In Eclipse, a number of artworks play with the line between information revealed and meaning withheld, what can be decoded and what must remain unknowable

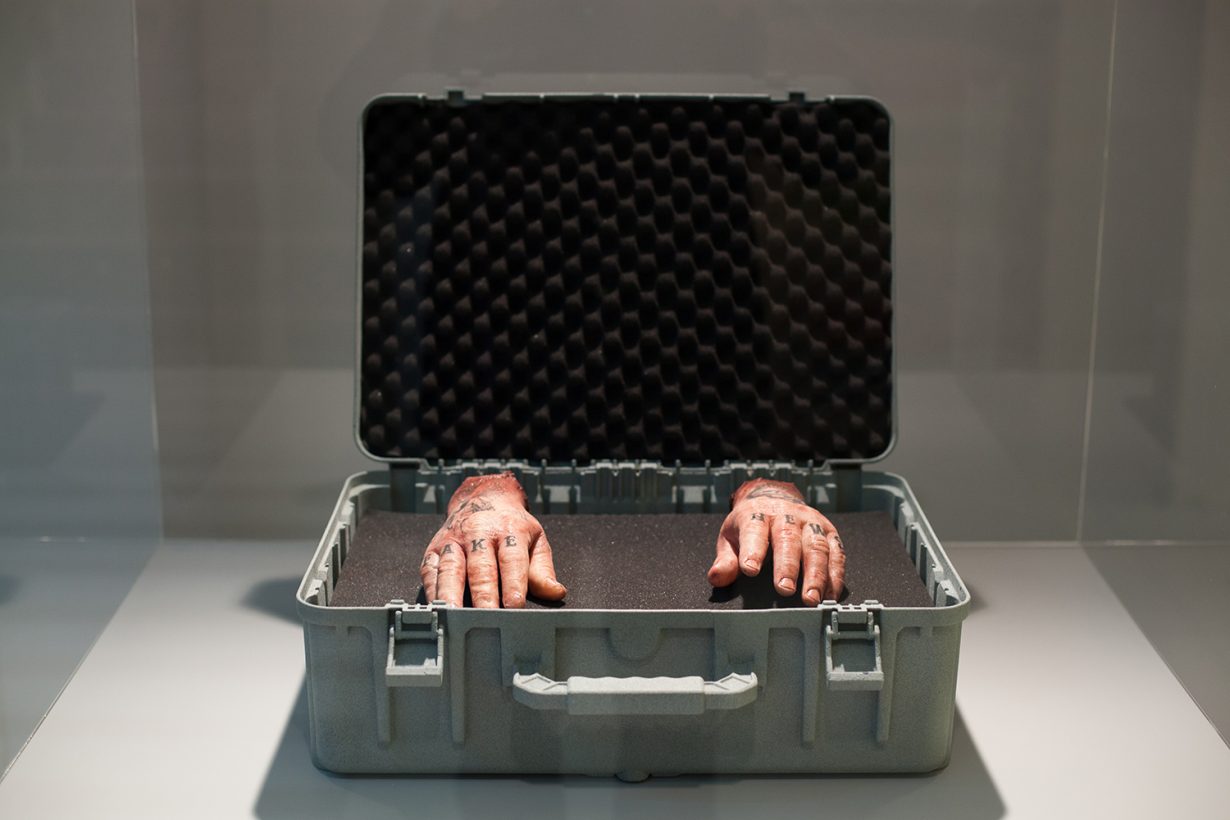

Entering the abandoned department store that serves as the main venue for the Athens Biennale is like walking into George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978). Nor does it take long for the zombies to arrive, with Andrew Roberts’s Cargo (2020) – a sculpture of severed hands onto the knuckles of which FAKE NEWS has been tattooed – and Cajsa von Zeipel’s grotesques – similarly hyperrealistic, lifesize sculptures of conjoined and contorted Barbies in luxury brands – the most painfully literal of numerous jeremiads over the ‘zombification’ of contemporary culture. It doesn’t help that this delayed biennale opens as visitors are suffering from acute disaster fatigue, but the sneering catastrophism would nonetheless feel dated. Walking through the lower floors of a shopping mall filled with lurid objects and screens, I found it hard to avoid the point of a film made 40 years ago: the zombie here was me.

