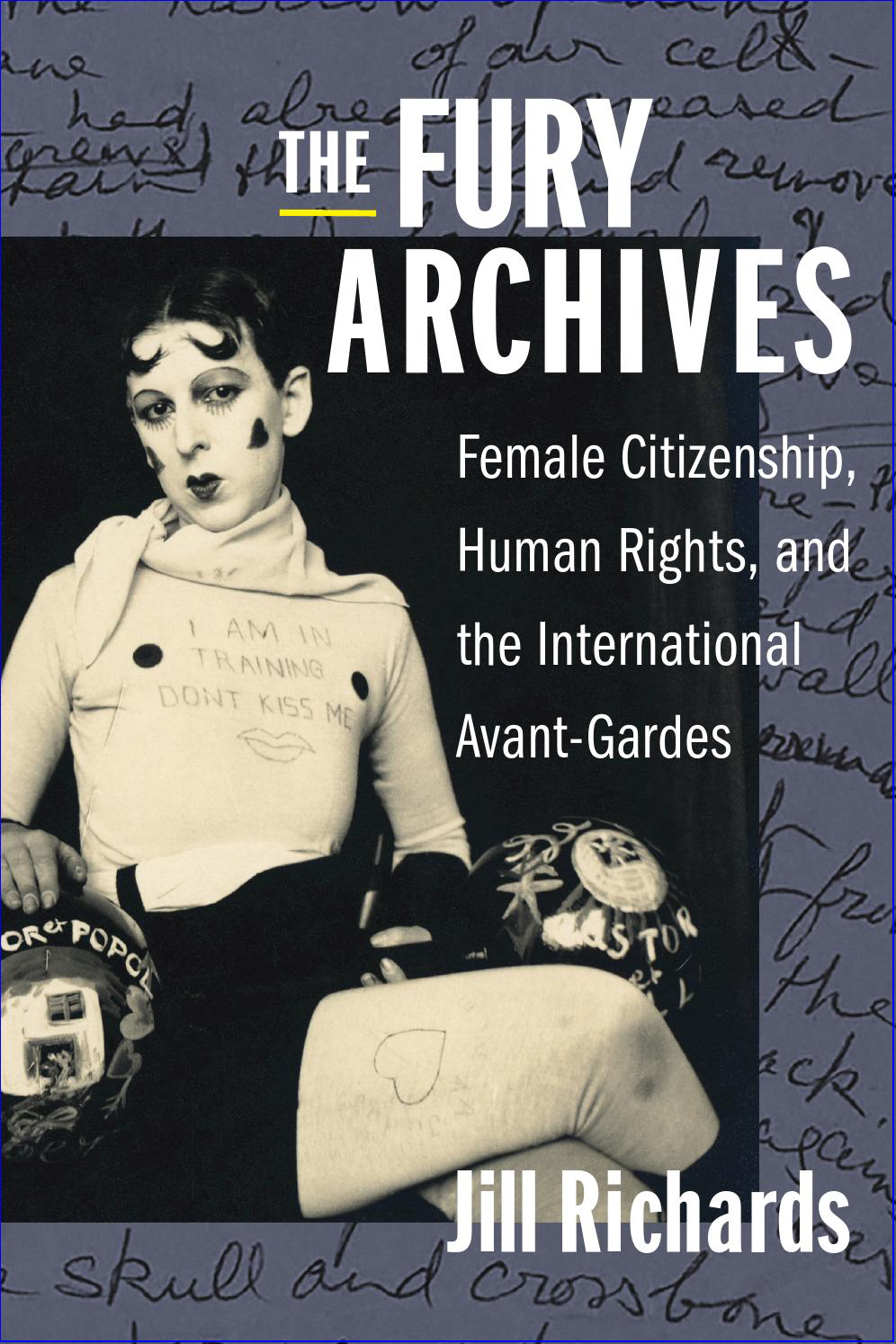

From bildungsroman literature to birth-control pamphlets, Jill Richards’s new study charts the struggles of female citizenship across time

‘The washerwoman Josephine Marchais seemed dirty and withered, though still angry looking, “like a fury.”’ Likening a pétroleuse – women who were put on trial for alleged incendiary activities during the Paris Commune in 1871 – to a fury, the author Léonce Dupont employs physiognomy to pass swift judgment on the five women he encounters at one of the trials in his book La Commune et Ses Auxiliaires Devant la Justice. That women who fight for their rights are stereotyped as manhating, ugly, hysterical, even unnatural is hardly of recent imagination, as Jill Richards’s study The Fury Archives: Female Citizenship, Human Rights, and the International Avant-Gardes (2020) reveals. She uses a wide range of archives to chart the history of modernist women’s struggles for various rights – seeing each movement as both events in themselves and in contact with each other. During the course of this, her book steers away from the specific demands made by each of the selected movements to examine acts of resistance as an extended practice in the day-by-day experiences of the women who were part of these movements.

At first Richards’s selection of archives seems unconventional: she mines bildungsroman literature, schedules and minutes of meetings, little magazines, public petitions, sex manuals, birth-control pamphlets, paintings, photographs, plays, tables of contents and suchlike, all produced by women to chart ‘the lived experiences of female citizenship as a practice and process’. She consults arrest records and prison sentences to record names and stories of women who were part of various movements. In doing so, Richards brings to attention the quotidian nature of politics instead of seeing it as an occasional activity the women indulged in.

