Shows around the Biennale – Oliver Beer’s Little Gods, Angela Su’s Arise, Human Brains at Fondazione Prada and Enchanted Modernity at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection – engage in philosophies of magic

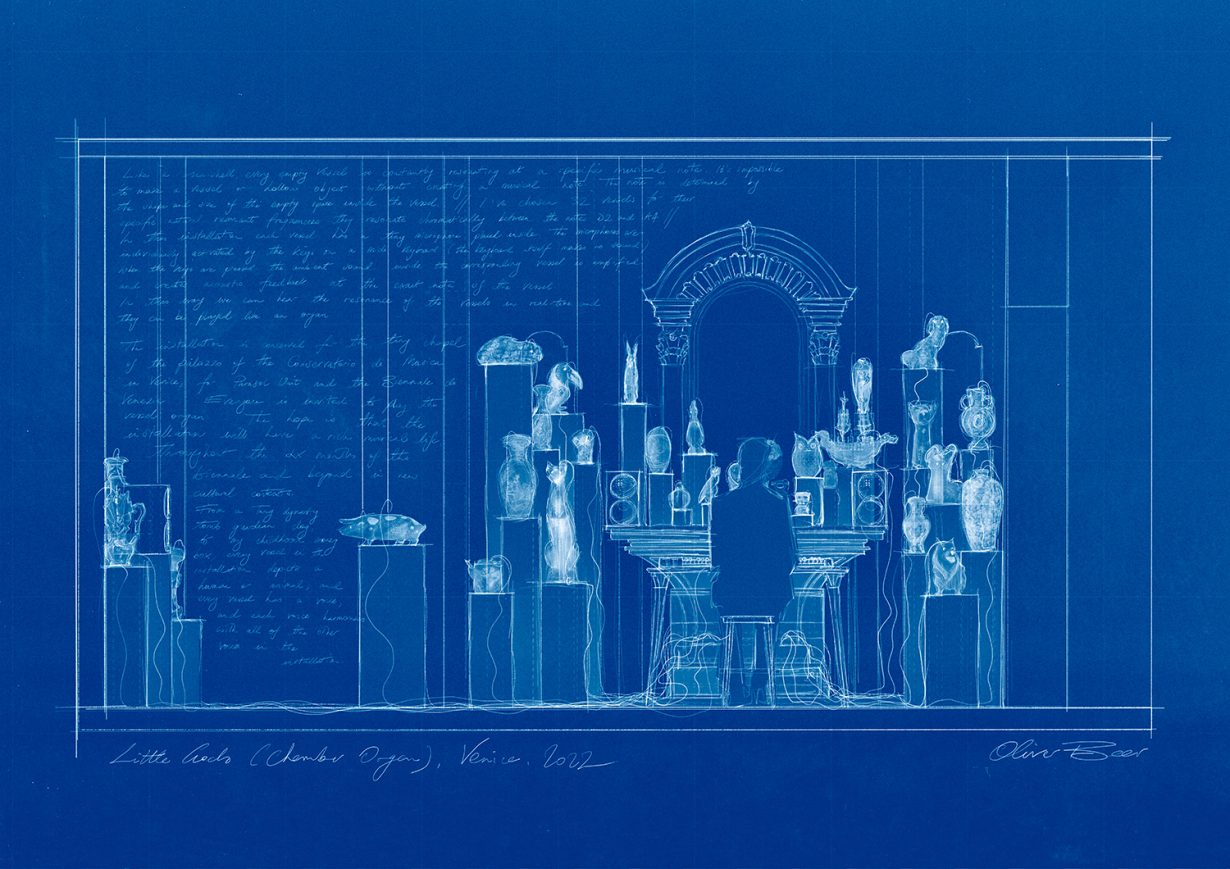

Late one night this week, I joined a small crowd at Venice’s Conservatorio Benedetto Marcello. Cocooned within the pint-sized chapel of the music school’s baroque palazzo is a strange scene. Here, the artist Oliver Beer has arranged an eccentric collection of vessels (including a money tin he’s had since childhood, in the shape of a squashed Beefeater) on plinths, microphone wires running from the insides of each to a keyboard, so that the pots can be ‘played’. All spaces have their resonant frequencies (including the room you are sitting in right now); when those frequencies are amplified (whether within a teapot, miniature pirate ship or ceramic dog), we can hear it too. When I visited his installation Little Gods (Chamber Organ) – part of the Parasol Unit group show Uncombed, Unforeseen, Unconstrained – Beer had just begun a marathon 24-hour performance, playing his own variations on Erik Satie’s 1893 Vexations (only a few lines long, the piece’s original score carries the added suggestion that its uneasy piano phrase be repeated 840 times, très lent). The humming toy-like tones bled through the space, forming a texture that floated into the adjoining galleries. In these singing pots, not only is sound a carrier of nostalgia and memory, there’s the idea that sound is something that might outlive us all.

