A brief history of a humble little pastry

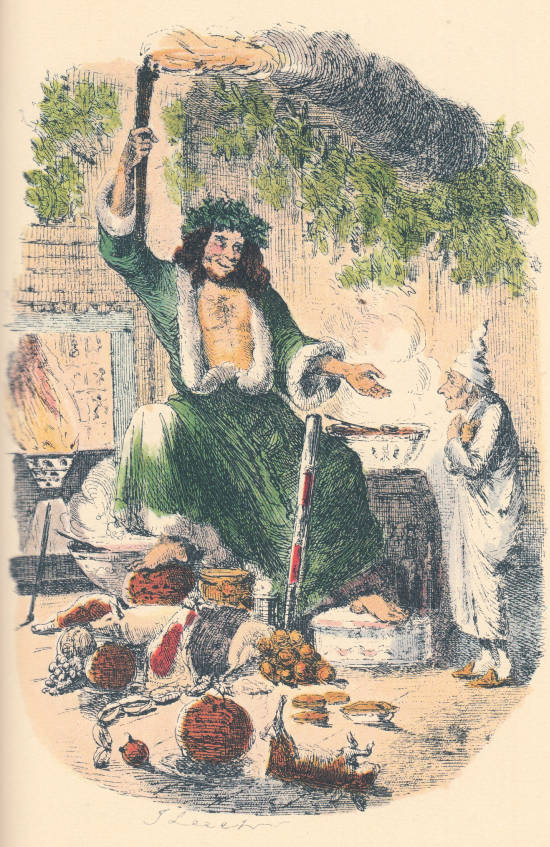

’Tis the season of mince pie-making, mulled-wine drinking and merriment, and I have fallen into a rabbit hole researching the humble little pie that is (probably) one of the oldest foodstuffs currently scoffed during Christmas – albeit with a slightly tweaked recipe. Today, the popularity of mince pies causes media outlets to scramble to publish their lists of ‘Best Supermarket Mince Pies’ each year – but to be honest it doesn’t really matter which store-bought ones you stuff into your mouth; they’re all disgusting. Take my advice and avoid the forewarned mince pie shortage by making your own versions. So ubiquitous are mince pies in the Anglophone world that variations on the treat appear in English literature from Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1603) (‘Thrift, thrift, Horatio! The funeral baked meats/Did coldly furnish forth the marriage tables.’) to the Ghost of Christmas Present’s throne of Christmas fare in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843) to Charlotte Brontë’s eponymous Jane Eyre (1847), who busies herself with the ‘beating of eggs, sorting of currants, grating of spices, compounding of Christmas cakes, chopping up of materials for mince-pies, and solemnising of other culinary rites.’

12 cm x 8 cm. Fifth illustration in A Christmas Carol (London: Chapman and Hall, 1843), facing p.78. Photo: Philip V. Allingham / Victorian Web

The earliest English cookbook, The Forme of Cury (c.1390), documents numerous recipes for tarts and pies that include meat, preserved fruits and spices, a mixture generally known as mawmenny:

‘Take pork ysode; hewe it & bray it. Do þerto ayren, raisouns corauns, sugur and powdour of gynger, powdour douce, and smale briddes þeramong, & white grece. Take prunes, safroun, & salt; and make a crust in a trap, & do þe fars þerin; and bake it wel & serue it forth.’

This recipe, written in Middle English, and many similar renditions in The Forme of Cury, have culinary roots that trail much further back in history and across geographies – to the tenth-century Arabic cookbook Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Dishes, c. 950s) written by the Baghdadi author Ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq. In this compendium of foods and recipes collected from across the region known as the Fertile Crescent, where the practice of drying fruits was a more common method of preserving than in the West, al-Warrāq records stews from Persia, such as sikbaj or zirbaj, which often contained mutton, beef or poultry cooked in a sour-sweet juice made of vinegar, preserved fruits and spices. As for the spices, those such as cinnamon, pepper, cloves and nutmeg were a secret closely guarded by Arab traders: one fanciful tale told to their rivals in Medieval Rome and Greece includes that of the ferocious Cinnamologus, a giant bird that built its nest with cinnamon sticks collected from an unknown land, and from which they had to steal the coveted spice.

In the twelfth century, European crusaders brought these ingredients back to the West, which were introduced to the kitchens of the wealthy: the stews, baked into a ‘coffin’ (a thick, hard pie crust that was less about eating and more about ease of transport and preservation), became a dish reserved for festivities and Christmas celebrations because of the rare and expensive spices they contained from the ‘Holy Land’. A few centuries later, European merchants and traders began to bypass their Arab suppliers, going straight to the source in Southeast Asia (and resulting in the colonisation of those islands in an attempt to gain monopolies on the spice trade). With spices more accessible, the mince pie – also known at various points as ‘shrid pie’, ‘mutton pie’ and ‘Christmas pie’ – became common fare around Christmas, when it was baked into oblong shapes to represent a baby’s crib, topped with a little pastry Jesus. (These quickly went out of fashion in the seventeenth century, when Puritan England frowned upon idolatries and luxuries, as evidenced in Cromwell’s propagandist Marchamont Nedham’s 37-page poem: ‘All Plums the Prophet’s Sons defy,/ And Spice-broths are too hot;/Treason’s in a December-Pye,/ And Death within the Pot.’) Mince pies contained meat until the late Victorian period when the ingredient was largely dropped in favour of the sweet flavours of the fruits encased in a puff or shortcrust pastry.

If you’re too lazy to prepare the filling (like me), at least put some effort into a buttery, crumbly, crisp pastry. Then, as you set a plate of freshly baked pies on the table, you can (like me) bore your guests with the complicated history of this festive food. Now where’s my throne of mince pies?

From the December 2021 issue of ArtReview