Though the Kenyan capital’s art market might be in its infancy, its community is thriving

Nairobi is a city of opposites. Here hustlers, vendors and the poor masses scrape a living in informal settlements like Kibera, Africa’s largest slum, while elsewhere, in gated communities, you can find some of the most expensive real estate in the region. It’s a rough-and-tumble place, in which colourfully decorated private-hire Matatu minibuses and Boda Boda motorcycle taxis jostle in the streets. But in recent years, it has also emerged as a key hub for contemporary art in East Africa.

Granted, it is not yet on par with other African centres of contemporary art such as Lagos and Cape Town, hampered as it is by a number of issues, including insufficient galleries, schools and spaces to make and show art, as well as a lack of structural support from government. But though the Kenyan capital’s art market might be in its infancy, its community is thriving.

Nairobi is the commercial centre of East Africa and is becoming an ever-more important hub for art in the region with a growing list of contemporary art spaces. These include the influential Circle Art Gallery as well as GoDown Arts Center, Kuona Trust and the One-Off Contemporary Art Gallery, to name a few.

In terms of the art market, Circle Art Gallery has led the way. Since 2013 it has hosted the annual East Africa Art auction, attracting art buyers from across the region. When I attended in spring 2019 it was held in an upscale international hotel in the city, and welcomed an enthusiastic, moneyed crowd vying for the works on sale. In 2020, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the October auction went online, selling 90 percent of its lots and generating sales of $128,182. (The most expensive lot was a painting by the late renowned Ugandan artist Geoffrey Mukasa which sold at $9,600.) Circle Art Gallery has also shown works by artists from the region at FNB Art Joburg (one of the leading contemporary art fairs in Africa), at the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London’s Somerset House and will be present at the 14th edition of Art Dubai later this month.

Where some Kenyan-born artists, such as Wangechi Mutu, have found a global audience by transferring to traditional global art centres, there is a special energy to Nairobi that continues to inspire those who live and work there. These artists include painter Boniface Maina, whose work depicts surrealist figures in abstract fashion, and Michael Soi, one of the best-known Kenyan artists. Soi is widely admired for his unique and often satirical work in which he tackles political issues in Kenya such as its relationship with China – in his China Loves Africa series (2012-13) – a collection of colourful works on canvas in which he picks apart the confounding, complex and at times neocolonial relationship that the Asian giant has with many African countries. And he also draws huge inspiration from Nairobi, a city in which he works and that feeds his practice through the everyday interactions he has there.

But a new generation of home-grown talent is also finding inspiration in the chaos and contradiction of the city. “I can’t extract myself from the city. I was born in this place”, says one such artist, twenty-four-year-old Lincoln Mwangi.