61 x 85 cm. © Oliver Beer Courtesy of the Artist and Almine Rech

Little Gods shows us – in all its simplicity – the act of listening. It situates us within the sound of the space itself: an acoustic order ruled by the laws of our universe, not by human messiness. But Angela Su’s Arise, the Hong Kong pavilion at the Venice Biennale, grapples with our desire to upturn those rules of nature. In her installation, magical thinking becomes an allegory for the strange histories of countercultural politics and ritual transformation. It features Su’s delicate, skittering embroideries of black hair – which call to my mind the eldritch work of Mervyn Peake, all organ-shaped shadow and monstrous form. There’s the suggestion of an orifice, sac and tumour; a human embryo nestles within the unfurled wings of a bird of prey. These spiny, veiny pictures are the antecedents to a chamber spiked with acoustic foam that houses the faux-documentary The Magnificent Levitation Act of Lauren O (2022), a piece of speculative fiction whose protagonist – a member of a band of antiwar, vaudeville, anarchist activists called Laden Raven – succumbs to otherworldly forces. What is it about the dream of levitation that fascinates us, its narrator asks. ‘Freedom, the ecstasy of self-transcendence, or our impulse to rebel,’ she answers. Footage of aeronauts and swooning nuns, woven into a narrative that references the 1967 March on the Pentagon – in which some protesters spoke of their desire to levitate the building through collective will – pulsates in clashing montage. There’s a poignancy to the impossible dreams of shattered social movements, Su’s film suggests.

Human Brains: It Begins with an Idea at Fondazione Prada – part of a longterm multidisciplinary programme devoted to neuroscience and curated by Udo Kittelmann in collaboration with artist Taryn Simon – is a journey across the history of our attempts, both visual and literary, bizarre and morbid, to give form to the workings of the mind. This unfolds as a series of new short stories by 32 authors – narrated by George Guidall – set alongside illuminated vitrines filled with curiosities. One such case contains a 3D copy of a pair of Sumerian cylinders – a millennia-old cuneiform text – which is the earliest record of a dream (after which Gudea, ruler of the ancient city-state of Lagash, decides to build a new temple). The scrolls are accompanied by Salman Rushdie’s tale The Interpretation of Dreams (2022), a short parable of how we came to describe ‘the nightly unconsciousness’, and the bloody conflicts waged in the name of our differing interpretations of such nocturnal visions. A reading of Tilsa Otta’s The Circular Illuminations (2022) – a fable of messages from the gods and cosmic language that slices through the cranium – hovers above an Incan ceremonial knife; while writer and Oulipo member Hervé Le Tellier offers a playful counter-reading of Hieronymus Bosch’s 1494 Cutting the Stone, a painting in which a quack doctor carries out a trepanation to remove the ‘stone of madness’ from his patient’s brain (an image that became a popular trope across artworks of the period). The exhibition’s own collection of treasures approaches another image of art history, that of the Wunderkammer, from a wooden model of an anatomical theatre and a set of tiny busts for the study of phrenology to a freaky wax model of a carved-out head. These pairings of small antiques lit in glowing boxes with biblical, fantastical stories function like spells: incantations that command us to see beneath the surface of objects.

What happens when the artist plays the magician? Kurt Seligmann visualised this thought in his 1955 The Alchemy of Painting, in which the artist appears as a dark wizard, draped in hushed purples and crimsons, wand in hand. The painting is included in the magisterial exhibition Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection (in a joint endeavour with the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany, to which it will travel later this year) which offers an account of the art movement’s interests and enmeshment in the arcane and occult, from the protosurrealism of Giorgio de Chirico to the crazy bestiaries of Leonora Carrington. For so many of these artists, this alchemical thinking began with the pigment itself. You can see it in Seligmann’s malevolent, tornadolike forces, which he created by tracing over the patterns of fractured glass. Max Ernst’s devastating Europe After the Rain (1940-42) takes its pockmarked skinlike sheen from the use of decalcomania, in which glass is set over the freshly daubed canvas, creating a suction effect of air pockets and rivulets of paint. I can’t stop looking at Wolfgang Paalen’s Magnetic Storms (1938), in which the Austrian surrealist invoked the image of the mythical Wild Hunt, spectres riding across the night sky. Paalen did this by fumage: a technique in which he would expose the canvas to a burning candle, its smoke forming strange impressions on the surface, later painted over in oils.

