A lot of patina and a strong presence of machines and physical labour carried out by men were the strongest impressions after having worked my way through the Arsenale during my first day in Venice. What I saw felt earnest and fair, and the solid exhibition manages to normalise what was considered extraordinary in Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta in Kassel in 2002: the participation of artists from literally all over the world. However, the mazelike architecture obscured not only my view but also the potential connections between the many multi-original art pieces. I even managed to miss Georg Baselitz’s grand installation. After learning that a number of likeminded friends and peers had done the same, we agreed that it is probably a feminist blindspot, blocking out macho German painters. Nevertheless, three full days of hard work from morning to evening, looking at and in other ways engaging with art in Venice, were not enough to even make it to the pavilions in town. It is simply too much.

One week later I had a diametrically opposed experience, at the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong. Embedded in this nonprofit’s dense library on the 11th floor of a highrise is a jewel of an exhibition, Excessive Enthusiasm, devoted to the late printmaker and sculptor Ha Bik Chuen’s peculiar scrapbooks and practice of documenting Hong Kong’s art scene. Among the material is his faithful documentation of exhibitions in Hong Kong from the 1960s until the 2000s. A selection of negatives, contact sheets and photo albums covering about 1,500 exhibitions is on display on bulletin boards and in small wooden vitrines next to the bookshelves. One series of photos shows artists – the majority male, among them Ha himself – beside their work; another set depicts people mingling among artworks at openings and hanging out in what seem to be studios. A table vitrine is devoted to his ephemera from around the 1967 leftist protests in Hong Kong and the Cultural Revolution in China: ripe for rereading in light of the recent Umbrella Movement. Thanks to Ha’s low-key but insistent practice of documentation, the exhibition team has even been able to reconstruct an entire exhibition – now translated in model form, complete with artworks and a miniature version of the artist sitting where he posed for many portraits.

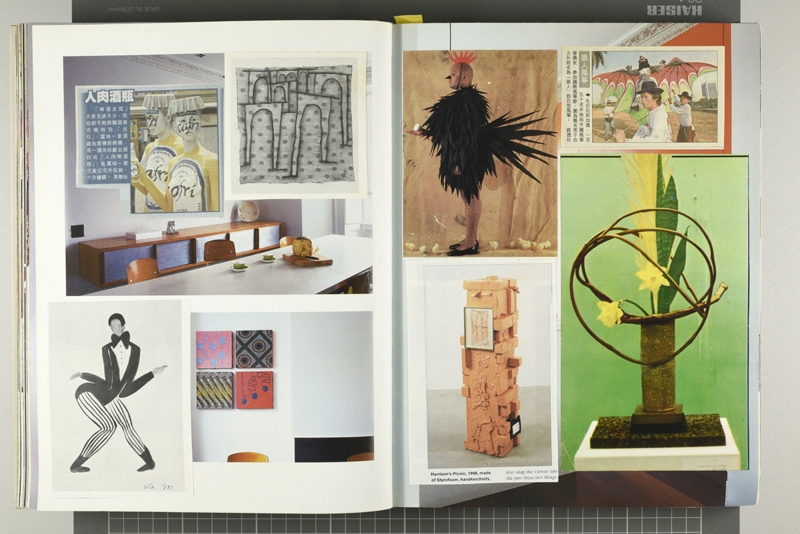

But the most intriguing part of this mini-exhibition is the scrapbooks. Here Ha collected cutouts from colourful magazines, exhibition catalogues and reference books. One page has an image of a man dressed up as a chicken; a Chinese newspaper clipping on the International Kite Festival in Jakarta, where over 150 local and international kiteflying teams participated; and an image of a sculpture by Rachel Harrison. He also photographed art books and recombined images across time and space, creating a personal, virtual world of images, a miniature Asian version of Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (1924–9), or of André Malraux’s ‘Le Musée Imaginaire’ (1947). As in the two older cases, wild connections are made, exploring the beauty of anachronisms.

In order to make as much as possible of the material available, in addition to the digital version on iPads, the team regularly changes pages in the vitrines. This way of activating Ha’s archive is very attractive: a relatively modest volume of material is carefully and intensively explored, playing out the curare part of curating. It is an example of how to maximise the minimal. How to make the most of what is at hand is a principle for aaa beyond the Ha show: it has an ambitious programme of public events, research grants, publishing and residencies, aiming at increasing research, writing and understanding of the recent history of contemporary art in Asia. It was through this that I was invited to go to Hong Kong in the first place.

All the World’s Futures in Venice, on the contrary, is maximised in size, and because of that it reduces, if not minimises, what each work can offer. Geopolitics still play out in terms of who can bring in their own funding, which affects the nature and scale of the work. Even excellent contributions, like those of Elena Damiani, Naeem Mohaiemen, Ala Younis and Massinissa Selmani, feel as though they were treated like poor cousins. Too little of the works’ potential is teased out, it seems. Upon leaving Venice I was exhausted. No wonder, if the exhibition can be said to sum up more than 20 years of Enwezor’s work. Despite the title, the exhibition is retrospective, almost an endpoint, rather than forward-looking. And I’m left wondering: what role does the weight of male melancholia play in this?

This article was first published in the Summer 2015 issue.