There is a common thread of loathing for and criticism of India among Indian writers. Deep-rooted corruption, poverty, the great disparity between the rich and the ordinary, a filthy environment, sexual harassment of women, casteism, untouchability, the pathetic situation in villages where men and women from a particular community work as scavengers cleaning the faecal waste of fellow humans, religious fundamentalism, especially Hindutva – a fascist state of mind that denies diversity and propagates hegemonic unity – the list is neverending. And while these are all real issues that India needs to address, a byproduct of this is that it shapes the lens through which the West perceives Indian society in the current day and age.

In that respect, In Light of India (1995), a book written by a Westerner, the Mexican poet Octavio Paz, is an exception to the rule. Based on his experiences of living in Delhi during the early 1950s and for a longer stretch during the 60s, as a diplomat and ultimately ambassador, it gives incisive insights into facets of India other than its darker sides. So, what does the book highlight? That it is hard or rather impossible to appreciate the country with only a Westerner’s knowledge. India’s unique aspect, Paz writes, is that it is based on a science that stands in total contradistinction to Western thought processes. It may even be incorrect to term it a ‘science’, in the Western sense, at all.

For instance, for any siddhi (attainment), one needs mantra (the energy), yantra (the vehicle) and tantra (the road map). Put another way, siddhi emerges when the raw material (mantra) is fed into the milling machine (yantra) according to a fixed process (tantra). Mantra gives energy to yantra. We call the one who attains siddhi through this process a siddhar.

A siddhar can even become disembodied and enter another, lifeless body, reanimating it. Several siddhars, like Thirumoolar, Adi Shankara (the founder of Advaita philosophy and a yogi who absorbed the teachings of the Buddha into Hinduism) and Arunagirinathar, have experienced this siddhi, called parakaya pravesam (para – other, kaya – body, pravesam – entry). Other siddhis include the power to turn iron into gold (alchemy), to fly, to walk on water and to live eternally.

A Westerner might dismiss all this as mere myth and legend. But it remains the very foundation of India’s philosophical-scientific- spiritual tradition. There are no books, laboratory-based research or experiments, as there would have to be in the modern West, to substantiate this theory. The gurus taught and handed down such techniques to their students orally, mainly to protect their sanctity, and out of fear that ordinary men would misuse them.

The first step on the Indian path of knowledge (jnana) is to undo everything one has learned so far and keep the mind as open as an empty sheet of paper. A book that has brought tremendous transformation to me in this respect is the Aghora trilogy (1986–97), by Robert Svoboda, an American. This trilogy details the life of Svoboda’s mentor the Aghori Vimalananda, a practitioner of the tantric technique called Aghora, which Svoboda learned from Vimalananda; and several of their discussions and experiences over a ten-year period. Before Vimalananda’s death, in 1983, he was known as an unassuming family man and the owner of Thoroughbred racehorses. Only a handful of people close to him knew that he was an Aghori. Vimalananda never cared to reveal this fact, wary of being associated with those fake gurus under whose spell Westerners are prone to fall – gurus offering Kundalini yoga as if it were pizza (and in the process turning themselves into billionaires).

A modern reader of the trilogy might think it a fantasy novel filled with old wives’ tales. Not the reader’s fault, but that is what science has taught them to believe. Svoboda wasn’t one to trust an Indian guru blindly. A licensed Ayurveda practitioner, Svoboda was not an Aghori himself, but during the decade he spent with Vimalananda, he watched and learned from the yogi up close. So I cannot totally dismiss his work as a fairytale. Every Indian comes across many such yogis in their lives, and this presents them with only two choices: either to reject everything, on the basis that it does not conform to the British-imposed Macaulay system of education, or to embrace traditional Indian modes of thought.

