For decades the artist-duo have used the motto ‘Art for All’ as their mission statement. As they open their new centre in London, where does this approach sit alongside their actual politics?

I’ve never known what to make of self-proclaimed ‘living sculptures’ Gilbert & George. Their impeccable tweed suits and unwavering togetherness – they have lived and worked as a pair since meeting at Central Saint Martins in 1967 – have made them unlikely gay icons, even though they don’t publicly discuss the nature of their domestic relationship (they reportedly entered a civil partnership in 2008). Their insistent use of the Union Jack as a motif of their work, combined with their open admiration for Boris Johnson, have made them the artistic voice of the Brexit era, yet one half of the duo – Gilbert Prousch – was born and raised in Italy. Seriously though, what is their deal? Over the years, as I routinely saw them walking up and down Kingsland Road in Dalston, London – where they famously dine daily at the same Turkish grill restaurant – I entertained the idea that they were radical pranksters whose ambiguous nature was a mere façade, a queer strategy of diversion. After all, they came of age at a time when being labelled as gay artists could end their careers – concealment was part of the act. But visiting the Gilbert & George Centre, their new permanent exhibition space in London’s East End, has left me feeling that they might just be as conservative as they appear.

Tucked away in a pebbled courtyard on Spitalfields’s Heneage Street – a stone’s throw from the artists’ home studio on Fournier Street – the centre boasts three large exhibition spaces over separate floors. Housed in a nineteenth-century brewery, converted by the local firm SIRS architects in collaboration with Gilbert & George, it is very much in the artists’ image: quaint, quirky and, well, quintessentially British. From the street, visitors are greeted by an art-nouveau-inspired green iron gate whose hand-forged whiplash lines form the G & G. The gate is adorned by King Charles III’s gold-encrusted royal cypher – you guessed it: a testament to their affection for the monarchy. Inside the courtyard, past the reception area, a beautiful Himalayan magnolia tree leads the way to the exhibition space’s entrance.

