A guide to which artworld forces have defined ArtReview’s Power 100 list

Explore the 2024 Power 100 list in full

Back in 2002 when ArtReview’s Power 100 first appeared, the list hadn’t yet begun to group its power players into categories, though ArtReview knew enough to draw attention to the ‘artists, patrons, dealers, directors and collectors’ that it had decided constituted the ‘art/power axis’. A year later, it had identified ‘curators’ and ‘theorists’ as important power types. So to stop things from getting too serious the 2003 list also threw in a doorman and a dentist. Don’t worry, reader, they were only there for laughs (laughing was a thing in the noughties), ‘characters’ not categories, exceptions not types.

By 2004, ArtReview had got its act together and started making power lists out of the Power list, handily sorting out four top tens – of artists, collectors, gallerists and museum directors – so that ArtReview’s readers didn’t have to crunch the numbers for themselves, or perhaps do the hard work of thinking it all through using their own thoughts. And by 2006, the Power 100 was starting to discuss its categories, which now included ‘critics’ and ‘architects’, observing that critics were few on the list since ‘the function of critics has passed over to curators’, while architects (this being the wild age of frantic museum-building) could shape ‘the way everyone views art’. By 2007, ArtReview had become obsessed with breaking things down, assigning categories to the list’s entries upfront, while starting to spin off statistics, pie charts and infographics to sate its increasingly megalomaniacal desire for to fit everything in the world of art power into visible trends, tendencies and, yes, categories.

Compartmentalising gives the knowledge-hungry a way to break down reality into what’s important and what’s not. Anyone following the aftermath of US presidential election will hear pundits breaking down the various demographic combinations which propelled Donald Trump to victory – was it the non-college educated voters, or the young white men, or working-class, socially conservative, Rust Belt swing voters that made the difference, or… who, exactly? Working out why one or the other category made the choices they did is another matter, as old assumptions about who normally votes for one or the other party have been upended.

But the Power 100 isn’t about democracy (have you ever heard a curator offer the public a vote on their next biennial theme, or a gallerist ask the little people whether they actually like any of the work the gallerist shows? No? That’s right, because that’s insane, even if all art is about decolonising privilege, and so on), and while in this year’s Power 100 the big categories remain, it’s worth paying attention to what might be going on inside these monolithic artworld groupings.

One big change to take place – after ArtReview had been relentlessly harried and pestered about it by its anonymous committee of advisors – is the merging of ‘collector’ and ‘philanthropist’ into the bigger and broader category of ‘funder’, a change which tries to makes sense of how the biggest players, once happy merely to sit in their armchairs and collect art, have become something more complicated – institution builders, programme enablers, artist patrons, thought-leader sponsors, conference organisers and more. Rather than following agendas, such figures are increasingly using their financial power to set them.

That full-spectrum approach to supporting one form of art over another, in the name of broader social and cultural agendas, points to a more general shift within all these power groupings; that the most important figures these categories are often notable because they go beyond the narrow confines of what traditionally was thought of as their particular role in the art system. So the artists on the list are where they are not simply because of the strength and influence of their work, but because their activity extends into broader activities – activism, education, organising. Curators reach beyond the simple organising of shows in their own institutions to organise biennials simultaneously, or lead activist organisations while advising other institutions keen to tap their expertise. Gallerists, meanwhile, are extending into becoming ‘lifestyle purveyors’, catering to the whole collector ‘experience’, while encroaching increasingly on the role of museums. Museum directors, for their part, are finding that the museums they have shaped now do a great deal more than look after historical collections – becoming bigger forums for public culture, with all the competing claims and demands that come with it – while spinning satellites of their parent institutions ever further afield. Can the old categories hold, or is it time that new hybrids of power were given names?