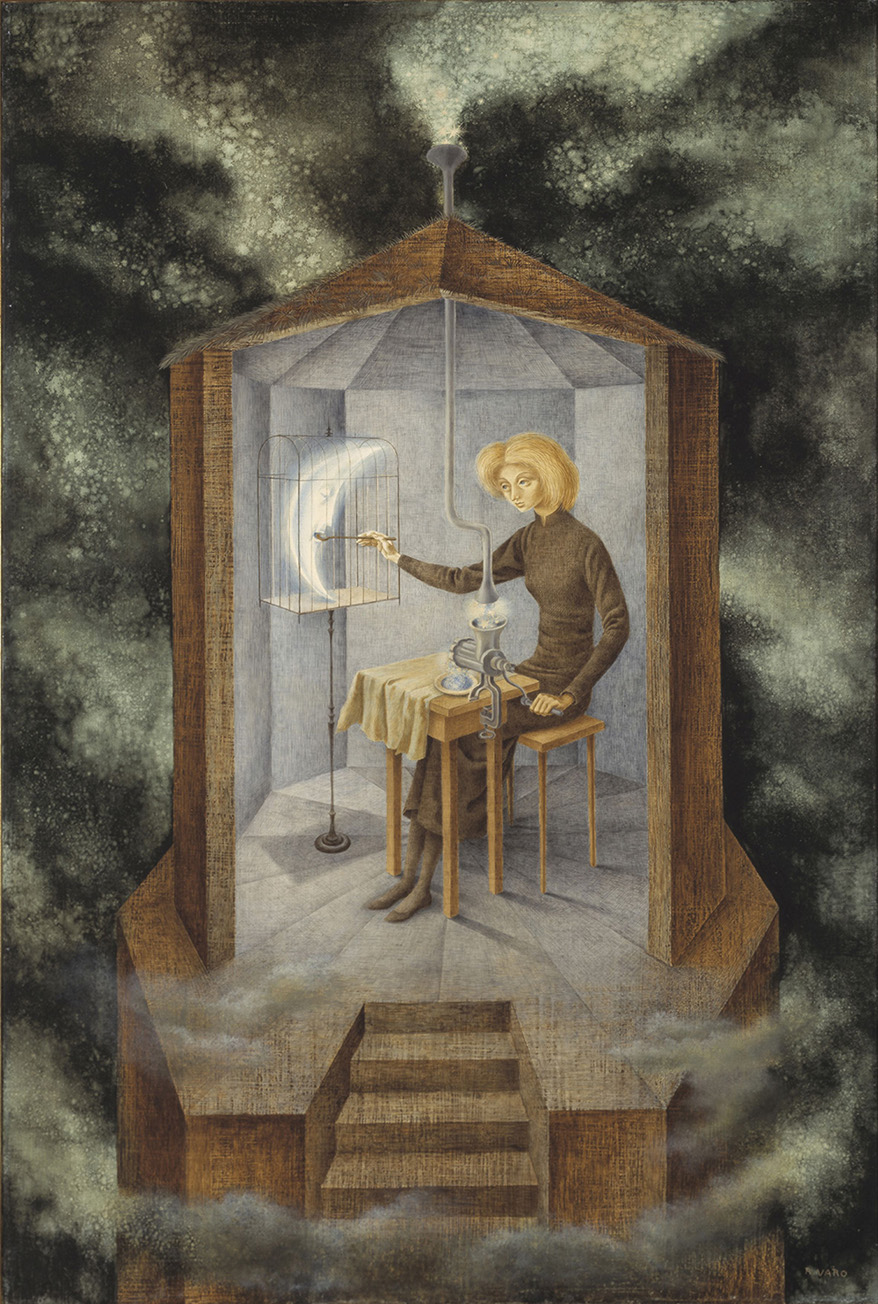

That’s how paint and pigment land. But Surrealism and Magic also offers different ideas of the occult as forms of knowledge. One is the knowledge held by the powers that be, perhaps represented in Óscar Domínguez’s tarot card featuring a moustachioed, mummified Freud as the Magus of Dreams (part of a deck produced by surrealist artists in 1940 within the zone libre of Marseille). Or Leonor Fini’s Portrait of the Princess Francesca Ruspoli (1944), in which the aristo cosplays as a beguiling witch. But there’s also the occult as a set of rebellious secrets – half-remembered memories of the old world carried into the new – passed down from generation to generation. Look at Carrington’s witches, who pursue their practices in brilliantly glowing chambers, rather than dank huts or dark woods. Or in Remedios Varo’s Celestial Pablum (1958), a woman feeds stardust to a caged moon. She toils away in a lonely turret; but she’s surrounded by sparkling clouds, their vapours drifting up the canvas, suggesting a vast, cosmic plane beyond.