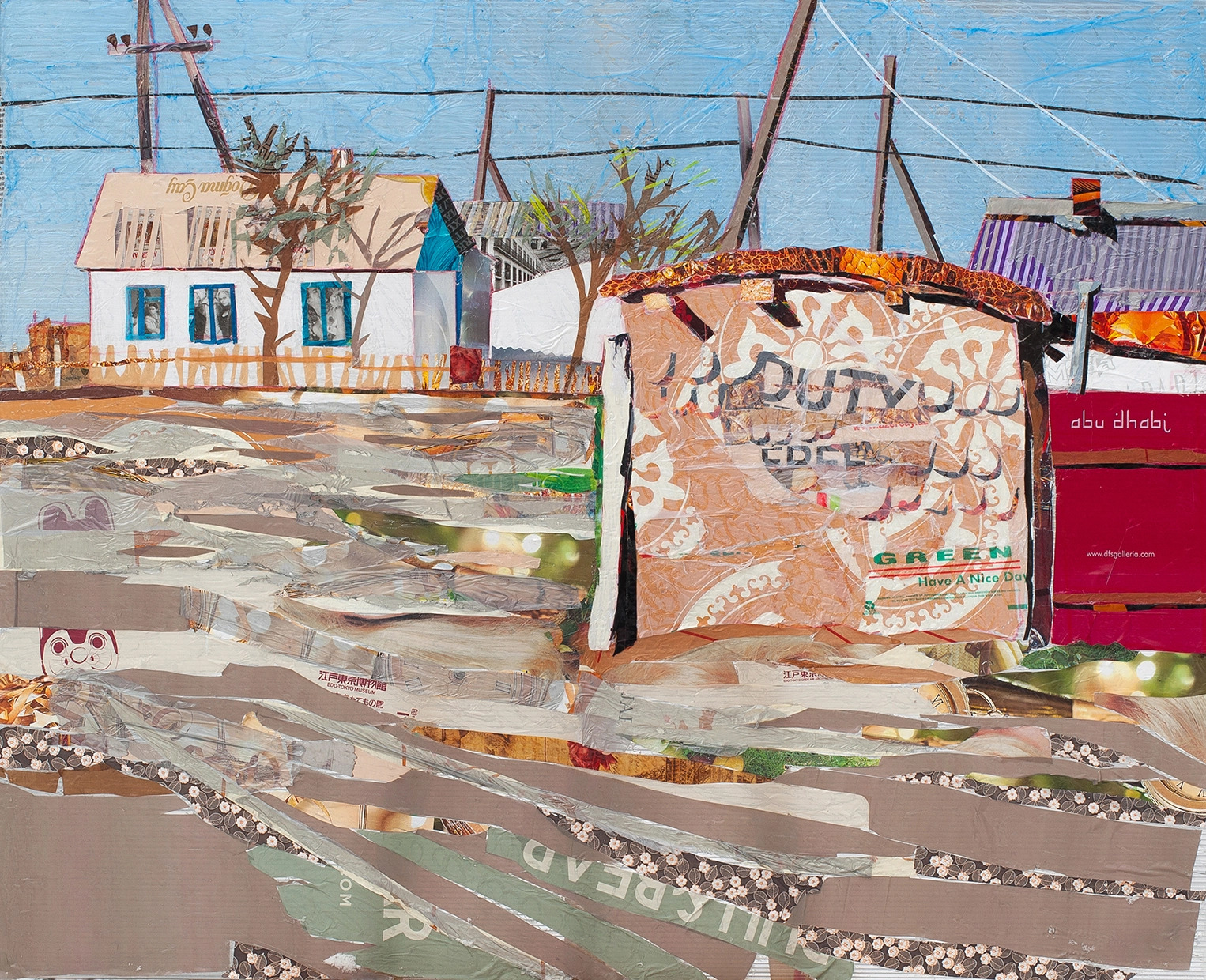

Following the 2019 resignation of Kazakhstan’s first president Nursultan Nazarbayev, Suleimenova recalls, “everyday there was something important that happened”: an oil worker’s strike in Aktau, the renaming of the capital from Nur-sultan to Astana, the arrest of journalist Svetlana Glushkova, a proposed referendum by the incoming president to build a nuclear power plant near Lake Balkhash. With Plastic Diary of Changes (2019), Suleimenova adapted her slow, demanding cellophane technique to meet the moment. “I didn’t have time to analyse or choose,” she says. “I was trying to work impressionistically: one day, one piece.” The results, which capture these incidents as well as everyday scenes from her surroundings, have the urgency of journalism and the intimacy of an artist’s touch.

Suleimenova soon expanded this ‘socially oriented’ way of working. In the large cellophane triptych One Steppe Forward (2019), demonstrators from Hong Kong, Ukraine, Turkey, France, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russia and elsewhere gather on one of three polyethylene sheets. The words ‘FOREVER’ and ‘AGAIN’ emerge from sweeping landscapes on the other two. Artist Almagul Menlibayeva has described how the steppe ‘is such a big and empty space; it forces a dialogue on you’. Its capaciousness allows for assembly, which to Suleimenova is the first step in building solidarity and practicing civic activism.

In January 2022, a protest in the town of Zhanaozen against rising fuel prices quickly grew in scale and scope. Thousands came together in Almaty’s Republic Square, scholar Diana T. Kudaibergen writes in her book The Kazakh Spring (2024), to demand ‘political changes, the resignation of the government, the return of the democratic constitution, and the improvement of economic conditions’. Kazakh state security forces and CTSO (Collective Security Treaty Organization) troops – most of whom Russia sent – were ordered by President Tokayev to suppress these ‘terrorists’ and ‘shoot without warning’. Suleimenova’s cellophane Tuman. Qandy Qantar (2023), based on a photograph from this time, shows demonstrators holding a banner stating, ‘We are NOT terrorists, we are ordinary people!!!’ Set in silhouette on a foggy winter’s day, they could stand in for any of us. According to the artist, this picture was taken just moments before the forces began shooting.

These days, Republic Square has few traces of the events of Bloody January. On the slope beside the restored City Government Building is a memorial hastily erected by the president – a bid to control the narrative. As visitors ascend, squat steles of black slate and granite give way to slender, white marble slabs. Their surfaces present quotes by Kazakh luminaries: meditations on fear and death mark the darker ones, and exhortations about national unity grace the lighter. No mention is made of the hundreds who lost their lives in the fray, or of those since detained, arrested and tortured.

One of the demonstrators in One Steppe Forward holds up a mirror, capturing the security forces lurking just beyond the edge of the work. In the face of state repression and obfuscation, Suleimenova believes she has a similar role to play. “My name Saule”, she observes, “means a beam of sun that we can see reflected in water. So I’m nothing. I’m just a mirror. I need to polish my soul to reflect this world in all its beauty and pain. If I don’t, the life goes out of me.”

Tyler Coburn is an artist, writer and teacher based in New York

From the Winter 2024 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.