Artists

Curators

Funders

Gallerists and Art Fair Directors

Museum Directors

Thinkers

Artists

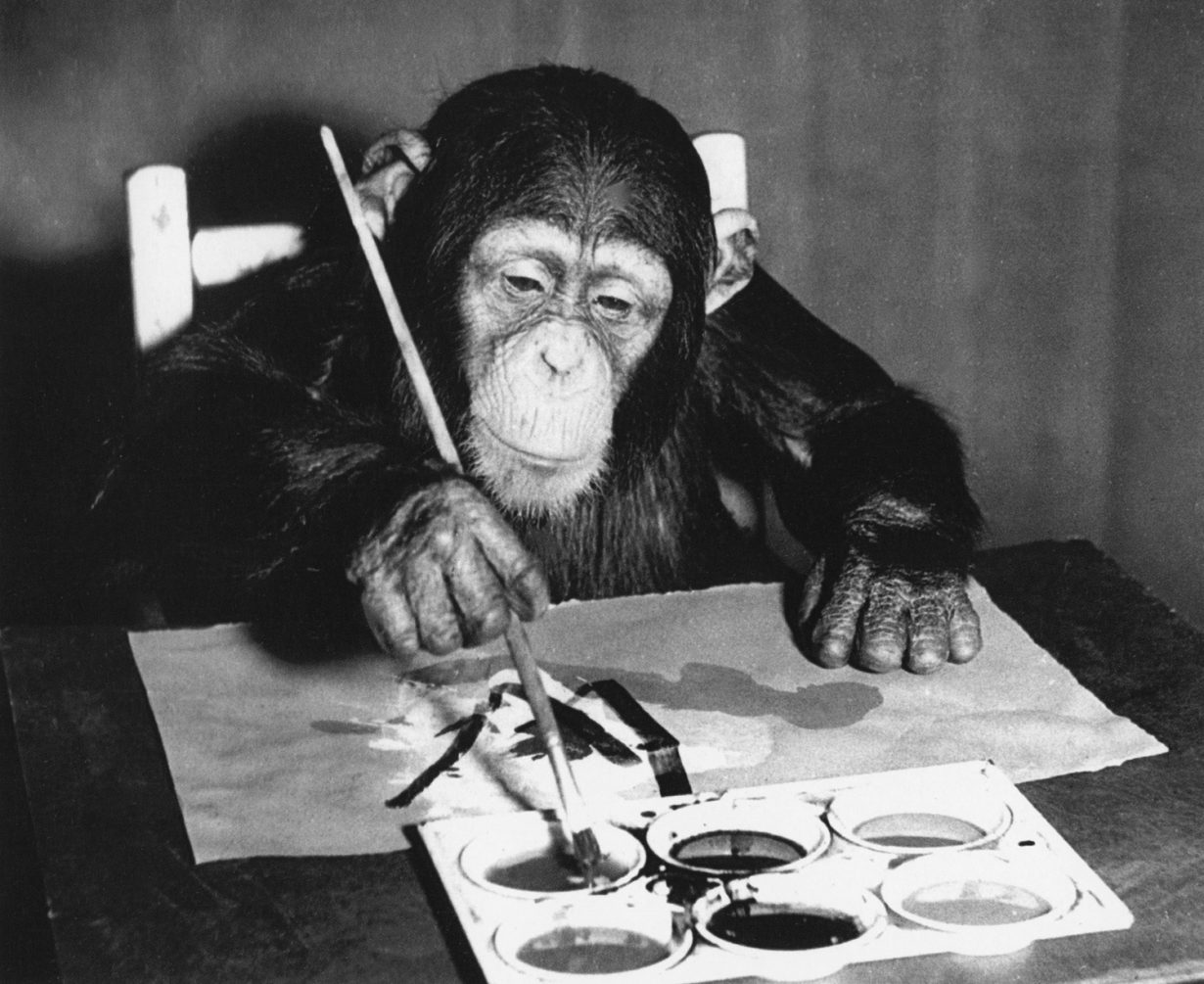

The commonsense definition of an artist is someone (still necessarily a person – former ICA London director Desmond Morris’s championing of the work of Congo and Betsy, chimpanzees residing at the London and Baltimore zoos respectively, never really took off as anything other than a novelty, though Morris did manage to curate an exhibition of their work at the institution in 1957) who creates objects or experiences that defy classification. ‘What artists do cannot be called work,’ wrote Gustave Flaubert in his posthumously published Dictionary of Accepted Ideas (1911), tongue firmly in cheek. Or, to be even more old-fashioned, artists create things that have no use-value. For the purposes of this list, they also make the stuff (artworks) around which the rest of the artworld ‘system’ orbits. Although from time to time it might be less than clear as to what’s orbiting around what. Which is in part why this list was originally ‘invented’ and why it goes through some degree of annual change (although it’s not without precedent that the people at the top stay at the top). Indeed, this year artists make up around a third of the people on the list. The remaining two thirds of the list relates to people who do something with the stuff that the artists create. People who may or may not like art, but know how to use it (a curator, for example, tops this list). Which tells you a lot about how the system of art operates. But may also be nothing particularly new either.

