The prehistoric desert paintings inspiring a new generation of artists

Named after desert rivers that have dried long ago, the remote plateau of Tassili n’Ajjer is found in south-eastern Algeria bordering Libya and Niger. More than 15,000 prehistoric drawings and engravings have been recorded in this area, which is larger than Switzerland or Greece and was classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982. A visual testimony to the dawn of humanity and art, the site also inspires a new generation of Algerian contemporary artists to resignify ancestral pasts as places of negotiated alterity and belonging.

Getting to Tassili n’Ajjer requires days of trekking which often involve riding camels or donkeys. Then you arrive at a place that feels other-worldly, labyrinthine, so unlike the imagination of vistas of sand dunes. Many visitors have described it as Martian. There are vestiges of Tuareg tombs and hundreds of tall sandstone pillars eroded by water and wind that constitute a rock forest. Save for some cypresses, the site looks barren at first; it’s anything but. Humans have drawn on the sandstone of Tassili n’Ajjer for 10,000 years, up until around 2,000 years ago. The result is a site populated with images depicting various characters and scenes, including humans engaging in hunting and pastoral activities, as well as animals such as antelopes, sheep, goat and cows. More stirring are the large-scale humanoid forms representing floating, round-headed silhouettes. A five-metre-high divinity towers over the viewer, left to absorb the mystical and cosmic evocations of the Great God of Sefar (named after its location). French archaeologist Henri Lhote ‘discovered’ the site in 1935 and contributed to its popularisation from the 1950s onwards, in the publication of a book presenting the paintings and an acclaimed exhibition in Paris following a series of expeditions during the 1950s and 60s. Lhote believed in the paleocontact theory, arguing that the paintings of Tassili n’Ajjer represented alien life.

Algerian artist Lydia Ourahmane visited Tassili n’Ajjer for the first time in 2019 after fellow artist Sophia Al Maria slipped a note into her hands during a residency. The note showed a drawing of the Great God of Sefar and the words ‘take me to Tassili’. Ourahmane undertook the journey. In the resulting video, Tassili (2022), she explores the site over the course of a frenetic, lucid dream, engaging with silences, vivid images and altered states – a choreography in which Ourahmane probes the depth of vertigo and disorientation.

Early in 2022, Algerian-born artist Dalila Dalléas Bouzar arrived in Djanet, Tassili’s gateway. Her guide informed her that another artist – Ourahmane – had just left. Dalléas Bouzar, a long-time admirer of prehistorical art, had just been awarded the 2021 SAM prize for a project that was inspired by reproductions of the drawings in Tassili n’Ajjer. She wanted to see the images for herself, not knowing what may emerge from it. She gasped at kilometres of frescoes. “I’d never seen anything like it,” she told me in conversation.