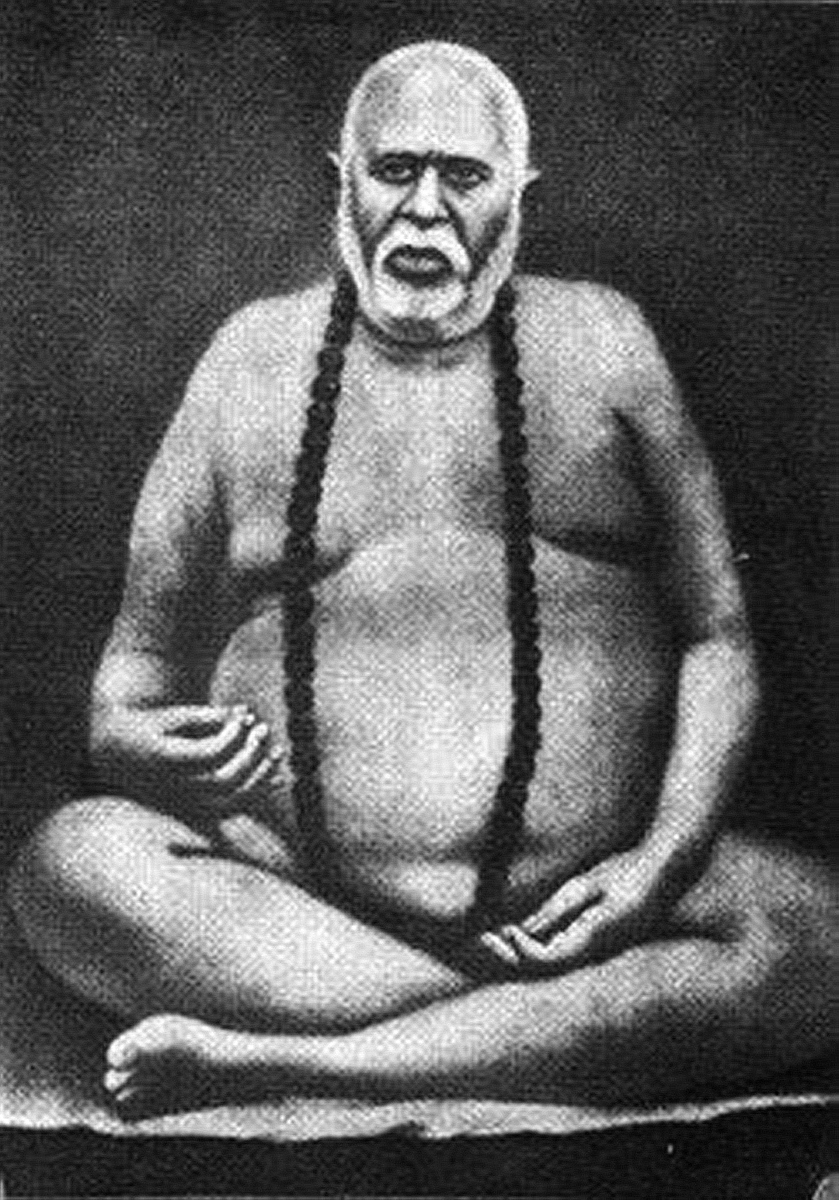

Robert Svoboda’s trilogy mentions other fascinating yogis, one of them being Trailanga Swami. Born on 27 November 1607, he went on to live 280 years, dying on 26 December 1887. Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa called him ‘the walking Shiva of Varanasi’. He weighed over 135kg, and no one ever saw him eat or wear clothes. The British police once charged Trailanga under a nuisance order and put him in jail. A few minutes later they saw him sitting atop the roof of the police station. When the police climbed onto the rooftop to take him back into custody, he sped away and was next seen sitting on the Ganges; when they dived into the river to catch him, he submerged himself in deep waters. Even after ten days of searching the river, the police could not find his body. Right when everyone thought that he had attained jala samadhi (a yogi’s sacred self-drowning), Trailanga suddenly reappeared, roaming naked on the streets as usual.

As you can see, the Eastern yogis were capable of acting beyond physical laws. Could someone be present in two different places in the same form at the same time? Svoboda writes that while talking to his friends in Mumbai in his physical form, Vimalananda could sit and talk to another set of friends in Europe simultaneously, in the same physical state.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons/Debashish Genaamd

The second book in the Aghora trilogy, Kundalini, addresses the tantric practice of Khanda Manda. It is one of the most challenging yoga forms, in which a yogi cuts off his own limbs and throws them into a roaring fire. After a few hours, these limbs emerge from the fire and rejoin the yogi’s body. It starts with a single limb, then two, and goes on until the head is finally severed. “You will faint at the mere sight of oozing blood,” Vimalananda warns his student.