What is at stake (on a regular basis, if past lists are anything to go by) is art’s fundamental nature. From this list, you might divine, for example, that we expect art to have an intrinsic truth-value. This would be why so many artists, such as Nan Goldin and Forensic Architecture in particular, set themselves up as crusaders for justice, private investigators or practitioners of what is generally known as artistic ‘research’. (The last of which cruel academic types might describe as research without the rigour of the academic.) You might conclude from all this that it’s not enough, today, for art to please the eye or even the soul; rather it needs to be for or against some part of the mechanism of civic life. It needs to have impact in the ‘real’ world as much as the artworld.

For these reasons also you’ll find that a number of artists on this list – Mark Bradford, Theaster Gates, Yinka Shonibare, Dalton Paula, Sammy Baloji and Ibrahim Mahama, for example – don’t just make things to put in galleries or museums, but also fund organisations dedicated to providing opportunities for others to overcome the social and economic hurdles that generally exist in maintaining art as a preserve of the rich or the otherwise privileged. Operating in a similar vein, you’ll find others, the Lusanga-based Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise collective, for example, who use their work and the value it commands to establish a postplantation ecology in their homeland. Or Julie Mehretu, whose multimillion-dollar donation to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York enabled the institution to provide free entrance to those aged twenty-five and under for the next three years. Then there are the artists who appear on this list not for their artwork at all, but for the organisations or institutions they helm, such as Bose Krishnamachari, cofounder of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (which notably always has an artist as its artistic director) and Christopher K. Ho, executive director of the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong. And then there are those who seem to do it all, like Rirkrit Tiravanija, who produces innovative, often participatory artworks, cofounded a commercial gallery (Ver, in Bangkok) and curates exhibitions (the Thailand Biennale in 2023–24, for which he was co-artistic director, and Art Spectrum 2024, titled Dream Screen, at the Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul, for which the Thai artist was artistic director and cocurator).

The real question though is why we expect art to do all this. And whether the expectation that it should do these things is proof of the many shapes that art might take, or the result of the failure of other systems that should form the fundamental structures of society in general. Whether or not it’s proof, if you like, of just how fucked up is the world in which we currently reside.

Curators

Despite the proliferation of specialist university courses dedicated to the subject, no one really knows what ‘curating’ means anymore. That’s not because of a lexicological crisis as such, but due rather to the activity’s increasingly wide parameters, which has led to its ubiquity. At this point, everything has the capacity to be curated, from capsule collections in fashion stores and bookshelves in hotel lobbies, to the drinks being served at your local bar: in short, any undertaking that involves choosing some things over others. ArtReview’s more revolutionary friends might see such an act as a form of censorship. Because prioritisation of any kind could be construed as just that. And only the refusal to choose could be equated with any notion of fairness. And yet in practice the option to abstain from any selection process never seems to be anyone’s first choice, and before you know it, a curator turns up, raring to go.

It is fair to say that the curator occupies a complex position in the current climate, what with the art being produced today purporting to be a zone of justice (see the entry on ‘Artists’ for more on that). One way of resolving, or denying, that complexity manifested at this year’s Venice Biennale, where curator Adriano Pedrosa made a point of emphasising the fact that he was choosing artists who hadn’t previously been picked for the biennial as a result of (it was implied) racism, sexism, colonialism, ableism, homophobia and various other prejudices. His Foreigners Everywhere exhibition might have come across like a salon des refusés for our contemporary times. A diatribe against conformity. Even if the real act of rebellion here might have been to select everyone or no one. But this is not the place to construct an archaeology of curatorial failings, nor contradictions – after all, this year’s list sees a curator in first place.

