In September I visited Goldsmiths CCA in South London. It was my first visit to an art venue since spring. A drumbeat was emanating from the building’s upper floors, thump after muffled thump. The sound grew louder as I stepped inside, pinging sharply around the galleries. After months of encountering sound through headphones or laptop speakers, that unruly reverb confirmed that, really, there’s no substitute for the physical impact of encountering art in the flesh. I remembered a line from Pascal Quignard’s epigrammatic and ironically titled The Hatred of Music (1996), in which the French writer observes that ‘to hear is to be touched from afar’.

I followed the sound of drumming to its source: a luminous, high-ceilinged room on the museum’s second floor. The pristine white walls were decorated with rectangular sound-dampening panels, also white, that brought to mind minimalist sculpture. In the far corner, the artist Appau Jnr Boakye-Yiadom was seated behind a drumkit. As he played the hi-hat, the cymbals’ harsh, high frequencies shivered in the upper reaches of the room. When he hit the kick, by contrast, the floorboards vibrated under the soles of my feet, making my shin bones hum like tuning forks. The artist tapped the snare with his drumstick: one, two, three, four. For Quignard, the physical vibrations of which rhythms are composed create an ‘involuntary intimacy between juxtaposed bodies’. One reason we listen to music in public is to feel part of something larger than ourselves, united with other bodies by our subordination to communal tempo. That process felt differently charged in the context of social distancing.

I pulled up the QR-coded exhibition guide on my phone. The premise of the piece, titled Before, During & After, read like an anxiety dream. Over the course of this autumn exhibition, Boakye-Yiadom was learning to play drums in public, every fluffed beat and dropped stick gazed at by strangers. The potential for embarrassment was heightened by the assumption that the works of art we encounter in galleries, whether we like or dislike them, will at least be finished. But open-endedness is key to this artist’s approach. In his sculptures, videos and sound installations, drums are remixed and repurposed. Recordings of live performances soundtrack later videos. Packed-away kits become table stands. Drums point to an interest in hybridity and cultural cross-pollination, an element central to tribal rituals, nightclubs, jazz breaks and historical battlefields. But this was the first time he’d played them himself.

Headphones on, a clear PPE visor over his face, Boakye-Yiadom’s gaze was fixed on a Hantarex monitor playing a prerecorded lesson by one of five invited drummers. He watched, waited, played. Paused. He shifted from snare to hi-hat and started again. As musical performances go, it wasn’t exactly Elvin Jones. Nor was it trying to be. By foregrounding the repetitions, failures and improvements essential to the unglamorous business of honing one’s musical chops, Boakye-Yiadom was really drawing attention to time and to the patterns we impose on it.

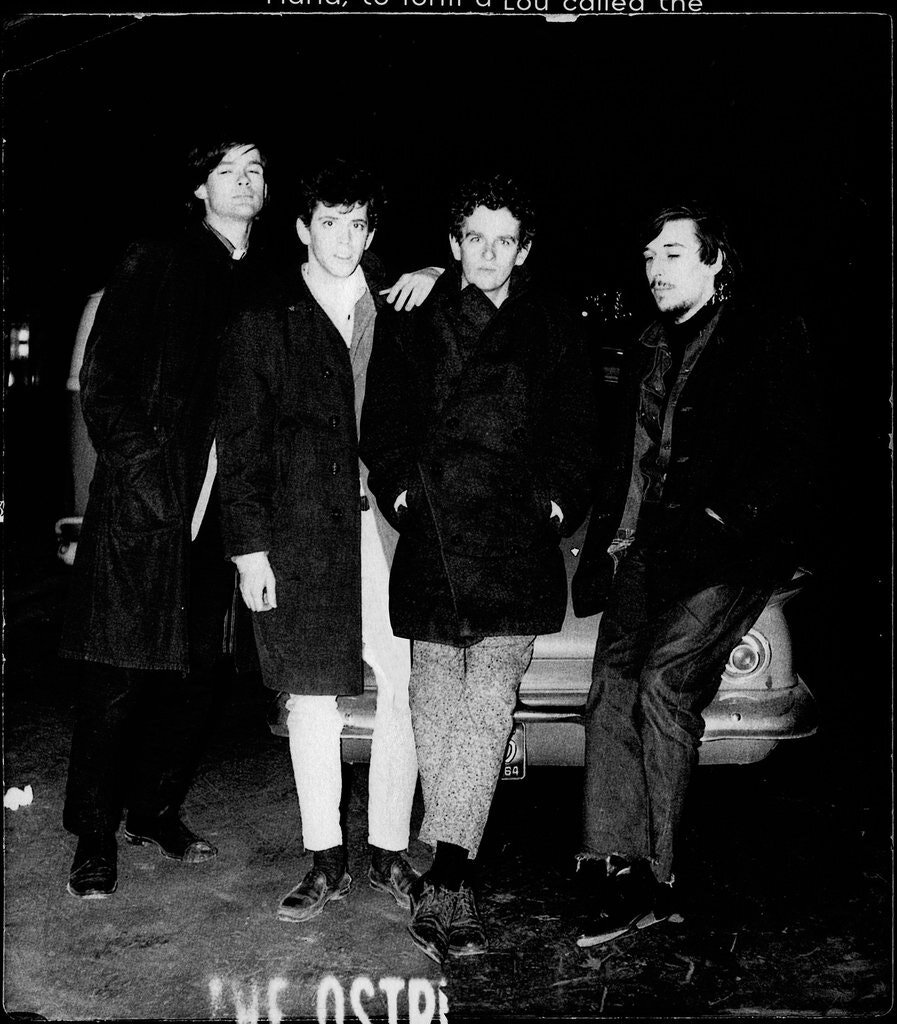

The only other artist-drummer I could think of was Walter De Maria. Active on the 1960s New York music scene, he was for a short time a member of an early incarnation of The Velvet Underground. During this time he recorded two plashy, improvised ‘drum compositions’ in which he overdubbed repetitive, jazz-inflected rhythms with field recordings: the chirping insects of Cricket Music (1964) and the thrashing waves of Ocean Music (1968). Incorporated into the soundtrack for his 1969 film Hardcore (and rereleased by Gagosian on a 2016 CD), these compositions coincided with De Maria’s pivot from objects to environments. Music was crucial to the evolution of what the artist called his ‘very clean, quiet, static, non-relational sculptures’ – such as his less-than-flattering Portrait of John Cage (1961), a punning work depicting the composer as a tall, narrow cage – to the Land art for which he is best known. In an accidental echo of De Maria’s interest in elemental sounds, heavy rain was falling – drumming – on the centre’s roof in a roaring accompaniment to Boakye- Yiadom’s stop-start beats.

A few days later I returned to the gallery. The drum kit had been packed away and stacked against the wall, except for the kick, which, like a sign in an absent shopkeeper’s window, read: ‘Here SOON’. But the artist was not entirely absent. On the Hantarex monitor was a video. Collaged from audio recordings of Boakye-Yiadom’s drum lessons and closeup footage of snares, hi-hats and kick drums, the piece was evolving over the course of the exhibition as the artist added to and reedited the footage. Where De Maria was torn between commitments to the stage and the gallery, and after Ocean Music abandoned drumming, Boakye-Yiadom identifies in such tensions raw material for art. In his 1991 essay ‘Sounds Authentic’, Paul Gilroy attributes to Quincy Jones the aperçu that ‘the times are always contained in the rhythm’. Drumbeats reflect the cultures from which they emerge just as potently as images do. And with lockdown uncertainty looming, baby-step rhythms felt apt.

Patrick Langley is a writer based in London and an editor at art-agenda