A queer pioneer of experimental cinema, an occultist and lover of pop culture, Anger was unapologetically provocative in his life and politics

Few people present a better case for separating the art from the artist than Kenneth Anger. He was a man of intense contradictions, having become a legend long before his death this month aged ninety-six. He claimed to have retired from filmmaking in 1999, having not made anything since the 1970s, and yet made 14 works in the 21st century. Born into a middle-class Presbyterian family in California in 1927, he rejected Christianity aged eight when his parents tried to make him go to Sunday school and became a pagan. He started making films when he was ten, using his family’s 16mm camera, although he said in 1967 that he had destroyed his early works. Anger was a huge influence on North American and European underground film, as well as directors who crossed over into the mainstream such as David Lynch and Martin Scorsese.

Besides the output that influenced a generation of filmmakers, many projects went unfinished or unrealised because he spent their budgets elsewhere, and his legendary book Hollywood Babylon (1959), written to dig Anger out of a financial hole, was full of scurrilous, unsubstantiated gossip, much of which was later disproved. He was upfront about his homosexuality before the US began to decriminalise same-sex activity, being charged with obscenity for his early film Fireworks (1947); he made works full of Nazi iconography and claimed to be “somewhere to the right of the KKK” on Black people. He was a countercultural figurehead, who worked with everyone from Alfred Kinsey, Jean Cocteau and Mick Jagger to Manson Family associate Bobby Beausoleil, even after Beausoleil was imprisoned for the murder of Gary Hinman. It seems essential not just to separate art and artist – never simple, but especially not with such idiosyncratic films as Anger’s – but also to take a selective approach to the work.