Traditionally, views relating to what curating might actually entail – within the context of the artworld, that is – have typically centred on those who take responsibility for works of art (the word is derived from the Latin curare, to take care), which allows cruel people to cast curators in the same vein as caregivers in an old people’s home. Because, as others have said before, museums are where artworks go to die, having been stripped of any connection to the societies and realities that generated them. Contemporary perspectives on curating, though, relate to how artworks can be massaged into arguments. Operating, if you like, at some sort of nexus at which theory becomes practice: these are the issues that art is supposed to care about (again, see the entry on ‘Artists’). In general, these are things that society at large doesn’t care about, or as is the case with the natural environment, pretends to care about. Because art (and by extension curating) is always about looking at the overlooked, not at what everyone is already looking at. (As the Venice template cited earlier demonstrates, this thought extends to artists from the past who were overlooked during their own lifetimes and are therefore now deserving of an extensive reappraisal. In the name of justice.) If such requirements weren’t being met, why would anyone go to an exhibition in the first place?

However, there are times, like the one we presently occupy, when addressing things that people may not be addressing, or reinforcing voices that society has largely silenced, does carry weight. That’s because venues outside of the artworld where such activities might be welcomed are notably diminishing. And because the space, whether literal or otherwise, for presenting alternative points of view is becoming few and far between. We are in a time of cancelling on both sides of the political spectrum. Although you could also argue that the artworld itself, where cancelling is rife, has a propensity for advocating a point of view that will conform rather than result in any conflict.

Curating today, then, isn’t merely a matter of ensuring that art exists within both public and private spaces, but is instead about ensuring that something has been done with it. And what an artwork does, we are realising more and more, depends on context. On when, where and how it is displayed. The same artwork shown in Beirut right now, for example, is very unlikely to read in the same way when it is eventually exhibited at a New York gallery, regardless of where the work was originally produced. And being sensitive to these changes, and the resulting effects, is what will determine the real efficacy of the curator working in this moment.

Funders

Back when the Power 100 was in its infancy, the big-spending individuals on this list were known simply as ‘collectors’. After making their mark with their million-dollar collections, these megabuyers of artworks, mostly male or occasionally a married couple, then realised that they needed to build private museums and galleries to show off (at least some of) the things they had bought. Pinault, Arnaud, Cohen, the Broads – these were the names that conjured up the spending power of the ultra-rich. Collectors made the art market go round, or so conventional wisdom would have it, and to a large extent the rising fortunes of galleries and the art fairs that they exhibited at were founded on the global expansion of the collector class. According to this year’s annual art market reported prepared by UBS and Art Basel, those collectors bought $65b worth of art in 2023.

But when it comes to buying art, things aren’t what they used to be. Over the past decade, using one’s major assets to influence the workings of the artworld has evolved into something more elaborate than the narrow, largely transactional relationship between gallerist and collector, which is why ArtReview has this year taken the categories of ‘collector’ and ‘philanthropist’ and merged them to reflect something that feels more accurate: ‘funder’.

In part this new category reflects what the old-school collectors have become, namely founders of institutions that seek to shape the contemporary art discourse while catching the attention of the wider community. Such individuals are increasingly placing their focus on infrastructures within the industry itself, using their money to finance programming, residencies and awards that benefit artists and curators, while their organisations take a more active role in directing the artworld’s critical agendas. Miuccia Prada’s foundation, for example, stages thematic exhibitions year-round in Milan, Venice, Shanghai and Tokyo, while investing in collaborative activities through its ‘Human Brains’ project – a series of neuroscience-focused shows, conferences and publishing initiatives that have resulted from multidisciplinary research undertaken since 2018. Similarly, Maja Hoffmann’s LUMA Foundation presents a host of curated exhibitions at its huge campus in Arles, while this year saw the third edition of its annual conference on ‘Environmental History’ (the cultural centre also supports eco-conscious and tech-tinged programmes further afield, such as at London’s Serpentine, where LUMA adviser Hans Ulrich Obrist is artistic director). In bringing together artists and architects with scientists and psychologists, through initiatives like those noted, funders make a case for themselves as facilitators of a much bigger set of cultural and social objectives, of which art is only a part. Of course, such a direction isn’t exactly surprising given that so much contemporary art directly intertwines with other fields, whether politics, academia, science or social activism. Consequently, private funders have had to shed their roles as mere collectors or museum makers, while being increasingly proactive about what they fund and increasingly thoughtful about their reasons for doing so. It’s why Darren Walker appears on the list, head of the Ford Foundation, one of the biggest philanthropic foundations in the US, which, in 2023 alone, gave over $64m in grants supporting ‘creativity and free expression’.