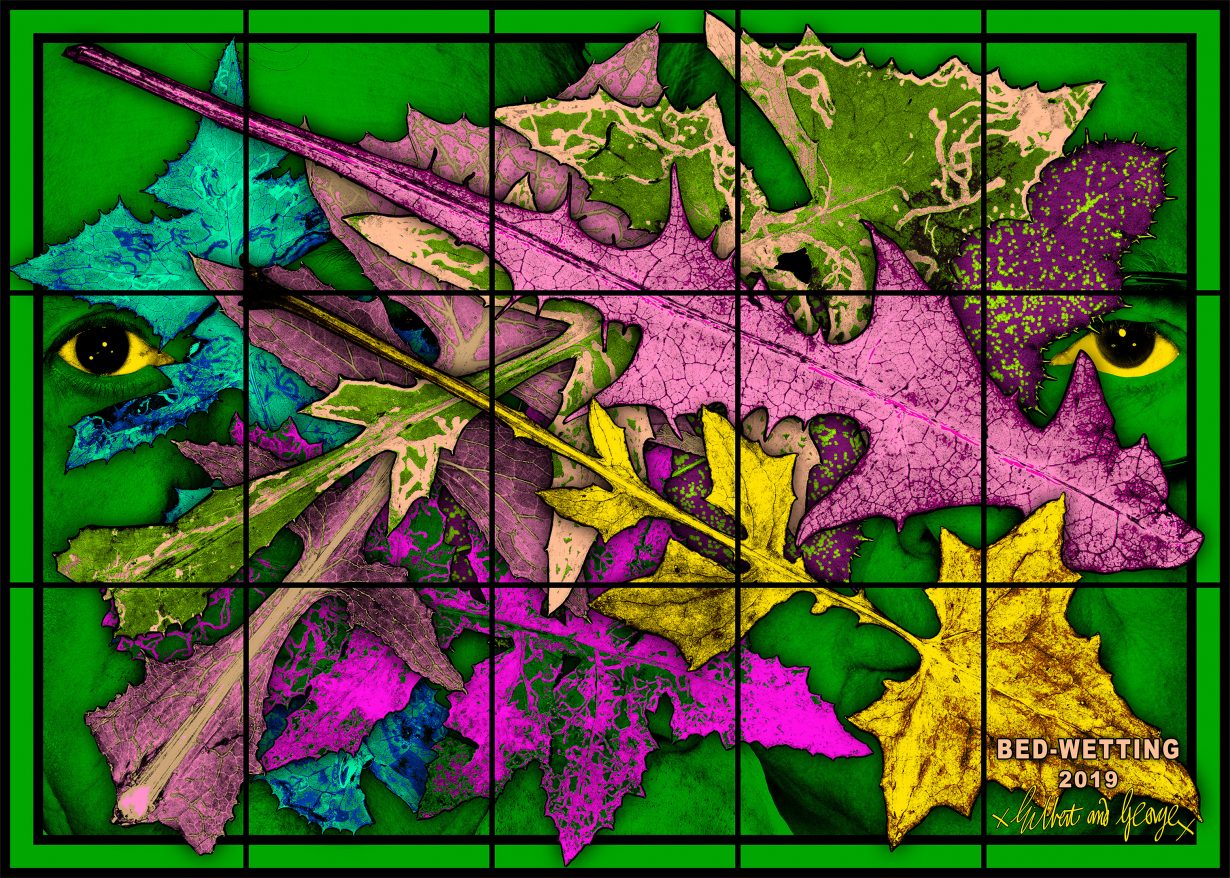

The inaugural exhibition, THE PARADISICAL PICTURES, comprises 35 of their signature largescale photographic montages from 2019. Across all three floors, the works incorporate self-portraits, texts and vegetal motifs, depicting comical visions of a heavenly world punctuated by anthropomorphic chains, spiral telephone cords and floating desert boots. Of all the works I’ve seen by Gilbert & George, this series appears particularly refreshing. Vibrant colours combine with abundant vegetation punctuated by floating eyes – suggesting the presence of wild creatures – to imbue works such as BED-WETTING, LION TEETH or EATEN MESS with a fantastical quality reminiscent of nineteenth-century Naïve painter Henri Rousseau. In other pictures, the artists – who often appear in their own work – are subjected to metaphysical transformations, their heads morphing into dates, stones or magnolias.

As I walk down to the lower gallery, however, my enthusiasm deflates. There, a lively picture featuring similarly turquoise and magenta foliage surrounded by two sets of eyes and oversized dates is inscribed with DATE RAPE in capital letters. The pun isn’t particularly clever, let alone funny, and exuded a whiff of poor taste that contaminated the rest of the show. Of course, Gilbert & George are no strangers to controversies. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, works like PAKI (1978), depicting a South Asian man sandwiched by the suited artists, or PATRIOTS (1980) and FOUR KNIGHTS (1980), which ambiguously glamourised young skinheads, raised some eyebrows. During a brief conversation, the artists (who upon learning of my Belgian origin compliment me on our great king and delicious horsemeat) say this recent series was inspired by the natural world’s presumed mischievous behaviours – the “sexual orgies of the plants”, in Gilbert’s words. That’s all well and good, but the casual insertion of rape seems a gratuitous shock tactic that is best left to the twentieth century.

Throughout their career, Gilbert & George (now aged 79 and 81 respectively) have used the motto ‘Art for All’ as their mission statement. It often appears in their work but also in their marketing and promotional materials, supposedly to assert an anti-elitist agenda. It’s a curious claim for horse-eating, Thatcher-loving monarchists, one whose deeper subversive meaning I no longer expect to find. And while the centre graciously welcomes its visitors free of charge, those who feel alienated by the perpetuation of grand nationalist narratives, and the dubious humour that stems from them, may find that its sole focus – the art of Gilbert & George – isn’t for them after all.

THE PARADISICAL PICTURES at The Gilbert & George Centre, opens 1 April 2023