The blood of the earth. Ochre slathered our bodies for rituals as we invented them, a primeval makeup on simian faces flickering into consciousness, the only paint we can be sure those first sentient ancestors sprayed and spread and loved. Our Adam and Eve likely didn’t figleaf for the father-god, but ochred their junk for the greater glory of the Supreme Mother.

From the caves of Altamira to the flesh of Beothuk and Maori warriors, humans everywhere found a beauty in this pigment easily smeared from wet clay

Ancient hominids painted their skin and dusted the bones of their dead in this bleeding brown hue that ranges from rusted to jaundiced; whether for worship or a simple aesthetic affection for its tinge, we can never know for sure. From the caves of Altamira to the flesh of Beothuk and Maori warriors, humans everywhere found a beauty in this pigment easily smeared from wet clay, that still crusts the hair and glazes the skin of Himba women in Namibia, and still finds force in wet-paint caking canvases in painters’ studios from Brooklyn to Beijing, though there it stains backgrounds more than features as frontage. The silhouetted hand stencilled in ochre 25,000 years ago in Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc dreams of ancient fathers and mothers, my fingers imagined in theirs on the rough stone, thousands of summers separating our touch.

One of the most abundant minerals on earth, iron exposed lends itself to a host of colours, but ochre is certainly its most ancient pigment. Although standardised in laboratories and factories to a definite shade of brown, natural ochre’s hue varies wildly. Hematite and limonite spread throughout clay richly deepens its skin from ruddy red to mellow gold – changing from place to place, it’s a fugitive hue. The iron makes the colour last; organic pigments crushed from plants succumbed to the millennia, disappearing beyond what science and story can discover. Etymologically, ochre comes from an Ancient Greek word for yellow, but it has since settled into a shade between shanty rust and dying sun, a brown we dubbed Indian Clay as sandbox children who dug too deep.

European painters used ochre unsparingly, finding a fair hue for the ruddy skin of girls with pearl earrings and martyred saints, but this sanguinary shade has fallen out of use, reserved for the rutted dirt roads, dusty places and earthen people. Across literature, the word still colours but rarely. Each time the writer fingers an array of colours, in a likely list from a well-thumbed thesaurus, they find in the curl of its colour and the sound of its stutter a perfect poetry:

Oh Cur, Oak Her, Oke Ur.

Half-choked, it still rolls.

I see ochres in old port towns, rust-belted and terminal. Leaked from the wounds of dying iron, not rust but its bleed on weathered wood, dripping down into the cut seams and folds of buildings, the paint flaked and clinging to only the saddest fade of its wet youth. If Serra’s steel monuments could bleed, they’d bleed ochre.

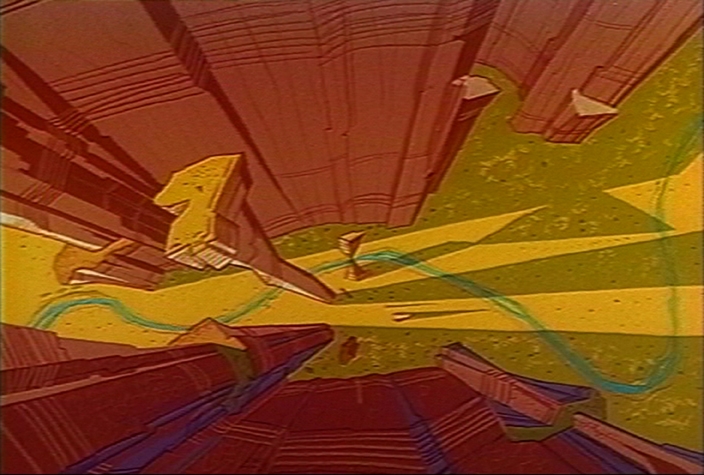

Its smear is spotted in stones littering Monument Valley and the American Southwest, the bands of ochre ringing pale rock in dusted desert cathedrals more sublime than humans can ever craft. Ochre colours the arches and buttes where Wile E. Coyote’s technical genius always fails to defeat the Road Runner’s native intelligence and natural grace, never, ever sinking those cartoon canines into his evasive prey.

A generation of minimalists and Land artists favoured the American desert. They found in Coyote country a freedom to act and make far from civilisation and its corruptions

A generation of minimalists and Land artists favoured the American desert: Michael Heizer to cut his city of stone, James Turrell to carve out of a caldera a naked-eye observatory and Noah Purifoy to assemble a junk garden. They found in Coyote country a freedom to act and make far from civilisation and its corruptions, and so do Alma Allen and Andrea Zittel and all the artists in High Desert Test Sites along with countless other freaks and weirdos, visionaries and geniuses still sifting their ideas through the desert dust.

In ochre we find our most ancient connections to the land and its colour, where technology reveals itself as that mechanism that not only fails to deliver desire but will likely lead us to our eventual self-destruction.

The Road Runner, never caught, always free, again and again leaves his enemy eating dust, tinged just for me with the softest whisper of ancient ochre.

This article was first published in the Summer 2015 issue of ArtReview Asia.