Funding, then, is increasingly a form of soft power, which extends everywhere. Kiran Nadar’s collection is a reference point for modern and contemporary art from India and the subcontinent, and her eponymous museum, gearing up to open its new building in Delhi in 2026, projects its own view of India’s postwar artistic history. Recently it loaned a number of major works to an exhibition that it also helped fund, at London’s Barbican, that charted Indian art in the late twentieth century, and presented an exhibition about the pioneering painter M.F. Husain at this year’s Venice Biennale, where, notably, India has only twice been officially represented. Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani, through their Dhaka Art Summit, connect the global artworld to Bangladesh’s contemporary scene. And it’s soft power that also defines the presence of the Gulf states on this year’s list: Saudi Arabia’s minister for culture, Badr bin Abdullah Al Saud, is largely responsible for modernising (and internationalising) the country’s cultural profile; Qatar’s Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani heads up what is an ever-growing group of museums in Doha; and the list’s number one entry, Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, drives forward the UAE’s well-connected and influential Sharjah Art Foundation, while also a curator being tapped to lead biennials and triennials abroad.

Of course, collecting is still a key activity for these funders. It’s just that acquiring art has now been integrated as part of a greater vision that considers how wealth can be directed towards other, very particular goals, whether influencing global agendas or reconfiguring a country’s profile on the world stage. Does art end up as a pawn used to play much bigger games? Probably. And, from the Catholic Church to the CIA, it probably always has been.

Gallerists and Art Fair Directors

Aside from playing a vital role when it comes to career management, galleries, even more importantly perhaps, provide the artist with a source of income. In keeping the artist away from the grubby side of finance, galleries help to preserve the illusion that their dependants are in fact aloof from such distractions and dedicated wholly and exclusively to art. Of course, this is how the artist is still often perceived within the public imagination: as some sort of dreamer, detached from, and perhaps unburdened by, the realities of everyday life.

Let’s remind ourselves, then, that galleries are shops – places where (some) people go to buy art. Why someone chooses to spend their money on a painting or sculpture is not important here – it might be because they find it beautiful, thought-provoking or simply ‘interesting’, or that they think it’s funny (in a comedic sense or otherwise), or that by owning it, aspects of their personality that may not actually exist could be revealed: that this artwork could make them appear interesting and sophisticated within their social circle or the one they aspire to join. Or they may simply figure that whatever they’re buying is going to make them even more money in the long or (preferably) short term. But, like ArtReview said, the whys do not matter here. Unless, of course, you’re a gallerist and therefore responsible for giving all potential shoppers a reason to spend their money with you. As such, a successful gallerist will be adept at keeping these diverse factors in play.

Nevertheless, galleries are a curious kind of shop. The aesthetic experience that they’re ultimately trying to sell, often interchangeable now with some sort of ethical experience, is available to all who visit, regardless of whether they’re in the market for a piece of art. Being a powerful gallery isn’t just about selling lots of art, then, but instead about being motivated to give a platform to artists who call into question all of the dynamics that are involved when engaging with art, while staging exhibitions that inform our understandings of art being made today. The galleries on this list tend to combine the former with the latter.

Going back to money: the art market has seen something of an economic downturn over the past 12 months (insiders call this a ‘correction’ in an attempt to normalise such a decline and reduce any negative connotations). Zealous aesthetes might interpret such a plunge as an upturn, believing that the artworld could now operate on its own terms without having to accommodate the needs and desires of those who fund it. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction, as Isaac Newton was fond of telling anyone he caught dodging the falling apples in his orchard. The real point being that everything can mean what we want it to mean. Which is not to say that the world is meaningless, even though some cynics might suggest that’s the case, but rather that it is open to interpretation: it’s a sort of ‘multiverse’, to use the language of today’s children. Ultimately, it’s that (the openness, not the language of children) which forms the founding principle of the contemporary religion of art. And as the current spate of cancellations and boycotts against organisational structures persists, demonstrating the readiness with which artists have taken considered (or specific) positions with regard to world events, it will be the collectors and institutions who hold the artworld to that principle. What goes around comes around, as Newton probably didn’t say.

