Grotesquerie has long been the language of rebellion. On our screens and in the contemporary art gallery, an era of ugly, morbidly playful satire is back

The most recent season of South Park follows a now well-trodden storyline whereby Donald Trump has (anally) impregnated Satan. The US president’s destruction of the White House East Wing is interrupted by a scheme to murder the unborn “butt baby”. Listening to the South Park J.D. Vance’s strange, lilting voice – an accent somewhere between Austin Powers’s Dr Evil and mid-century detective Poirot – provides a sense of relieving unreality. In a parallel sub-plot, the children of South Park launch a digital community lamenting the moral decay of their town and platform their digital currency: “South Park Sucks Now Bitcoin”. Reality is reflected as if in a warped carnival mirror. In South Park, grotesque satire is par for the course: a form of didactic subversion marked by distended forms, the debasement of hierarchy, and revelry in the lowest strata of culture. Its rebellion against tyranny is, unfortunately, one of the few examples left.

Which brings me to Now We Are On Easy Street, an exhibition by Marc Kokopeli which ran at Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, and ushered the American sitcom into the lexicon of fine art. The stripped-back carcasses of South Park’s forever youth of Eric Cartman, Kyle Broflovski, and Stan Marsh stood in four separate vitrines. Without their signature primary-coloured winter clothing, their forms manage to conveyed the bare bones of satire. Built into three-dimensional soft toys and clothed in outfits sewn and constructed by the artist, the characters’ changing expressions and a theatrical backdrop were shown on a transparent LCD screen which fronts a metre-long LED vitrine containing (imprisoning) the toys. The White House’s most recent crusade on the TV show derided ‘the left’s lack of authentic or original content causes them to gravitate toward low-brow television’. Kokopeli, for his part, believes its characters should be enshrined in two large-scale rectangular playsets.

Just as Sigmar Polke once used cartoonish painting to mock the state’s handling of Red Army Faction deaths (Untitled [Dr Bonn], 1978), Kokopeli uses popular imagery to test how such symbols of the grotesque survive an artist’s dissection. Trapped behind glass, the characters perform an unnerving, self-reflexive script that diverges from the show’s own vulgar tongue. They instead echo the stilted tone of Kokopeli’s previous video work, which appropriates his mother’s educational movies from the 1990s.

“This low-rate TV I’m living in is called **** OMG. I’m a nine-year-old fourth grader who went from country girl to city girl.”

“I needed to talk to someone about my life crisis. Thanks for listening”.

“Oh…okay…sorry if I talk too much”.

“What is up with this TV?”

The playsets Kokopeli constructs to house his characters stem from a sense of apathy. He removes them from their fixed roles, giving them new scripts and costumes he has sewn himself. Their surreal backdrop (an entirely red room, or the ball drop in Times Square at New Year’s) once again communicates the versatility of these characters as vessels for projected meaning. As politics becomes increasingly facile, and Trump’s aesthetic delves into the realms of the fantastical, re-hashing symbols of tradition, as per Umberto Eco’s ‘Ur-fascism,’ Kokopeli builds toys scaled for oversized children.

What Kokopeli understands is that grotesquerie has long been the language of rebellion. In Rabelais and His World, the Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin defines grotesque realism as that which celebrates the bodily principle – the laughing, eating, shitting, birthing body that degrades the lofty and renews the world. Taking the five texts of Renaissance writer Francois Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532) as his source, Bakhtin argues that laughter is humanity’s greatest tool of dissent and only worthwhile form of rebellion. Rabelais’s is a boundless world of humorous forms and manifestations found in the medieval carnival, which stood in stark opposition to the serious and courtly tone of medieval ecclesiastical and feudal culture. In the pentalogy’s first book, Gargantua’s mare drowns part of an army in her urine, and, at another point, a woman is impregnated by the shadow of a large phallic belfry tower. For Bakhtin, Rabelaisian degradation is generative: protean forces are elevated in the face of sterility, immovability or hierarchy.

If Bakthin’s framework is dated – it’s not like we are unused to extremity today; from AI-generated visuals of a rebuilt Gaza to meme replications of Charlie Kirk’s assassination – his insistence on a morbid kind of laughter’s political force remains true. Satirical extremity in visual culture is, now, all-encompassing and hugely online: the carnival has moved into the digital, and legacy media can’t keep up. Shows such as South Park can be put together in a week, allowing it to parallel the currency of meme production while building on decade-old callbacks (Kenny’s repeated death and subsequent consumption by rats is indeed very Rabelaisian).

