Tunga’s 1974 debut exhibition, Museu da Masturbação Infantil (Museum of Childhood Masturbation), at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, gathered five series of drawings with titles such as O Perverso (The Pervert) or Pensamentos (Thoughts), which set out the sharp, provocative tone he would employ throughout his career. Exploring multilayered and often emblematic subjects, the artist scrutinises the poetics of desire, seduction, enigma and ritual. Indeed, he consistently refers to his practice – which spans sculpture, installation, performance, photography, video and drawing – as poetry rather than art. ‘I place myself in the poet’s role,’ he says, ‘because I think that poetry is not only something written, spoken or sung. I refer to what is behind poetry, and that’s text in any shape, in any language.’

Born Antônio José de Barros de Carvalho e Melo Mourão in the northeastern city of Palmares in 1952, Tunga is the son of notorious writer, poet and journalist Gerardo Melo Mourão and a social-activist mother. The family was forced into exile in Chile by Brazil’s military dictatorship, and it was not until the early 1970s that Tunga returned to Rio de Janeiro to pursue a degree in architecture while developing his artistic practice. Since then, the artist – a gentle, well- mannered man who still lives in the urban rainforest of Rio – has gone on to exhibit worldwide, having participated in the Venice (1982, 95) and São Paulo (1981, 87, 94, 98) biennials and Documenta (1997), as well as numerous solo shows.

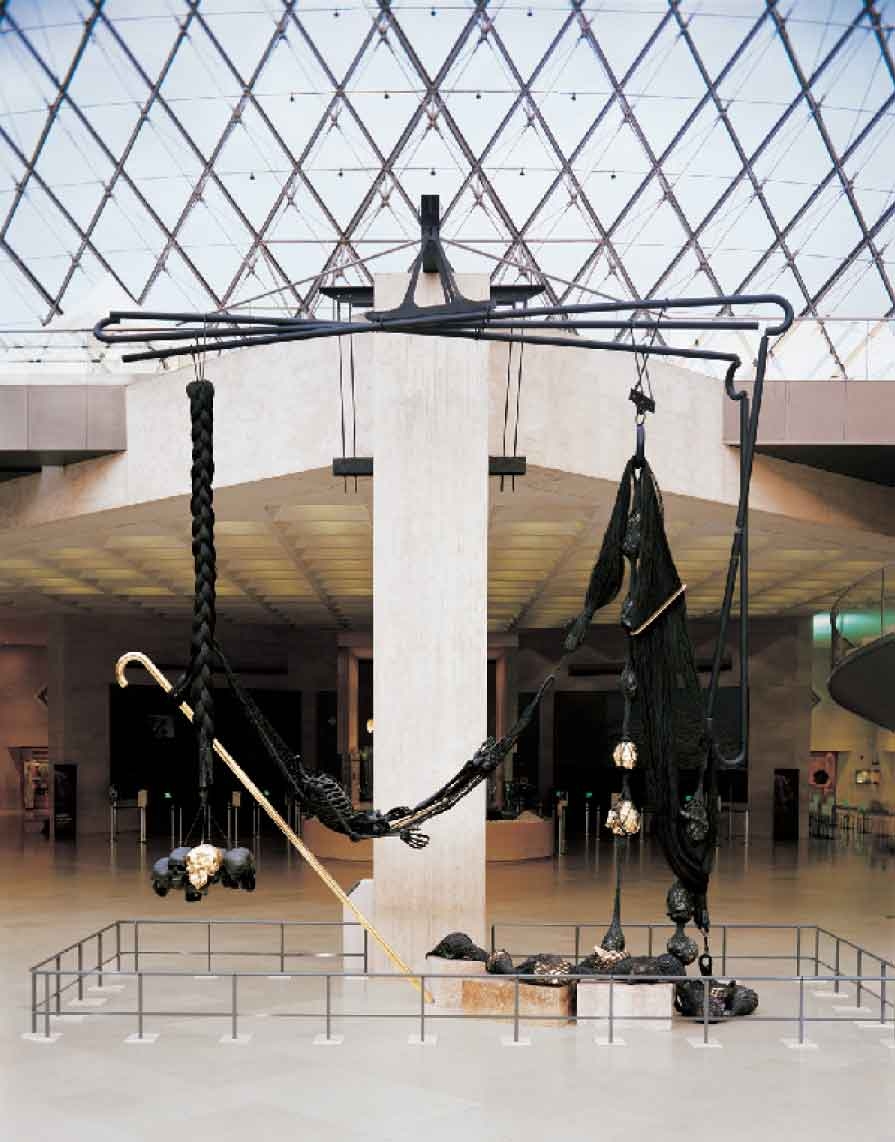

Tunga has constantly sought to provoke and to challenge the viewer. With À la Lumière des Deux Mondes (At the Light of Both Worlds, 2005), a site-specific work created for the Louvre’s glass pyramid – the first time a contemporary artist had exhibited in the institution – Tunga used one of the building’s columns as a pivot on which various symbolically charged objects were balanced: gold and black skulls and a giant walking stick intertwined with braided hair on one side; a chain of skulls caught in a dark net falling towards a floor littered with golden and black reproductions of heads from the Louvre’s classical sculptures on the other. Uniting the two poles was a headless skeleton lying in a hammock. Recently the artist has been developing a new series of large- scale untitled sculptures in which magnets fix a diverse range of objects – such as crystals or bottles – to a dark, rectangular doorlike structure. This new series brings together elements from two earlier bodies of work that explore similar materials and symbols: the ominous iron blocks in the artist’s various Lezart (1989) sculptures, and the magnets, also used in Lezart as well as in the later, smaller, more delicate run of assemblages titled Lúcido Nigredo (1999). All in all, this new series furthers the restless strategy that Tunga has deployed since his first exhibition: to bring together different elements in a work so that they might be charged with new values.

This article originally appeared in the September 2012 issue