The artist places us inside the body and asks us to have a good, mucky feel around

A woman flops down on a couch, picks up a chicken nugget from the heaped plate in front of her, dips it into a jar of dark-brown sauce and chows down. Then she does it again. And again. After following her last session of fried chicken and breaded chops with more nuggets, her stomach voices its protestations as a croaking grumble. Well, at least it sounds like a grumble, in the video element of Dafna Maimon’s installation Indigestibles (2021), shown at last year’s Helsinki Biennial. But that’s when we start the journey down the other part of the installation, the long, oversize and dimly lit velvety tube next to it: an extended plush red walk-in gastrointestinal tract, complete with its own outspoken chorus of intermittent moans and extended, breathy sighs. It seems natural to wonder whose voices these might be. Perhaps they belong to the woman’s intestinal villi – the small appendages that line our gut, absorbing nutrients? Or to some among the billions of microbes that live nestled along the intestinal tract. Every once in a while there’s a squeal, perhaps a bit of pork being broken down. At points the voices bubble up, shouting and competing, in what seems like a translation of the woman’s unsettled stomach sounds: “Us! Hear us? Us hear us? Can us stop us?”; and then, like bickering children: “Stop it! You stop it!” None of this commotion seems to affect the woman in the video, however. She just keeps eating: more chops, meatballs, nuggets, and mound after mound of fried chicken.

In her monograph Gut Feminism (2015), gender studies researcher Elizabeth A. Wilson notes how the insights of biology have been summarily dismissed in recent decades in order to strengthen cultural and political arguments about how things like gender are shaped; she lists the ‘debris that our antibiological politics have generated: archaic action, animism, rudimentary mentation’. In other words, ignoring biology and its messy materiality is making us stupid and supersti- tious. To counteract this, she proposes a ‘critical splanchnology’ (the study of viscera as a way consciously to re-recognise that there is no separation of body and mind. Dafna Maimon could be seen as the wayward choreographer of such a splanchnology. The Berlin-based Finnish-Israeli artist’s performances, sculptures, installations, videos and drawings set out a comedic but grim portrait of where we’ve arrived as a species, as the planet’s self-appointed apex omnivores. Maimon’s recent works can be seen as a trilogy of sorts on the process of ingestion: from diseased cooking, in her performance Wary Mary (2019), to chewing and mastication in her video and installation Leaky Teeth (2021) and the noisy journey into the intestines of Indigestibles.

Each of us humans has two brains: our much-vaunted bobble-head top brain, and what people like food scientist Herbert Watzke refer to as our ‘gut brain’. The gut brain is relatively sophisticated, comprising around 500 million neurons, which is roughly equivalent to the number you might find in the brain of a cat. Consequently, the enteric (intestinal) nervous system, as the ‘gut brain’ is more formally named, is highly sensitive, capable of sorting through the millions of molecules we put in our bodies and communicating constantly to negotiate the intricacies of digestion (and, on a more fundamental level, when to go looking for food and when it would be better just to stop). In evolutionary terms, the gut brain preceded that of the one upstairs – which perhaps enables us to understand the history of human evolution as a series of ingestions: consecutive consumptions that led to symbiosis rather than just, well, death.

There’s been a complicated, half-digested shift in how pop-tech society has come to perceive this second brain – generally with a sort of distanced, morbid fascination, as if it were an eccentric houseguest rather than an integral part of each of us. Medicine’s demands, particularly around issues of hygiene, are becoming ever more determinant of modern living, and yet we still ignore the body as a thinking, feeling aspect of being. The modern, medicated body is a distanced machine, there to be sedated, fuelled, fed ant-acids, not integrated or listened to – that studious nonattention has created a particular kind of impasse. That impasse is where Maimon works: her human protagonists are solitary women trapped in a limbo of contemporary conveniences. The prim businesswoman in Maimon’s video Leaky Teeth, shown as part of an installation at the Institut Finlandais in Paris last July, arrives at a modernist house in the middle of nowhere, waiting for a plumber to come fix a water leak. She waits for days, dawdling around the house, working on spreadsheets and entertaining herself by watching a reality-TVv show titled Nest Assured: Birds on Demand while nursing a severe toothache and, consequently, pureeing her food before eating it. Shelly, the incessant consumer of Indigestibles, also dawdles, pottering around a small flat as she tries and fails to write something for her blog, intermittently watching a TV show called Last Resort: Dogs on Demand and eating plate after plate of processed meats. Occasionally her phone rings, and each time, the video cuts to another woman on the other end of the line, listlessly chewing a bit of chicken. In Maimon’s projected version of the present, humans are stuck and bored. The other living animals we see are in even worse shape, ogled on the TV as distant entertainment, or simply extinct. Shelly’s one plant pot is lined with dead moths and bees, while the TV constantly blares news updates about the death of the world’s last orangutan and last surviving great ape: “We are now alone walking upright in this world”, the newscaster declares.