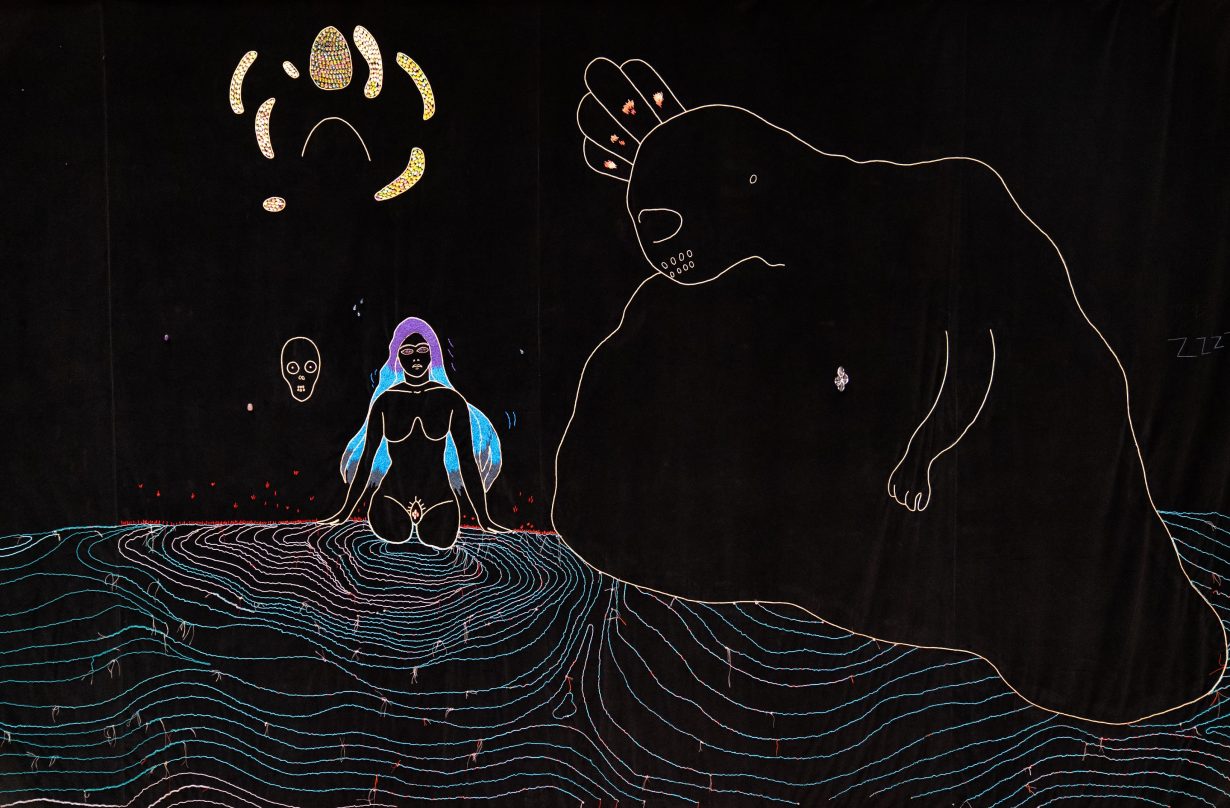

Dalléas Bouzar turned her in-situ esquisses into a monumental tapestry installation, Vaisseau Infini (Infinite Vessel), which is on view at Palais de Tokyo in Paris through 7 January 2024. She partnered with Algerian embroiderers to reconstitute several of the Tassili n’Ajjer Round Heads and insert other figures using a style traditionally associated with wedding attire. In doing so, Dalléas Bouzar weaves womanhood and cosmology into the work, perhaps emulating the force of the Running Horned Woman in Tassili, painted around 6000–4000 BCE, or the words of her guide, who told her that the Tuareg herdswomen knew best where the paintings were. Tassili n’Ajjer lends itself to decentring dominant perspectives. Dalléas Bouzar channels this intention in large panels that offer a new cosmovision united by life, where humans, spirits, names and plants coexist and are embraced as a form of resistance to entropy and death. Against Algerian narratives dominated by colonial and postcolonial trauma, Dalléas Bouzar considers the site as alternate space-time. Dalléas Bouzar claims the right to artistically approach this fraught history and challenge imposed paradigms. “We existed before”, she told me, as we discuss how systems of domination and power have shaped identity formation, the relationship between people and land, and access to knowledge.

Encounters with Tassili’s universe allow artists to examine the uncanny as a boundless energy towards self-affirmation, and Dalléas Bouzar and Ourahmane are far from the only Algerian artists to express an attachment to prehistorical art. Just as the Altamira and Chauvet caves profoundly moved Pablo Picasso, Tassili n’Ajjer anchored the creative quest of emerging modernists searching for a renewed Algerian aesthetic and identity, which would free itself from colonial impositions. In 1967, Algerian artists Denis Martinez, Choukri Mesli, and several others including Baya, founded the Aouchem (‘tattoo’) group, the name praising a symbol of permanence and Indigenous culture. ‘Aouchem was born thousands of years ago on the walls of a cave in the Tassili mountains’, their manifesto began, as the group reclaimed signs and magical visual codes as a decolonial proposition to the dominance of Western art. For example, in Afrique avant 1 (1963), pioneer modernist and Aouchem member Mohammed Khadda shows a totemic anthropomorphic figure directly inspired by the Tassili n’Ajjer paintings. His painting’s style matches Mesli’s Sunset of the same year, which similarly uses pigment imitating earthy ochres applied to a more abstract expression.

That such a lineage of artistic exploration should resonate with places deemed inhospitable comes as no surprise. The Algerian desert has long been an area of contestation and empire, from the Arab conquest to the emergence of jihadism by way of archaeological extractions and wastelands created by French nuclear weapon tests during the 1960s. Part of Tassili n’Ajjer is a military zone. The paintings and engravings there offer a counter-narrative to this violence, transcending the notions of brutalising borders, monolithic spirituality and excluding geographies. Rather, they become dream-spaces of North African futures.

The Aouchem artists have turned to the distant past at a critical inflexion point to express an evolving interpretation of national identity, between tradition and modernity, as they transitioned from indigènes status to emancipated citizens. Tassili holds potency because it is anchored in liminality and translatability at the convergence of Arabness, Africanness and Amazigh culture, where expansive genealogies can be narrated and carried into the present.

In the context of rising political and economic disenchantment propelling North Africa as a departure point for disillusioned young people to Europe and elsewhere, engaging with prehistory provides a lens by which to revoke restrictive designations and overcome despair through a different sense of belonging to the place. This forward-looking archaeological approach has elicited interest from other contemporary artists in the region, such as Tunis-based artist Bochra Taboubi, who dreams of visiting Tassili one day. For her work Cluster of Matter (2022), she created a hybrid museum of fossils (some real, some imaginary) based on the paleontological profile of Metlaoui in southern Tunisia, an arid zone ravaged by phosphate extraction, its associated socio-environmental degradation, as well as unemployment and widespread hopelessness. “Prehistorical art is an aesthetic that speaks to me, and it’s a semiotic approach as well”, she says. In her practice that blends artistic, speculative and scientific aspects, Taboubi questions the notion of missing archives. Through engaging with historical discontinuities and abstracting fossils, Taboubi marries fiction and reality to create interstitial experiences and vivid testimonies of springing life.

Prehistory’s material strangeness is used as a device to question the singularity of the present. Communing with alternative and speculative stories offers grounds of empowerment, which makes dreaming of common futures conceivable. Since a dialogue with the distant past involves mediation and a degree of alteration, the sites become a reflection of contemporary concerns related to identity. They can thus act as springboards to reclaim agency and rootedness more broadly, as possible antidotes to exile and resignation.

Farah Abdessamad is a French Tunisian writer based in New York City