Sales of art at auction were down by around 26 percent during the first half of this year according to the annual collecting survey compiled by UBS and Art Basel, published in October. Global turmoil was to blame, along with the many elections that took place, in addition to the relatively stable status of other investment assets (treasury bonds and the like). The consequence of all this is that many small-to-medium-sized galleries have been struggling to survive. Traditionally viewed as the kindergartens for new artistic talent, such galleries have become even more sensitive to the often extortionate costs that participating in global trade fairs incurs – an activity that is now regarded as an essential part of the art market ‘game’. Of course, there have also been concerns about the environmental impact of constantly circulating art objects all over the world, not to mention the people to install them and the people to sell them. But sometimes this is just a loincloth to cover up deeper financial concerns. It’s been a tough year for galleries all round. Which is one of the reasons why, this year, there are fewer of them on the list, and why even the biggest, most international and globally present galleries have tended to fall in the rankings. But there’s another component to the turmoil that galleries have recently been experiencing, one underpinned by a growing sense that where you stand nowadays (politically, ethically) is more than ever under scrutiny, and that remaining neutral is increasingly difficult. If experiences based on aesthetics are becoming increasingly ethical, or political, that’s not a development that galleries today can so easily influence.

Museum Directors

‘Citizens don’t trust politicians or the media, but they do trust museums. We have an obligation to them,’ stated Suhanya Raffel, director of M+, Hong Kong, and president for the International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art (CIMAM), in an interview earlier this year. Although in light of current debates around issues of restitution, repatriation, representation and the aftereffects of various forms of colonisation, it would be foolish to take the public’s trust in any museum for granted. Yet, whether you believe Raffel or not, such issues of shared values, civics and belief in the public institution are certainly at stake in today’s art museums.

Museums are under more stress and scrutiny than ever before: what do they actually do? What should they do? Who are they for? Should they even exist? A slew of books released just this past year attempted to answer that question, from Tate director Maria Balshaw’s vision of the museum as a site for hosting society and its disagreements, a sort of contemporary Greek agora; to curator and writer Fatoş Üstek’s call to network the museum and restructure it less hierarchically; to scholar Eunsong Kim’s and thinker and activist Françoise Vergès’s indictments of the biased foundations of museums themselves.

There does, however, seem to be a tacit agreement that the museum is a shared and very visible space, simply based on the number of protests over the past year that used art institutions as the stage from which to make a public statement. Buildings have been occupied and exhibitions have been closed down with climate protests and groups protesting artworks or events they view as problematic. The year began with pumpkin soup dashed all over Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503–06) in the Louvre in the name of sustainable food systems, while in June Claude Monet’s poppy field at the Musée d’Orsay was pasted over with a desert wasteland scene. The same day this September that protesters were handed a jail sentence for throwing tomato soup on Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) in 2022, someone did it again (with tomato soup, again) at London’s National Gallery, while a few weeks later Picasso’s Motherhood (1901) was pasted over with an image of a distressed mother and child in Gaza.

On the one hand, such protests are having an impact, though maybe not the intended one: the National Gallery has since banned visitors from bringing liquids into the building, while the National Museum Directors’ Council issued a statement saying that such uses of artworks ‘had to stop’. Citizens trust museums, but do museums trust citizens?

It’s worth asking whether the power wielded by such art institutions is largely through the symbolism and weight invested in them as ‘national’ or ‘public’ spaces. Largescale and national museums are increasingly precarious, underfunded while stretched trying to tackle a broad range of agendas, reliant on donors and funders who can steer the programme. In recent years, larger commercial galleries have been attempting to occupy the terrain that was once the preserve of the museum, as gathering places for culture and history, fudging the line between private and public.