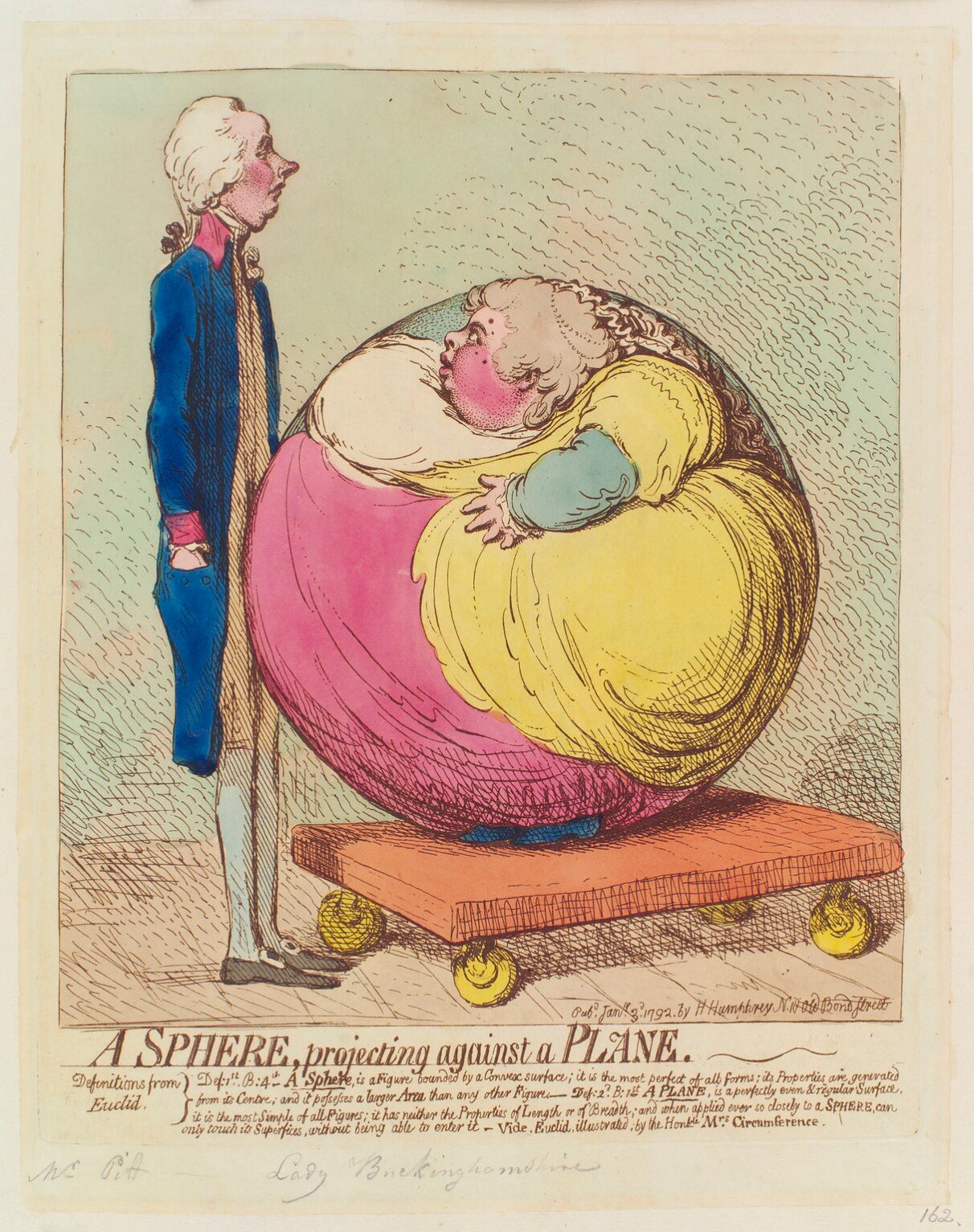

The grotesque body, as Bakhtin understands it, is always in flux: full of holes and orifices, it refutes the smooth, closed ideal of Renaissance form. It is a dialogical body, always in motion. There is a direct line from Rabelais to James Gillray’s eighteenth century caricatures, where distorted proportions render the absurd imagination legible. Much has been said of the role of memetic currency in shifting elections, popular voters and the youth. But South Park, a TV show originally aired in 1997, both pre-dates and surpasses new media. The show’s rotund cast has become the mascots of a self-proclaimed status as ‘equal-opportunity offenders’. Indeed, the political ambivalence of the grotesque is reflected the political flip-flopping of the show itself. The show’s genius lies in its apathy: having for years mocked the “Woke Left”, its approach now is to dismantle the mainstream by upping the ante against Trump. South Park’s creators have remarked that “It’s not that we got all political, it’s that politics became pop culture”. Then they laugh their way to the bar after a $1.5 billion dollar deal with Paramount for the streaming rights to their animated content.

Recent contemporary art, it seems, is capitalising on the versatility of the cartoon to politically undermine the institution (be it art, political, or otherwise). Take Cosima von Bonin’s current show at London’s Raven Row, where plushie toys and inscriptions of New Yorker cartoons onto canvas carry a Polkian ‘fuck-you’ to art speak, minimalism and the German art establishment. Works like Thrown Out of Drama School echo the tongue-in-cheek tone of Kokopeli’s Literature & Painting Playset, which sees two South-Park plushies dressed respectively as a preaching puritan and a discombobulated, struggling artist. Similarly, early 2010’s postinternet art like Paul McCarthy’s fairytale series (White Snow Dwarf Bashful, 2010) and Jordan Wolfson’s Coloured Sculpture (2016) have a post-reccession cynicnism that sees the perversion of two beloved D*sney cartoons. There is, again, something Rabelaisian about the male artist creating full-bodied figurative sculpture of childhood cartoons dripped-out with dildos.

More recent works like Paul Fritz and Virginie Sistek’s My Wife Read Novels, I haven’t got the time (2024) recall the animation of early 00s straight-to-DVD kids films, a style that is now resolutely out of fashion, and carries with it the taste of redundancy. Urs Fischer enacts a more conceptual satire in his Chumbox series. His oil paintings directly imitate the thumbnails of internet spam pages, where small, highly saturated images are accompanied by texts such as ‘Old Man Got Ripped Fast With One Small Trick’ to disrupt his painting show Easy Solutions & Problems (2025). The puppetlike movements of Kokopeli’s Playsets read like a Punch and Judy show conducted for a Gen-Alpha audience. Fischer, like Kokopeli, inverts the gamified language of our visual culture, creating artworks that function equally as playthings. If Rabelaisian play always followed Shrovetide observance (per Bakhtin), we now venerate the popular potential of nine-year-old boys Cartman and Kyle as the world turns grey, and terror is conquered by laughter.

Read next Carol Rama’s grotesque, ungovernable iconography finds the limelight