Brick, stone, asphalt, gravel; wood, steel, copper, glass; 446,818,460 tons of concrete, 74,110 tons of plastic; 11,822,000 fragile bodies, 11,822,000 souls. Some of the ingredients that make up the city of São Paulo, according – with the exception of the human beings – to statistics listed in an installation by the Spanish artist Lara Almarcegui at the 2006 São Paulo Bienal (Construction Materials, City of São Paulo, 2006). How those elements come together to create the urban landscape, where they belong and what happens when they clash are some of the problems addressed in the recent work of a number of artists living and working in Brazil. They look past the monumental and the utopic to reveal the joins, the hard labour, the human error and the human cost beneath the polished facade of modern architecture and of the cities we live in – and of Brazilian Modernism, with its promise of ‘a singular and utopian future’, in the words of the Brazilian curator Moacir dos Anjos, ‘which we now know will never come’.

In art, the drama of clashing urban forces reverberates in works that address architecture’s monumentalism

In Brazil, the urban struggle is played out in the public–private axis: in local planning policy and in the dubious influence wielded by powerful construction companies, whose bottom-line requirements are the basis of the kind of blunt, blocky, hard-to-live-inside urbanism that shapes many a city in the Latin American country. It takes place on the peripheries of every major city and in some cases inside them, in the form of favelas and mass land occupations. It’s at the heart of the dozens of major building occupations that have sprung up in downtown São Paulo in the past year, in a current emerging from the Landless Workers’ Movement and socialist political groups of the 1980s and 90s, and in some cases spurred by artist collectives. The latter include Casa Amarela, a beautiful abandoned mansion on Rua da Consolação that was occupied in February and is run as a shared workshop, art and performance space; and Ouvidor 63, a 13-storey building downtown that was broken into and squatted by a collective of musicians and artists in May.

The struggle is discernible more viscerally, in flesh, blood and broken bones, and in the lives lost in the eternal imperative to construct. It’s there in the hastily erected flyover, part of the new infrastructure accompanying the renovated World Cup stadium in Belo Horizonte, that suddenly collapsed midway through the tournament, killing two drivers and injuring 22 people. And it’s there in the eight workers killed in onsite accidents during the construction of the World Cup stadiums.

In art, the drama of clashing urban forces reverberates in works that address architecture’s monumentalism and apparent neutrality, peeling it back to ask questions about how cities are made and how they are sustained; about who does the work, who reaps the profit and who pays the price. It resonates in the work of the contemporary art collective Bijari, in its urban interventions and happenings – in its viral Gentrificado poster (2007), for example, which pasted the word ‘Gentrified’ onto the walls of dozens of occupied buildings in downtown São Paulo, or projected it onto their facades. It’s in Clara Ianni’s Black Flag (2010), also in São Paulo, in which she draped a black flag, a symbol of death and mourning, over the entrance to a beautiful antique building in the city centre that had remained empty except for sporadic use for many years, questioning the vast number of disused buildings in the city. It’s in the work of Marcelo Cidade and André Komatsu, in their 2011 collaborative show, The Natural Order of Things, in which breezeblocks mass on tiny wheels, haphazardly, around a wordless street sign and the debris of a strange building site, including neat heaps of sand and sugar, coffee and soil.

It’s difficult to think about architecture in Brazil without the figure of Oscar Niemeyer instantly looming large

And it’s there, large as life, in the work of the Mexican artist Héctor Zamora, who lives in São Paulo. In Inconstância Material (Material Inconstancy, 2012), Zamora brought a crew of construction workers into São Paulo’s Luciana Brito Galeria to perform a kind of bricklayers’ ballet, in which they tossed hundreds of clay bricks from hand to hand along a human chain, as is done every day on building sites. Calling out a random selection of words and phrases from ‘Gigante’ (‘Giant’, 2012), a poem created for the artwork by the artist Nuno Ramos, the men worked in a spectacle of speed, dexterity, human error and dust, missed bricks smashing to the ground as others piled up to form hurried, impro vised structures. “I wanted the piece to leave my hands, and to let them take control of the work,” says Zamora. Having the words to call out to one another as they heaved the bricks between them helped the builders relax in the unusual environment of the gallery, he says, adding a playfulness that gave rise to organically emerging songs, chants and words, until Ramos’s words began to melt into the improvised babel. “The bricklayers became the protagonists, the stars of the show,” says Zamora. “The work was a way to create a circuit in which they were visible, recognised, laughing as the bricks flew between them – it was a way to break the myth of architecture as untouchable.”