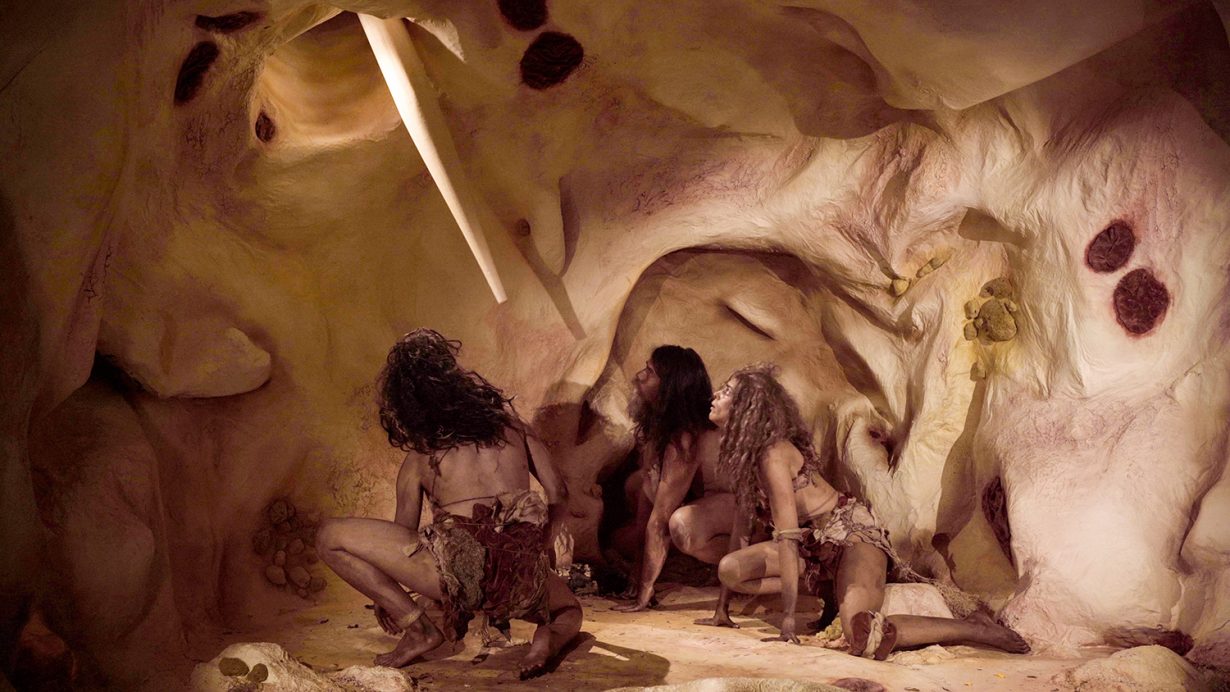

A loopy, wobbly disruption to this monotonous existence comes from the denizens of the gut brain: yelping villi, bouncing bacteria and sensuously dancing microbes. In Wary Mary, a performance Maimon staged in an anatomical theatre in Berlin, a narrator recounts the story of Mary Mallon, a cook in early-twentieth-century New York who unwittingly spread typhoid fever, leading to her becoming known as Typhoid Mary, ‘the most dangerous woman in America’. Maimon’s performance is sympathetic both to Mallon’s status as a working-class scapegoat and to the typhoid bacteria themselves. Three dancers, dressed in velvety pink, with huge pillow-stuffed soft bellies, twirl, bop and push around the theatre to a wonky, slowed-down rumba tune. They look like swollen buboes, or maybe they’re emboldened embodiments of typhoid’s salmonella bacteria. At times they come together in slow, balletic arrangements, and at others they loll ridiculously around the theatre’s floor on their bulbous abdomens, before being rolled up in an oversize cloth tongue. In the video of Leaky Teeth, a set of primeval cave-beings – grunting, grimy early humans who writhe around smelling each other and licking the moist walls of the tooth that surrounds them – live in the protagonist’s wisdom tooth. The woman’s tooth decay gives them a portal through which to access her body; at the end she collapses on the floor, only to be corporeally replaced by one of the tooth-dwellers. The primal being revels in the house’s textures, rubbing her face on the woman’s laptop keyboard, stroking a slipper, cradling a wicker chair, until a door creaks open from a gust of wind and she finds her way outside, escaping into the open air.

The installation of Leaky Teeth included several drawings, densely textured swirls of ochres, browns and dark reds, from which a tooth, a hand or something resembling an intestine emerges. Sections of the tooth-cave seen in the video were arranged on the gallery’s walls and floors, looking more like enlarged, crinkled bits of skin pocked with bruises and patchy growths. As with the giant intestine-portal of Indigestibles, Maimon places us inside the body and asks us to have a good, mucky feel around. Heartburn (an instructional do it at home video) (2021) was released online in conjunction with the Helsinki presentation of Indigestibles. We see the inside of the cloth intestine, occupied by a woman who seems dressed as an indeterminate body part, as a narrator leads us through a relaxation and awareness session: “Welcome to deep inside you. You’re going to be spending some time here.” The video encourages you to feel your breathing, then to explore the space around you using first your mouth, and later your “primitive gut tube”. Here, as the flesh-woman rolls around the floor of the intestine, we are left simply with the encouragement, “Explore. Enjoy.”

In recent years, researchers like Watzke have suggested that ‘omnivore’ isn’t precise enough to describe the peculiar evolution of the human digestive system, proposing instead ‘coctivore’, from the Latin coquere, to cook, as better reflecting how our cooking of food allowed us wider access to nutrients, leading to smaller stomachs and greater mobility. Maimon’s work plays out where the coctivore’s stomach is leading: to a sauce-loading and lip-smacking lonely little corner where everything is overcooked and overconsumed. The shameless sharing of salmonella, the cavorting slap of bouncing viscera, the moaning mingling of bacteria – these, Maimon suggests, are a way to feel our way back into the contradictory multiplicities of the body. It’s not so much a case of ‘you are what you eat’ in Maimon’s world, but ‘you are how you eat’, how you chew and swallow, and who you are eating with – the slow communal dance of ingesting the world, waving gently as I dissolves into us.