But despite, or even because, of all this, it would seem we still need museums, and the nine museum directors on the list reflect an international set of spaces that, in some cases, embody the more traditional role of canon-making and maintenance, and in others a more open-ended role of nurturing a scene. Many of the directors included here are the public faces of vast organisations, representatives of all the work that goes on in the buildings they oversee, generally not doing any of the actual curating, but acting more like ceos. (Though, of course, there are different styles of CEOs – like the hypemachine Musk type, or the faceless bureaucrat type.) Who is on the list hasn’t really shifted this year; but what’s worth noting is what is happening around them: the artists making use of their museums as hangout spaces, social centres and workshop labs (artists such as Rirkrit Tiravanija), and a swell of curators working beyond their institutions to figure out what the future of the museum might be. Who do you trust?

Thinkers

‘Nothing comes from nothing,’ as Parmenides used to tell anyone who would listen while wandering around the Greek colony of Elea (in what’s now southern Italy) during the sixth and fifth centuries bce. And despite its insistence that it’s all about ‘invention’ and ‘novelty’, the same is true of the ideas that come to permeate contemporary art. Often the ideas – many of which are about power dynamics themselves, from feminist and queer theory to the importance of the more-than-human world to postcolonialism and decolonisation – that artists obsess about today have been filtering through the brickwork that supports academia’s ivory towers, or (more rarely) through the shifting sands of public consciousness for several years beforehand.

That ‘thinkers’ is a separate category here is not to say that anyone not categorised as such does no thinking. Rather, it exists in order to suggest that the people within the category assert their influence through the generation of ideas rather than, say, the production of artworks or of capital. (And you might argue that each of these factors – the production of ideas, of material artworks or of capital – provides a different criterion by which the ‘value’ of art might be judged. With, generally speaking, each one providing a different value result.) The exception to this rule – and there always is one (more often many), if only to prove the folly of creating rules in the first place – might be someone like Fred Moten, a cultural theorist and professor in both the departments of comparative literature and performance studies at New York University, and an ‘artist’ contributing to, for example, this year’s Busan Biennale. Or Legacy Russell, whose influence has been channelled through books such as Glitch Feminism (2020) or this year’s Black Meme, as much as through her work as director of The Kitchen in New York. Or artist Hito Steyerl, who is as influential for her lectures and essays on subjects ranging from AI to identity as she is for the way she expresses those same ideas in the form of artworks.

The bigger point perhaps is that art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The work of prominent anthropologists such as the late David Graeber or James C. Scott (who died earlier this year) or the poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant continues to provide fertile ground for those sowing the seeds of biennial thematics and the artworks that take root within them. Death, however, is the absolute barrier to making it onto this list. Ashes to ashes and all that stuff.

You might argue, of course, that when it comes to human activities, ‘thinking’ is a pursuit of the past. That the rapid development and deployment of AI over the course of the last two years alone has begun to render such cerebral activities quaint if not redundant, and that it is bound to keep doing so at an accelerated pace in the years to come. But the composition of this list isn’t about what’s to come; rather it’s about the here and now. And for now, given the already stated reliance on existing ideas in the world of art, thinking is still generally the preserve of humans, even if a growing number of human thinkers are ready to attribute forms of thinking to the more-than-human world (of animals, minerals and machines) – as the number of prominently exhibited artworks that work with entities from these categories can attest.

In a year in which the value of art in purely economic terms has generally declined, you might think that it’s natural for a magazine such as ArtReview to turn to the value of the ideas and thoughts behind artworks as more reliable measures of the field’s relevance to society as a whole. Yet the one doesn’t necessarily follow the other. Because they are not necessarily linked. It might be better yet to consider that the rise of populist authoritarianism, across the globe, makes the spaces in which some form of free or alternative thinking is possible – or, better yet, permitted – more valuable than ever. This, in turn, might be one reason why people such as American academic Saidiya Hartman (best known for her work in the field of African-American studies), Cameroonian political theorist and historian Achille Mbembe (a piercing critic of colonialism and its aftereffects) or anthropologist Anna L. Tsing (best known for her work on the ethnology of mushrooms and transdisciplinary approaches to the understanding of the Anthropocene) feature highly on this list; each of them, in different ways, demands a reimagining of the past so that we might reseed our individual and collective futures. On the other hand, you might consider those perpetuating the oppression of free thought more powerful still.

Explore the 2024 Power 100 list in full