It’s difficult to even think about architecture in Brazil without the figure of Oscar Niemeyer, and the modernist moment he epitomises, instantly looming large. The architect, who died in 2012, was one of the prime movers in the creation of Brazil’s urban landscape, most famously in the form of Brasília, a futuristic delirium and the country’s capital city, designed in conjunction with Lúcio Costa and con structed from scratch on the vast savannah in just five years (1955–60). An exhibition held from June to July at Itaú Cultural, a major institution on São Paulo’s Avenida Paulista, paid homage to Niemeyer’s unique, lyrical genius. In Oscar Niemeyer: Clássicos e Inéditos, a 16- metre-long roll of paper bears sketch after elegant sketch of the asto nishing buildings that form his legacy, which he drew as he spoke during the filming of Oscar Niemeyer: O Filho das Estrelas (Son of the Stars), a 2001 documentary about his life and work. The film was also on display at the exhibition, along with more drawings, a handful of scale models and 51 sets of plans for projects that never left the drawing board.

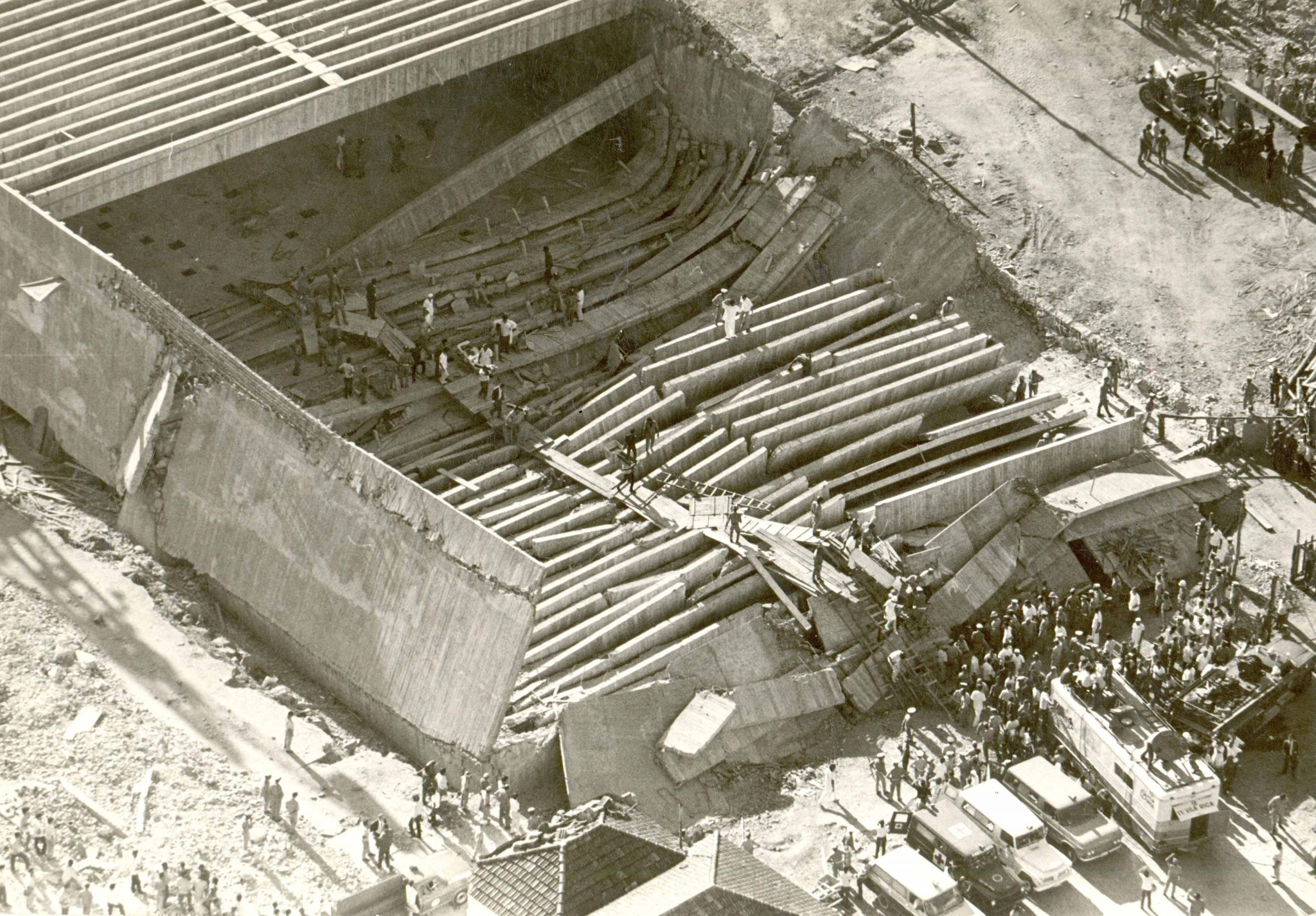

In a simultaneous exhibition at Pivô, a not-for-profit gallery down the hill in São Paulo’s Centro, the artist Lais Myrrha has spent the past year working on another project in which Niemeyer’s work looms large, to very different effect. Opening two days after the Itaú show, Myrrha’s Projeto Gameleira 1971 (2014) takes as its point of departure the story of Brazil’s worst civil-engineering disaster, in which a monumental building designed by Niemeyer, destined to become part of a cultural complex in Gameleira, a district in Myrrha’s home city of Belo Horizonte, collapsed while still under construction, killing more than 100 construction workers with the implacable force of 10,000 tons of concrete. According to press reports and contemporary accounts, the governor of the state of Minas Gerais, Israel Pinheiro, was keen that the complex be inaugurated during his soon-to-end term in office, and the work was proceeding at an accelerated pace.

The accident, which took place during the military dictatorship, was rapidly forgotten and is almost completely unknown in Brazil today

Myrrha’s installation takes the form of an immense, reimagined architectural model of the crumpled construction site, based on one of the few photographs available of the scene of the disaster. Visitors are confronted with the horrible geometry of the fallen concrete beams, realistically rendered in painted plasterboard on wooden frames, and invited to walk across the model via a stretch of scaffolding placed over the top of it, staring into a clatter of fallen slabs, absorbing the scale of the catastrophe with an almost physical pang.

