Can the much-delayed edition – forged over the protracted disruptions of the pandemic – deliver on its promise of longterm thinking?

One evening in September, in the amphitheatre of the Santralistanbul arts complex, I watched a performance by Bread and Puppet Theater. The venerable American troupe stages dramas that invoke mythical, messianic visions (their performances over the past six decades have doubled up variously as demonstrations against the Vietnam War or the avarice of Wall Street). Here, it consisted of enormous papier-mâché serpents, flag-toting stilt-walkers and chanted nursery rhymes – a near-constant cacophony (by turns engrossing and boring) that was only stilled by the arrival of the evening call to prayer wafting over rooftops. Later in the week, I observed (with a strange feeling of detachment) the Indonesian artist Arahmaiani conduct a crude flag-waving ritual; each banner marked with a Turkish word, for ‘rebellion’, or for ‘love’. Looking back on this year’s Istanbul Biennial, and its enthusiastic homespun parades, ritual and ceremony, I wondered: what good, in the end, is such pageantry?

The biennial’s untitled 17th edition ostensibly seeks to articulate a turn to longterm thinking and a concern for local communities. ‘Rather than a great tree, laden with sweet, ripe fruit, this biennial seeks to learn from the birds’ flight, from the once teeming seas, from the earth’s slow chemistry of renewal and nourishment,’ Ute Meta Bauer, Amar Kanwar and David Teh write in their melodious curatorial statement. ‘Let this biennial be compost. It may begin before it is to begin and continue well after it is over.’ Fittingly for an exhibition that held its opening reception in a medicinal garden, fragrant with kaffir lime and Chinese ginger – and in which the artist Laura Anderson Barbata had hung a set of crimson hammocks made by Yucatán weavers – this motif of rich fertiliser is an invitation to mount artworks that, in parts, gestured towards a set of folkish politics.

These took the form of micro-utopias – spaces which not only promise to be bastions against all that is bad in the world, but stage rehearsals for a better world to come. For instance, the printing of a special newspaper titled Dumpling Post; at its launch event, guests gorged on delicious lamb-filled manti. The conception of the publication (filled with articles that unravel the connections between food and politics) dates back to 2019, when Istanbul’s Hrant Drink Foundation – the civil-society organisation founded in memory of the murdered journalist – was banned from holding a conference on political history. In response, the foundation’s staff insisted on their right to open dialogue; they went shopping for flour, butter, rolling pins, scoured the area for specialist chefs, and held a ‘Dumpling Festival’ instead. Elsewhere in the city, the artist duo Cooking Sections have opened a traditional milk-pudding shop, selling exquisitely rich custards – purportedly to draw attention to the unlucky water buffalo whose wetlands on the outskirts of Istanbul are shrinking ever further in the face of the encroaching capital. (I am probably far from the first to observe that the biennial’s main sponsor, Turkey’s biggest industrial conglomerate, has played its own part in Istanbul’s rampant processes of urbanisation and gentrification).

The city, this exhibition appears to say, has its own, secret stories to tell. Installed within the sixteenth-century Çinili Hamam, is Taloi Havini’s installation Answer to the Call (2021) which brings the sound of sonar mapping with sacral flutes and chanting into a call-and-response score. And yet it’s the architecture of the Ottoman bathhouse, transformed into a chamber filled with chiming tones and crashing ambience, which plays the starring role. Similarly, the artist Tarek Atoui uses the cavernous resonances of another historical bathhouse, the Küçük Mustafa Paşa Hamamı, to create a soundscape that draws our attention to the creation and processing of sound itself. In Whispering Playground (2022) he runs workshops instructing children in the haptic, sensual qualities of noise and music by playing them field recordings of Istanbul’s busy shipyards, and then filtering the sounds – via underwater microphones – through pails and basins filled with water.

Striking a more disturbing note, beneath Gezi Park lies a disused metro tunnel more than 250 metres long: here, Carlos Casas has installed his bone-shattering work Cyclope (2022), which manipulates elongated, mysterious noises (his many undisclosed sources include experiments derived from sound torture), into a vast, upsetting experience. Gentler is Evrim Kavcar and Elif Öner’s Dictionary of Sensitive Sounds (2022), an installation at the Performistanbul space, which draws a map of the ‘in-between sounds’ of daily life. These sounds-as-memory-capsules include a clutch of pebbles and coloured glass accompanied by the scrawled note: ‘the sound of swallowing after you’ve been dehydrated for a long time’.

In many cases, however, the spaces housing the works continue to be so intriguing that the art inside them is fated to become undone. It isn’t long, at the Pera – host to an installation by the artists Irwan Ahmett and Tita Salina, studded with samples of dry lava, which appears to offer a sociopolitical history of volcanic eruptions in Java; Lida Abdul’s video In Transit (2008) in which Afghan children stuff an abandoned military plane with cotton and pretend to fly it like a kite; and a droning performance by Sriwhana Spong in which dancers ring a collection of bronze orbs like bells – before I’m wandering downstairs to inspect the museum’s magnificent collection of Ottoman coffee cups.