The first of three parts in the book examines the afterlives of women incendiaries through the act of naming names employed in Ina Césaire’s intimate 1992 play, Fire’s Daughters. The chief character, Rosanie Soleil, is a historical figure, though the story of the play is not a historical drama. The prologue sees the character of the mother doing housework while an off-stage voice delivers in monologue the names of the women who participated in Martinique’s Southern Insurrection. Their names, ages, professions, places of birth and domiciles are recited, acknowledging their acts, placing them in history. In chapter two of this first part, in what Richards calls the ‘long middle’ of the militant suffragette movement, she reads the everyday lives of the women and the process of the campaigns themselves.

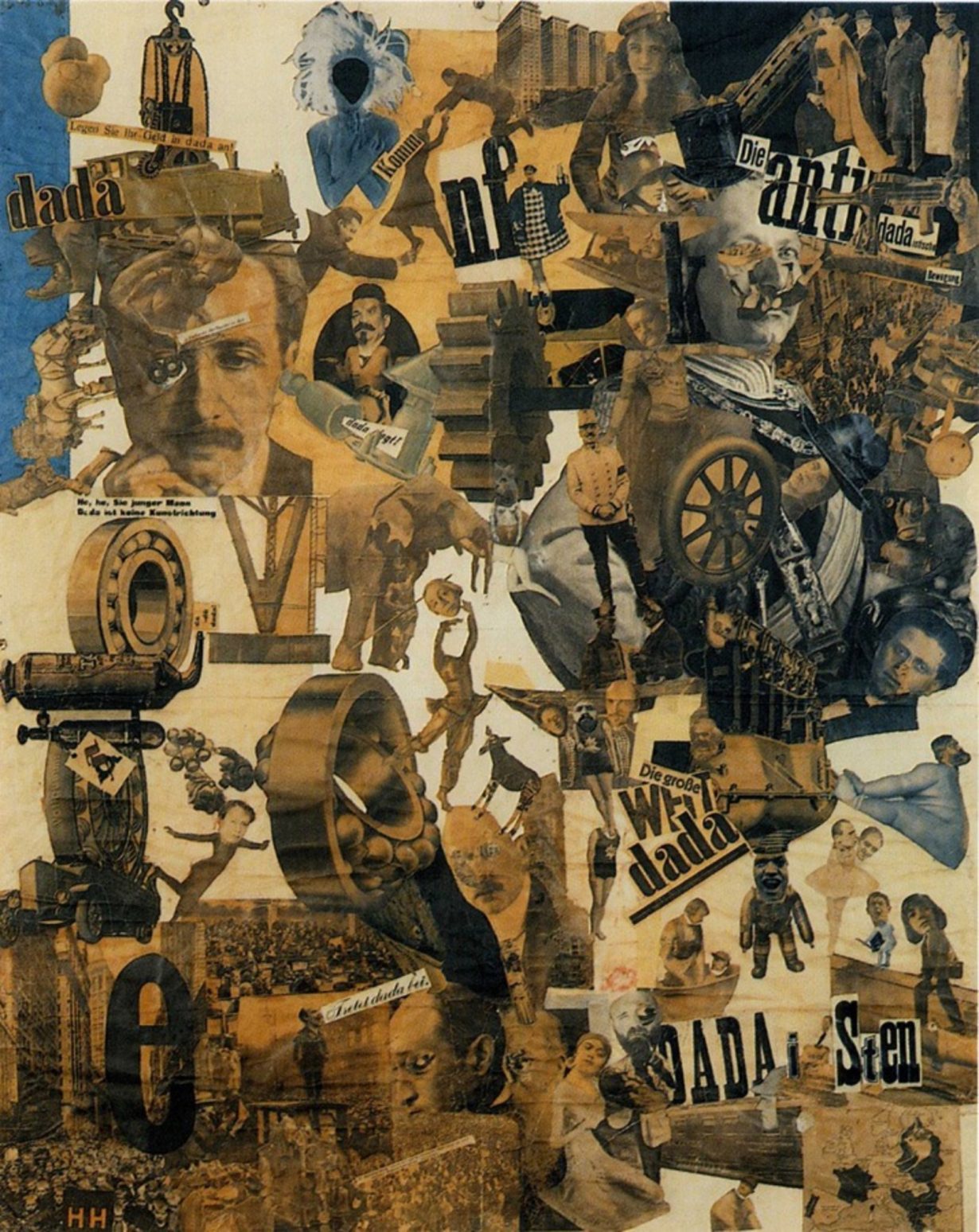

Part two looks at the history of reproductive rights across the Atlantic, via the role little magazines like The Women Rebel (1914) and The Birth Control Review (1917–40) played in the pro-choice movement. Hannah Höch’s art and Mathilda (Til) Brugman’s short story ‘Department Store of Love’ (1931–33) are used to thread the connections between Dadaism and queer feminism movements from the 1920s onward.

Man Ray’s 1922 portrait of Marquise Casati and the works of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore are among the archives that Richards examines for a history of Surrealism’s preoccupation with the female form as a set of identity characteristics and the treatment of queer resistance. In the final part of the book, the form of committee meetings as faulty but foundational to the development of institutional human rights is analysed through the reports and editorials in Paulette Nardal’s journal Woman in the City (1945–51).

The sense of this being a history of the present is hard to ignore. The rights pertaining to citizenship, reproduction, sexuality and suffrage might have been secured through long struggles, but several have become newly vulnerable in the present. Richards clarifies, towards the end, that the book is not meant to be an instruction manual, but admits that the layers she was investigating in The Fury Archives were motivated by the politics of the present. That strategies such as the occupation of public spaces as an act of protest, strikes to try to accelerate governmental action or the naming of names as an act of acknowledgement and remembrance remain familiar and continue to be employed make many of the decades-old archives seem eerily contemporary.

Jill Richards, The Fury Archives: Female Citizenship, Human Rights, and the International Avant-Gardes, 2020, is published by Columbia University Press