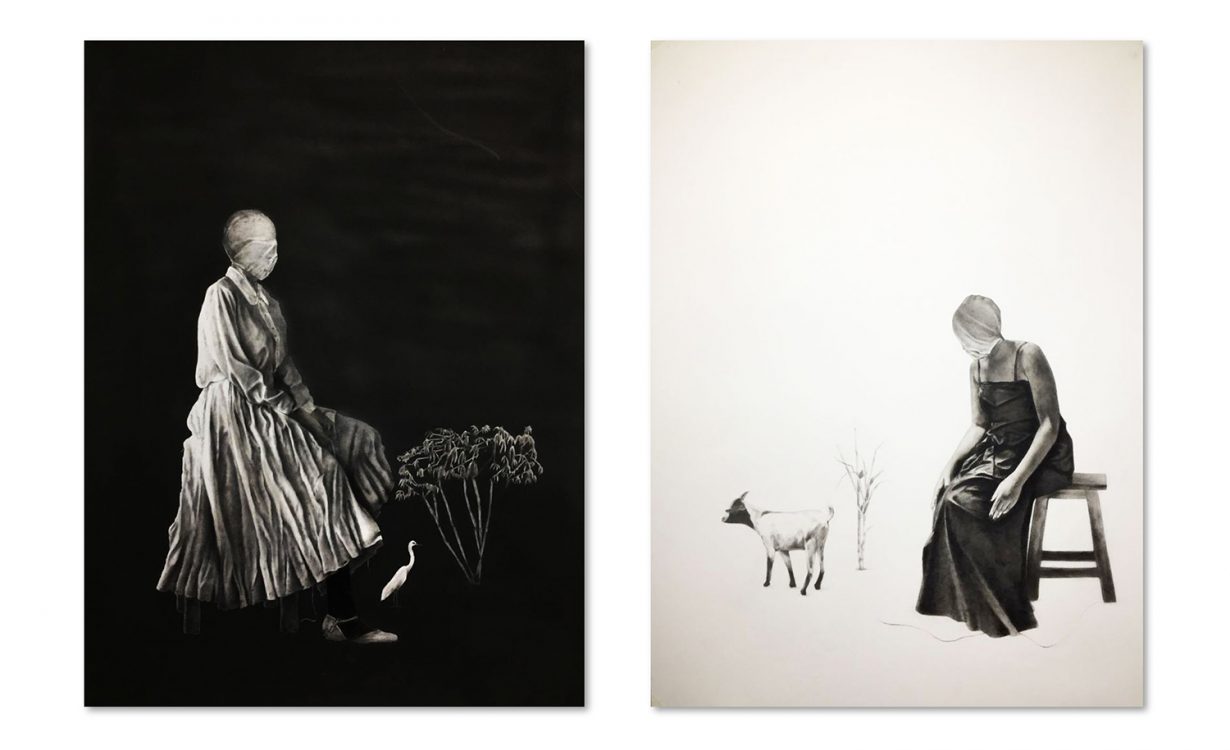

When we talk on the phone, he tackles topics as wide-ranging as Vermeer, CIA water-boarding and why he’s obsessed with Kenyan goats, a subject he revisits in his work as an ubiquitous ‘archetypal’ image of Kenyan life. He does so, he says, because he wants to depict the traditional reality of a country in which 72 percent of people still live in rural areas. Mwangi studied drawing and painting at the Buruburu Institute of Fine Arts Nairobi and is a member of the contemporary artist collective Brush Tu Art Studios – founded in 2013 – which provides artists with studio space, facilitates artistic collaborations and runs open studios for the public. His work explores themes of identity, fear and belonging in an ever-changing city.

He is inspired by the city’s mayhem. “I’ve grown up in Nairobi, there’s a lot of chaos”. He finds beauty in the city and “hope” even as the urban sprawl grows with ever more people, traffic jams and the endless hum of construction noise. But, he says, he also wants to “tone down the chaos”.

His work is presented in figurative forms and portraits of subjects featuring wet cloths and veils over their heads. He calls these figures “avatars” and “shadows” of Kenyan life – a lens through which to capture the inner world of Nairobians. He says the use of cloths and veils in his work has the effect of turning the viewer’s focus to the characters and storyline in the artwork, rather than identities. And given how boisterous Nairobi can be, Mwangi’s work is a meditative attempt to bring a certain quietness in visual form to distil the changing contours of the city.

But artists are inspired not only by the city’s chaos but also by its multicultural tapestry says Verónica Paradinas Duro, a Spanish curator and owner of the online-gallery GravitArt that also runs pop-up shows and which will be showing Mwangi’s work in a solo exhibition titled A Painted Book of Life, Time and Feelings in April. She says what makes Nairobi such an art magnet is that it is “one of the most cosmopolitan and multicultural cities in East Africa”. In keeping with that, it has drawn artists from countries such Sudan, Ethiopia, and Uganda. In a region dominated by autocratic regimes Kenya is more open than its neighbours, even though the country has a bad record on corruption and a history of, at times, violent contested elections. Still, there’s an openness here that affords artists the space and freedom to do their work.

One such artist is the renowned Sudanese artist Eltayeb Dawelbait who has carved out a unique space in Nairobi’s art scene from his studio in the Westlands district of the city. In Sudan, he says “there was no market for us”. He told me there were no room for artistic creativity in his homeland, no space to make and show art and that coming to Nairobi gave him the opportunity to develop his craft within a bigger artistic community. Dawelbait is one of a generation of artists who left Sudan to find artistic freedom outside the regime of former dictator Omar al-Bashir.

His work is known for its inventive use of materials such as wood, recycled doors and windows – he’s also inspired by billboard advertising in Nairobi (where he has lived for the past 15 years). He makes his own paints using natural ingredients and he spends endless days searching throughout the city for materials to recycle into his art, such as for his piece, Encounter (2019): a mixed media work on wood, composed of two pieces each depicting a male and female figure on wooden doors the artist found in Nairobi.

Dawelbait’s work is inspired by his Sudanese childhood. His father was a navigator: astronomy, the desert and sky of Sudan have had a lifelong impact on his imagination. In recent years, though, he’s focused on portraits of the people he encounters in his everyday life in Nairobi, as well as resurrection in the found and worn objects he finds in its streets. He sees his work, as it reveals hidden layers of the city, as reimagining its history.

Azza Satti a Sudanese-Somali creative director at Statement Films, a Nairobi-based female-led film company that supports African women filmmakers, says that Nairobi has now become a “cultural destination”, its artworld fizzing with a creative buzz. The art capital of East Africa needs serious care and investment if its cultural scene is to further thrive: both through supporting the artistic infrastructure in the city, and fostering an appreciation for contemporary art among its inhabitants. But it is clear that the rise of art in Nairobi is symptomatic of a significant cultural shift, in which creatives of all stripes are finding new opportunities, despite the difficulties they face.