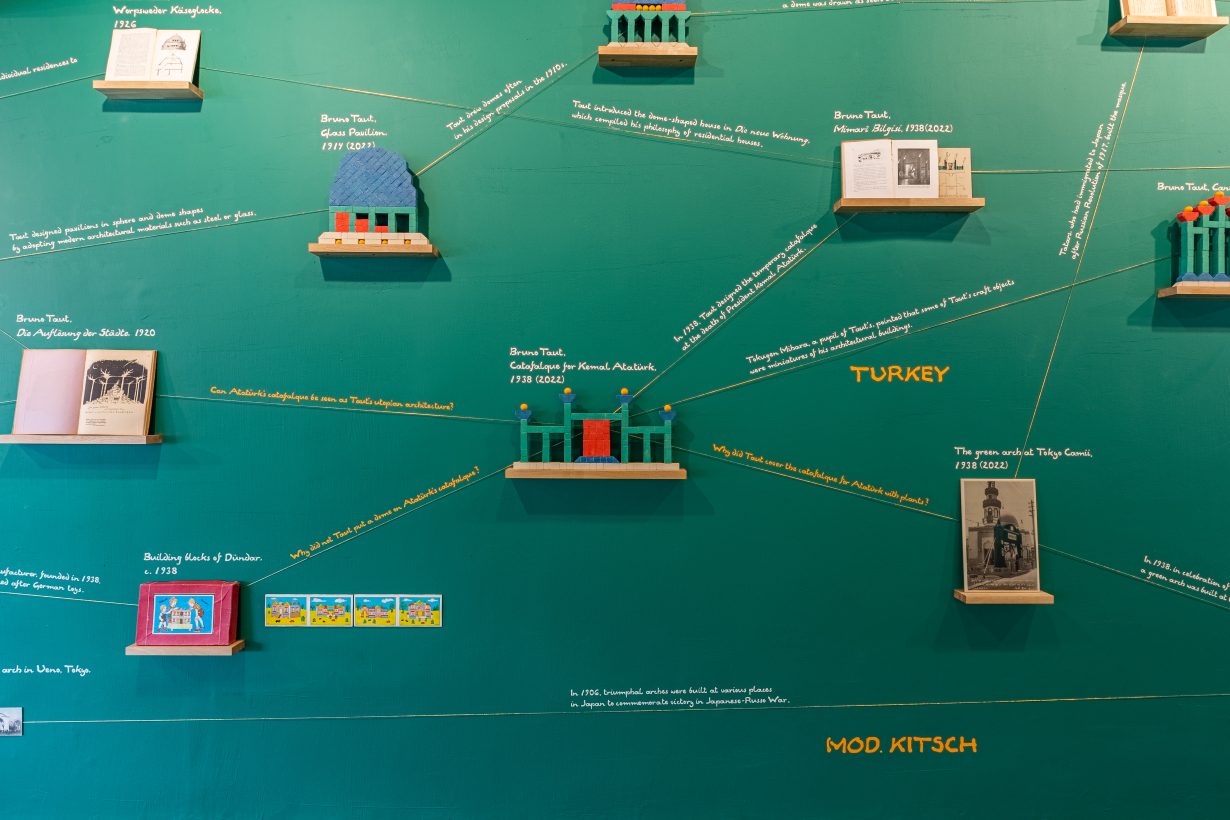

At Barın Han, the former atelier of one of Istanbul’s famed calligraphers, Nakamura Yuta’s study of the utopian roots of modernist architecture in Turkey – presented as a detective’s evidence board – is compelling enough. But after viewing the lacklustre archival displays that comprise the rest of the artworks on show, I spend the remaining time admiring said calligrapher’s impressive bookbinding paraphernalia instead. Meanwhile curator Marco Scotini’s Disobedience Archive (2005–), a touring video library that documents our age of explosive protest movements, is completely overshadowed by its haunting setting: an abandoned high-school whose classrooms have remained untouched for the past two decades.

The high-minded mood continues at the Müze Gazhane, a former gasworks-turned-museum, where I watched INTERPRT’s Mining the Abyss (2022), an investigation into the destruction of marine biodiversity by deep-sea mining. I lingered around Orkan Telhan’s The Museum of Digestion (2022), a kind of deconstructed garden comprising mint, cow dung and ants, accompanied by a book for which human researchers were ‘interviewed’ by the cow dung. (And I got to watch the unedifying spectacle of an art critic from Vienna – who evidently had not got the memo that this exhibition was supposed to be about patience and mutual vulnerability – bully a baffled exhibition guide over why he had not read said book).

What is all this for? Presumably, a straightforward test of the biennial’s critical framework of ‘composting’ – and all its claims to latitudinal thinking and deep engagement – will be the longterm legacy of its dabbling in exchange and dialogue: what all the music classes, puppet workshops and indie newspapers might mature and grow into over the coming years. Still, I must admit – and especially after looking at yet another solemn little artwork, this time about Eastern Anatolian cheesemaking traditions and good village governance – that all the earnestness was making me feel totally miserable. I don’t, actually, need artists to tell me that a better world is possible. I longed for some whiff of uncertainty, some acknowledgement that the world can be as strange as it can be good and bad. Sometimes, though, art has a way of coming through for you. Taking a turn in some ancient hammam one afternoon, I came across the most striking image of the show, an unframed photograph from Lieko Shiga’s series Human Spring (2019). Two men, heads bowed, sit submerged in an overflowing bath covered in lotus fronds, while gloomy, dappled light filters through the window. It’s a very weird, spooky moment. And it says something about this exhibition that it was the only picture that my mind’s eye wanted to keep turning to days later.

17th Istanbul Biennial

Various locations, Istanbul

17 September – 20 November