MAXXI, Rome, 21 April – 4 September 2016

As the title suggests, this exhibition marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of Florentine Radical architecture practice Superstudio; on show is an overview that spans metaphysics, ecology, social critique and practice. The display, curated by Gabriele Mastrigli, was conceived alongside Superstudio’s founders, Adolfo Natalini and Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, and Gian Piero Frassinelli, who joined after the group’s formation in 1966. It was together with another influential Florentine design group, Archizoom Associati, that members of Superstudio (now grown to include brothers Roberto and Alessandro Magris, as well as Alessandro Poli) developed the term Superarchitettura (Superarchitecture), holding an exhibition of the same name in Pistoia (also in 1966). Both in design and architecture, the group pursued a practice that aimed at a critique of the dry functionality of modernist architecture since the Bauhaus. What Superstudio 50 high-lights is the extent to which Superstudio appears retrospectively to have foreseen – perhaps unwittingly, even – the nature of twenty-first-century living.

This is conveyed at the exhibition’s entrance via the display of architectural drawings from two series of works, entitled Macchina per Vacanze (Holiday Machine, 1967–8) and Il Monumento Continuo (The Continuous Monument, 1969). The former body of works, such as Una ‘macchina per vacanze’ a Tropea (Sulle bianche scogliere di Dover) (A ‘machine for holidays’ in Tropea (On the White Cliffs of Dover)), consists of drawn-upon photomontage featuring huge industrial constructions that augment the natural landscape. These vast and brutal hypothetical machines, designed to improve coastlines by controlling tides, point to the folly of humanity’s attempts to supplement the planet’s natural resources and rhythms.

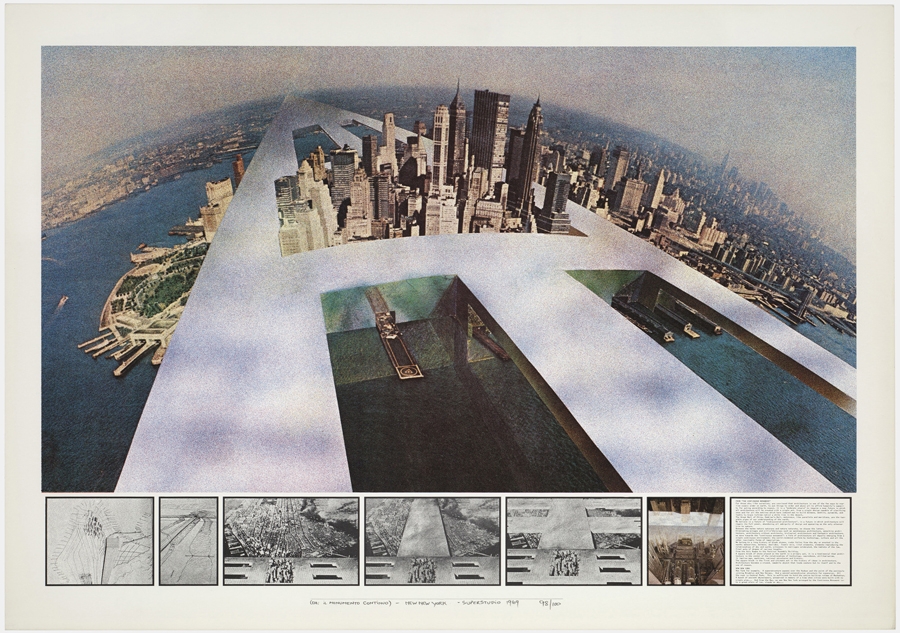

Similarly, the Il Monumento Continuo series hypothesises one seamless architectural structure that spans the world. This construction, devoid of ornamentation, appears in drawings and prints alongside historical monuments and town housing as both an idealised form of democratic architecture and a provocation aimed at modernist architecture’s preference for utility over formal qualities. Such an ability to critique modernist architecture and its tendency towards homogenisation while hinting at its positive potential can also be seen in the lithographic print Il Monumento Continuo: New New York (1969): the scenario features a sleek glass structure that appears to both engulf and frame New York City. Its undulating mirrored surfaces leave the viewer questioning whether such minimalist perfection would really complement both nature and the history of architecture, or whether its sheer formlessness would serve only to impose a slick manmade aesthetic upon the natural world.

The notion of a ‘continuous monument’ per se appears to hint at a level of global interconnection we take for granted in the era of the Internet. Similarly, the film Vita (Supersuperficie) (Life (Supersurface), 1972) envisages a world where we live alongside nature in nomadic encampments replete with power supplies attached to a vast grid spanning the landscape. Adjacent to the aforementioned film, the installation Microenvironment Supersuperficie (1971–2/2000) creates in mixed media a 1:1 model of such a grid, replete with power adaptors that look uncannily like the multisocket plug adaptors that we today find ourselves plugging our laptops, tablets or phones into at any given opportunity, whether in a bar, library, airport or indeed anywhere a plug socket might plausibly exist. We have never been so ‘connected’, though one might equally say we have never been so dependent. Superstudio 50 allows for reflection upon an important period in the recent history of architecture, yet its strength as a show resides in its ability to lead the viewer to reflect on the present, and where we go from here.

This article was first published in the September 2016 issue of ArtReview.