Leaving the model, visitors are faced with a wall lettered with the names of the 117 workers known to have perished, a component of Projeto Gameleira 1971 titled In Memory of the Silence of the Architect. The title refers to the fact that Niemeyer never publicly spoke of the disaster, not even to defend the project’s engineer, Joaquim Cardozo, who took the brunt of the blame. It relates too, obliquely, to the scandalous, not unrelated fact that the accident, which took place in 1971, during the military dictatorship, was rapidly forgotten by the population at large, and is almost completely unknown in Brazil today, except in architectural faculties, and in the homes and hearts of those directly affected.

“The accident stayed in the media for a month or so,” Myrrha says. “Particularly in Minas Gerais; but then it more or less disappeared. It doesn’t appear in Niemeyer’s biography, not even as a footnote.” Indeed, despite the best efforts of more than one doctoral research student, the blueprints for the project are also apparently nowhere to be found. Disappeared like the rubble of the disaster, gathered up and disposed of, the project quietly aborted. The Expominas convention centre, scene of Belo Horizonte’s World Cup FIFA Fan Fest, now stands on the site of the disaster.

The accident’s eradication from Brazilian history makes the tragedy, newly revealed by Myrrha’s artwork, feel like fresh, urgent news, materialising to break through the silence more than 40 years on. Myrrha has received emails from at least one member of the families of those who died at Gameleira, expressing gratitude to her for making the accident public again. But not everyone, apparently, feels the same way. In a statement published on the Institute of Brazilian Architects website, the Itaú Cultural exhibition curator, Lauro Cavalcanti, and its designer, Pedro Mendes da Rocha, launched a coldly fierce attack on Myrrha, accusing her of opportunism and of exploiting the dead to create her artwork.

What ends up being inscribed on our collective memory comes down again and again to power

In a response published on Pivô’s site, Myrrha writes that she has made no suggestion nor believes that blame for the accident lay either with Niemeyer, who was living in France at the time, or with Cardozo. “I find the architect’s lifelong silence about the disaster unpardonable,” she says. “Nevertheless, the work is not about Niemeyer per se. It’s about the way what ends up being inscribed on our collective memory comes down again and again to power.” It’s about silence, and about the devastating, unmarked absence of the people who lost their lives at Gameleira; and the chronic invisibility – the powerlessness – of all the people who build our cities from the ground up, with their hands.