These gloomy reflections were, however, quickly dispelled by Jacolby Satterwhite’s Birds in Paradise (2017–19), a video installation weaving footage of the artist being shrouded and baptised into a digitally animated world that is Boschian in its scale and imaginative scope. In building a new reality, Satterwhite’s dream-logic weaves together Yoruba rituals, rodeos, classical architectures, extraordinary flying machines and the artist’s own dancing body. The sheer vitality of the work is a reminder that disaffection in art is inherently conservative, more typically a sign that a bourgeois creative class is mourning its own obsolescence than a harbinger of the end of the world.

Rodney McMillian dresses up as the archetypal doomsayer for the short video-monologue Preacher Man (2015), displayed in the haunted interiors of the disused Santaroza Courthouse. Yet the sermon he delivers is from the scripture of Sun Ra, repurposed from a 1967 interview with the poet John Sinclair in which the musician and interstellar voyager argues for ‘go-it-iveness’ and creativity as expressions of resistance: “If [you] are obedient and are righteous, then the most appropriate thing to do is to die”. The next world belongs to those who, like Sun Ra and Satterwhite, have the energy and imagination to construct it.

If McMillian’s sermon is to be believed, then Suzanne Treister is among the elect. Ringed around two rooms joined by a ‘portal’ cut into the wall, dozens of watercolours run the artist’s research into artificial intelligence and theoretical physics through the story of an interdimensional time-traveller called ‘the escapist’. Equal parts Hilma af Klint and Douglas Adams, these journeys into the wild fringes of the cosmos and consciousness are made wise by their recognition that what surpasses human understanding is comic. Treister’s esoteric systems find a complement in the design that Navine G. Khan-Dossos and her assistants are painting onto the courthouse’s temporary facade. Inspired by traditional murals on the island of Chios, Khan-Dossos’s work incorporates ideograms that comment on our particular place in the space–time continuum: burning oil drums and the scales of Justice.

Annely Juda Fine Art, London, and PPOW Gallery, New York

A number of compelling works play on this line between information revealed and meaning withheld, what can be decoded and what must remain unknowable. Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s protectively layered and collaged photographs of Black bodies (Exposure, 2020) avert the viewer’s gaze away from what is not theirs to possess, and that theme is extended by the covered face of Kayode Ojo’s Silver (Belgium) (2020), the veiled figures in Yorgos Prinos’s photographic portraits, Kameelah Janan Rasheed’s exceptional short video Keeping Count (2021) and Ndayé Kouagou’s wonderfully slippery meditation on what it means to be ‘seen’ or to side with another (A key is a key and this one is the one, 2021). Even Erica Scourti’s superficially confessional video installation Exit Scripts (2018), composed of voice notes left by the artist on her phone as a free form of self-therapy at times of emotional duress, is made powerful by its fragmentary form and nondisclosure of context. At the Onassis Foundation, Steve McQueen’s End Credits (2012–) draws an austere video-portrait of Paul Robeson from narrated footage of his redacted FBI files that is at once exhaustive and pointedly incomplete. The information gathered by state surveillance, no matter how voluminous, can never capture the personality of its subject. Personhood is fugitive, elusive.

In our panopticon culture, these assertions of the right to be opaque read like withdrawals of the depicted subject from circulation in systems of surveillance and data that are reliant on self-disclosure. They might also be understood as renegotiating the idea of individual and collective empowerment, away from the libertarian version of ‘freedom’ in which the self-promoting individual asserts himself on the world (“If I was ruling,” says MacMillian channelling Sun Ra, “I wouldn’t let people talk about freedom […] the only country that’s causing all the wars [the US] is the one talking about freedom”). In the context of catastrophe, the title Eclipse chosen by curators Omsk Social Club and Larry Ossei-Mensah seems oddly defeatist: these astrological phenomena might look like the end of the world, but they change nothing. The best of this biennale suggests another interpretation: that the most important things are sometimes hidden from view.

7th Athens Biennale: Eclipse

Various venues, Athens

24 September – 28 November