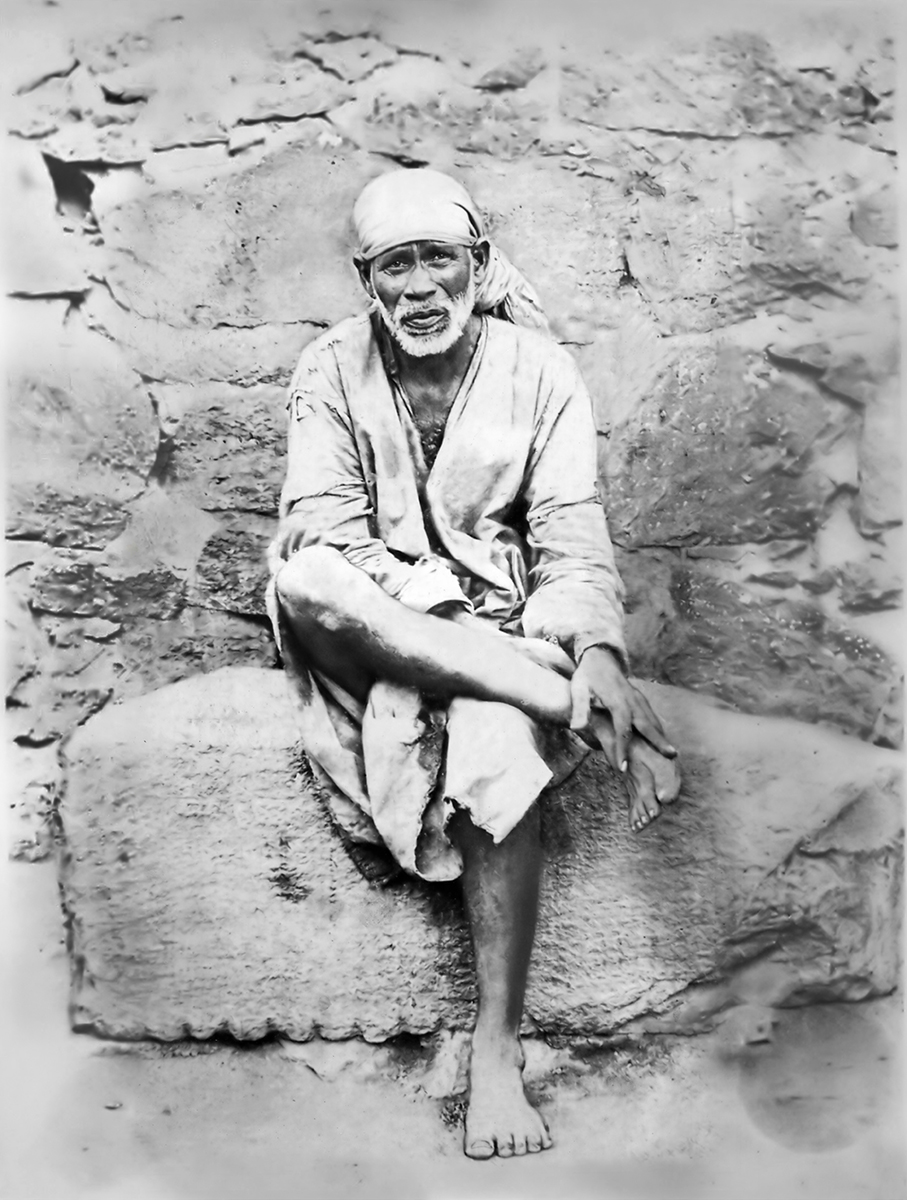

There was a yogi named Sai Baba of Shirdi, in Maharashtra, who is well known among the public now. Devotees who observed him up close during his lifetime (he died in 1918) have written that he had performed Khanda Manda yoga. Some called him a fake during his time. One day a devotee came to see him and was shocked to find Baba’s body cut into pieces. He ran into the village to convey that Baba had been murdered by one of his enemies. When everyone rushed to the site, they found Baba sitting as usual, his right leg over his left.

Another siddhi concerns the power to host a dead person’s spirit in a yogi’s body. Vimalananda is known to have hosted the spirit of Akbar, the third Mughal emperor, several times. When this occurred, his disciples would behave as one would behave in front of an emperor: they would converse in chaste Urdu; they would fill the room with rose perfume and the scent of incense sticks. The trilogy’s third book, The Law of Karma, describes these scenes as though they were from a modern play. There is a part where Akbar jokingly says, ‘During our times, our vehicles (camels, horses) emptied their liquids, but these days, you fill the vehicles with the fluids. It is ridiculous.’ Everyone laughs softly, covering their mouths to avoid laughing out loud in front of the emperor.

Once Svoboda recorded a televised interview, his first ever, during which he mentioned his Ayurveda mentor but said nothing of Vimalananda. At the time Vimalananda was recovering from a severe injury suffered in an accident, and Svoboda had not wanted anyone to disturb him as a result of this interview.

Later, the two watched the telecast together. When Vimalananda realised that his student had not mentioned his name, he became angry and began yelling, saying that the interview must not continue airing. Right at that moment, there was a power cut. The headlines the next day were all about the total blackout across the city of Mumbai, including all television and radio stations. Svoboda called the producer and said, ‘This is the work of my guru. Please rerecord the entire interview or he might burn down your studio.’ Hearing this, Vimalananda laughed. The producer rerecorded the interview, and this time Svoboda made sure he mentioned Vimalananda’s name.

When asked recently if he liked India, a land with innumerable yogis, Svoboda said that he admired the country except for two reasons: the heat and losing his suitcase during train rides. The fact that a woman cannot walk without fear of sexual assault was apparently by-the-by.

Translated from the Tamil by Vidhya Subash