Projeto Gameleira 1971 ‘seeks to undo social amnesia… regarding occurrences of undeniable importance,’ writes Moacir dos Anjos in the notes for the exhibition, ‘which in most cases involve the imposition of damages on individuals or groups who do not possess the material and symbolic means to make their losses a public fact’. The third and final element in Myrrha’s installation is a tall stack of posters bearing the photograph of the Gameleira collapse, set alongside the offset plate used to print them, fading slowly, inexorably as the exhibition wears on – the image on the delicate plate, according to the printer, lasts only a matter of months. But the stack of posters invites visitors to take one away with them when they go. “Taking a poster confers a certain responsibility to keep it,” says Myrrha, “maybe to display it and perhaps even” – the poster bears nothing but a photograph of the little-known historic scene – “to have to explain it to others. We, ourselves, are an archive.”

Myrrha is not alone in having engaged with elements of Niemeyer’s own history, and with that of the hundreds of thousands of workers who make his and other architects’ legacies manifest. Clara Ianni has frequently addressed questions of urbanism and of labour in her work. In the 2013 video Forma Livre (Brasília) (Free Form (Brasília), 2013), vintage images of Brasília phase in and out as Niemeyer is heard speaking in an interview made for the documentary Conterrâneos Velhos de Guerra (1991), about the so-called candangos, who came from all over Brazil to build the new city. Questioned during the interview about a massacre of striking workers that took place in Brasília in 1959, at the Pacheco Fernandes Dantas workers’ encampment, Niemeyer denies all knowledge of it, irritably and repeatedly. “I’ve never heard of it,” he says. “You can’t ask me about things I know nothing about.” But the massacre has been discussed extensively by the left, says the interviewer. “Ask me a generic question,” says the lifelong communist. “Ask if I’m in favour of strikes. I’m in favour of each and every strike.”

“Favelas are constructed by exactly the same people who have built the cities their communities surround,” says Héctor Zamora. “There’s nothing inherently inadequate about the informal architecture they use.”

The plight of the workers who executed Modernism’s utopian visions is also addressed in a site-specific work from 2010 by Clarissa Tossin. The Brazilian artist, who is based in Los Angeles, staged Monument to Sacolândia, materialising the memory of a favela inhabited by workers on the immense project to build Brasília. In contrast with the elegant palaces of government their labour was crystallising in concrete, the workers’ homes at the Sacolândia (‘Bagland’) shantytown were made of leftover cement bags, ripped open and hung to form paper-thin, almost notional walls. The site was flooded in 1959 to form Brasília’s Lake Paranoá; and it was on the lake that Tossin launched her Monument: a large-scale raft made from cement bags over wood and Styrofoam, with the brightly coloured bags tracing out the shape of the Palácio da Alvorada, the first government structure in the new city, inaugurated in 1958, and the official residence of every president since then. In Monument to Sacolândia, the palace gardens become the verdant backdrop to the cement-bag palace.

“Favelas are constructed by exactly the same people who have built the cities their communities surround,” says Héctor Zamora. “There’s nothing inherently inadequate about the informal architecture they use.” In a homage to the technology and skills existing on the periphery of cities in Latin America and beyond, Zamora grafted Paracaidista [Squatter] Av. Revolución 1608 bis (2004), an immense shantytown structure, onto the side of Mexico City’s sleek Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, swelling up from the street to cling to the museum like an immense rusty organic parasite. “Construction workers are the people who build the walls we live inside, who solve the problem of urbanism on a day-to-day basis,” says Zamora. “Yet they are always hidden, excluded from the circuit of urbanism and of architecture.”

Melting away invisibly once their work is done, the builders’ presence is erased by the spurious perfection of the buildings they create, their innards and origins concealed under slick, polished finishes. But the frayed edges, improvisation and brutal honesty of informal architecture, says Zamora, are just as worthy of our admiration. “Imperfection and human error are important aspects of creation. They’re in everything,” he says. “They symbolise the natural, the organic and the true, generating a poetics, an aesthetic. The progressivist, capitalist system likes to talk about progress as if everything must only go forward, infinitely climbing and rising, but it takes no account of the way things grow, curve, fall and follow natural cycles.”

Modernism, heavily involved in the circuit of progressivism, has been guilty of the same ideological omission, he says. “Everything about it responded to the linear narrative of progress, and of providing solutions to capital’s demands. Its ideals weren’t the absolute, unique truths they seemed to be at the time, and that’s why Modernism has been so compelling as a subject for reflection in Brazil. Human error has no place in the politics of progress,” he says, “but the truth is, that’s a lie.”

This article originally appeared in the September 2014 issue