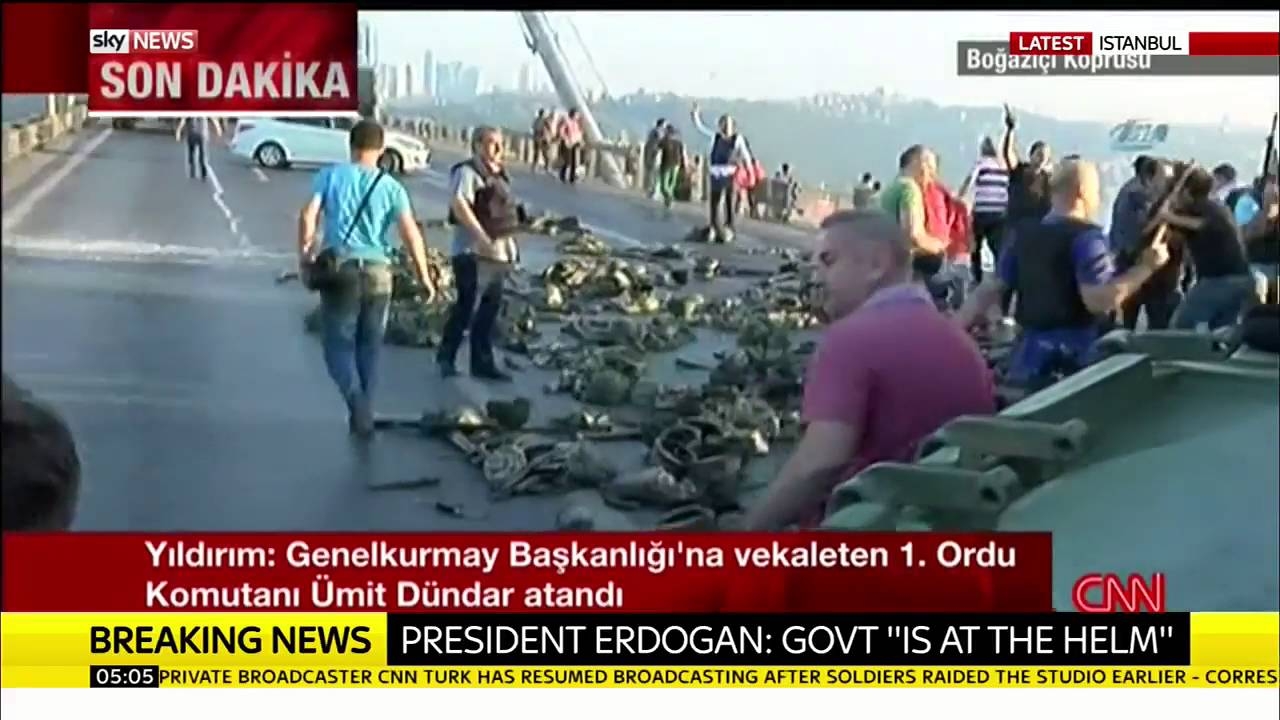

Watching atrocities unfold. Clicking the mouse, refreshing the browser, turning the newspaper page, tuning in. A friend’s family lives in Nice. I send a text: ‘Hope you’re OK…’ A reassuring reply: no family or loved ones caught up in the 14 July attack on the city’s Bastille Day celebrations. Back to passive observation. A few hours later I scroll as social media and rolling blogs report the ominous events of Istanbul and Ankara. Picture editors hurrying to replace images of the body-strewn French Riviera with tanks on the bridge over the Bosporus. This is how most experience the horrors of life.

Over the coming weeks, more images of shootings, rampages and attacks move those of Nice and Turkey down the news agenda. The McDonald’s in Munich, the clinic in Berlin, the protests in Dallas and Baton Rouge, the care home in Sagamihara, the nightclubs of Orlando and Fort Myers, throughout Syria, in Yemen, the Chad Basin, Burundi. Come the slaying of the priest in Normandy, it all seems terribly familiar. Scenes of horror available at any given moment, a ghastly Hobbesian ‘war of every man against every man’ to scroll and flick through at any moment we choose. Very real for those present, a mediated horror for the rest.

A ghastly Hobbesian ‘war of every man against every man’ to scroll and flick through at any moment we choose

It is difficult to think how art could react to this landscape of violence, particularly in this era of its unceasing mediation. The historian Walter Laqueur notes that ‘the success of a terrorist operation depends almost entirely on the amount of publicity it receives’. If ‘art’ is synonymous with ‘image-making’ or as a means of communication through signs and symbols, then these conflict events, arguably committed with a view to their mass-media proliferation and symbolic agendas, could be regarded as artistic acts in themselves (as sickening as that might sound). The perpetrators of these atrocities are self-aware, less in the business of conflict for militaristic cause, and more in the business of utilising violence as a means of creating ‘terror images’ for the media and for our consumption. The German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was much maligned when he referred to 9/11 as ‘the greatest work of art imaginable’, but his point, made perhaps too glibly so soon after the event, was that it would be the image of the Twin Tower attacks (the ‘incandescent image’ as Baudrillard termed it) that would linger longest in the collective memory.

Without wishing to oversimplify an event of great social, political and psychological complexity, one can only assume that Adel Kermiche, who made Father Jacques Hamel kneel before cutting his throat, would be aware of the symbolism of such an image, even if no cameras were there to capture it. Likewise, the commanders of the Turkish coup were surely thinking of the news cameras as much as military strategy when they ordered two tanks to occupy the Bosporous Bridge (and the protester who lay down in front of them might have done so with the iconographyof Tiananmen Square in mind). Terror images beget terror images.

Terror images beget terror images

Xanadu (2006), a four-screen installation by Robert Boyd currently on show in the group exhibition The New Human at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, can be read as a reaction to the temperament of conflict post 9/11 in its hyperaestheticisation of violence. As the video on one screen displays George W. Bush’s first State of the Union address following the New York and Washington, DC attacks (“Let’s roll”), a mirror ball attached to the gallery ceiling starts to spin. The Olivia Newton-John disco track after which Boyd’s work is titled kicks in and the viewer is subjected to a torrent of intercut projected images of war, murder and genocide from throughout the twentieth and early-twentyfirst centuries. Incited crowds riot, shots are fired, bodies tied to the back of Toyota pickups are dragged through the streets, corpses pile up, cities shake, buildings are burnt. When I first saw the work, I remember leaving the gallery feeling numb. Yet increasingly, as I read the news, I feel like I’m back there, trapped in that terrifying artwork as the horrors of the world pass interminably over the computer screen.

This article orirignally appeared in the September 2016 issue of ArtReview