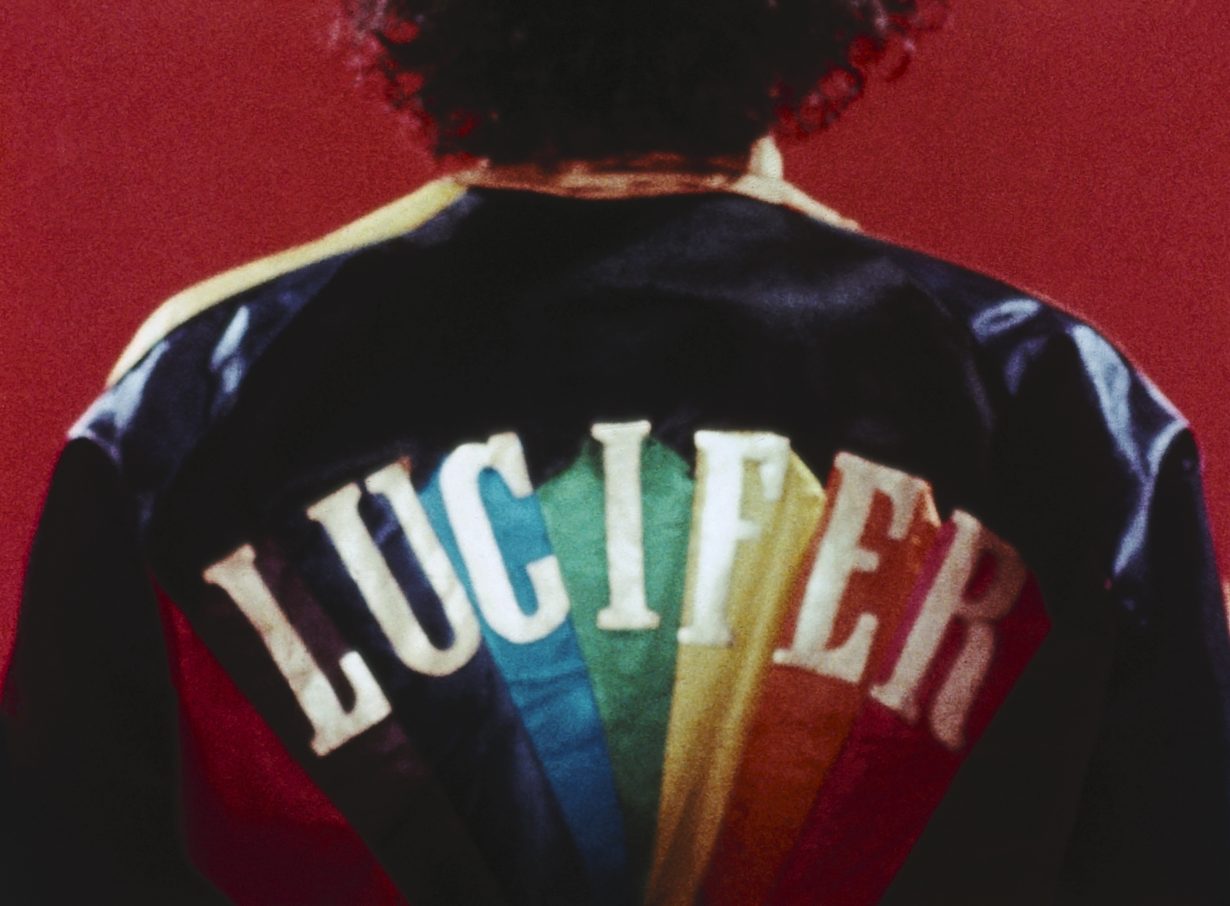

Anger’s surviving films can be divided into three stages. First, the early works, from Fireworks to Eaux d’artifice (1953). These flit from an eerie use of black and white and silent film aesthetics, notably in the magnificent Rabbit’s Moon (1950), about a clown who longs to catch the moon, to the non-narrative Puce Moment (1949), a fragment from a planned feature on Hollywood in the 1920s, with a pop soundtrack that anticipated the music video, and clearly influenced Lynch’s use of vivid primary colours. Second, the cycle for which Anger is best known: the works influenced by English occult writer and philosopher Aleister Crowley, from the 38-minute Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) to Lucifer Rising (1972-80), to which he failed to make a sequel and then retired; and finally, his prolific comeback in the 2000s.

The early films are astonishing, making Anger stand out (alongside Maya Deren) in the emerging US avant-garde. Anger uses his incredible knowledge of interwar experimental film to make utterly unique shorts, drawing from the Surrealists’ use of dream logic and the aloof, sacrilegious strangeness of Alla Nazimova’s Salomé (1923) and J. S. Watson and Melville Webber’s Lot in Sodom (1933). The dreamlike Fireworks, which moves between a bedroom, a bathroom and a black space, is even more forthright in its sadomasochistic homosexuality: sailors beat up and beat off onto a man (with milk poured over him, standing in for semen) before one lights a Roman candle over his crotch. This powerful imagery paved the way for the 1960s queer underground – Ken Jacobs, Ron Rice and Jack Smith, as well as Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey – and established Anger as a brave, brilliant new voice in North American filmmaking.

Anger’s next film, The Love That Whirls (1949) was destroyed by technicians who deemed its depiction of a nude Aztec sacrifice obscene; from then on, many projects were frustrated by forms of censorship, lack of money, or his erratic personality. His planned film on Crowley, The Wickedest Man in the World, was just one that didn’t come off, but this occult period was still highly productive. These films made no attempt to explain the philosophy behind them, and little to convert their audiences, except through highly seductive imagery, montage that drew from Sergei Eisenstein and D. W. Griffith, and music. Anger’s pioneering use of pop songs in Scorpio Rising (1963), which filmmakers had avoided due to copyright issues, quickly became the industry standard.

Scorpio Rising is perhaps the emblematic Anger film, despite being a documentary of sorts. Deeply homoerotic, it follows New York bikers on a night out. Marlon Brando and James Dean feature as the bikers’ heroes; the soundtrack includes Elvis Presley, and Bobby Vinton’s ‘Blue Velvet’. A massive influence over subsequent avant-garde filmmaking, from Jeff Keen to the Cinema of Transgression movement, it cuts rapidly from the bikers to provocative images of Christ, occult symbols, and shots of Hitler and Nazi flags. Anger takes no position on their actions or beliefs, but I read Scorpio Rising as a film about the death drive, and how the bikers’ repressed sexuality leads them down dark paths, with their misplaced desire for conformity. (It’s worth noting the US Nazi Party hated the film, asking the Los Angeles police to investigate Anger for obscenity.) This idea was developed further in Ich Will (2000), with its uncomfortably ambiguous presentation of Hitler Youth propaganda, its lack of commentary leaving room for viewers – rightly or not – to take it as a kind of endorsement.

Anger’s final films were made long after his importance was established, and his career ended with a reprisal of his signature style in a commercial for Italian fashion house Missoni in 2010, featuring members of the Missoni family dancing and staring at the viewer, enhanced by his customary tinted shots and double-exposures. On his demise, we just have more than sixty years of work, most of which stands up incredibly well, being just as enchanting and intoxicating as when it was first screened. Many of Anger’s films are readily available now online and still screened at independent cinemas, defying his censors and critics, so you can judge for yourself, and it’s well worth the time. For all that his formal techniques have been imitated, from the avant-garde to advertising, there is still nothing else quite like them.