The new show at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York revives a time in which collaborative cultural production thrived not only from consensus but also from debate

Two figures in fur coats pose for James Van Der Zee with their gleaming Cadillac V-16 parked in front of brownstones in Couple, Harlem (1932), an intimate and nostalgic gelatin silver print. A studio portrait from the same oeuvre, Person in Fur-Trimmed Ensemble (1926), captures the glamorous countenance of an individual likely dressed for a drag ball at the Hamilton Lodge. Van Der Zee, whose work is a mainstay in The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, documented a period of cultural revival that blossomed in Upper Manhattan and internationally during the 1920s. His photographs were by nature collaborations between himself and the Black cosmopolitan urbanites he encountered on the streets or hosted in his studio. Running through the 160-work survey of Van Der Zee’s milieu is, likewise, a palpable sense of the collectivity that sparked what is now called the Harlem Renaissance.

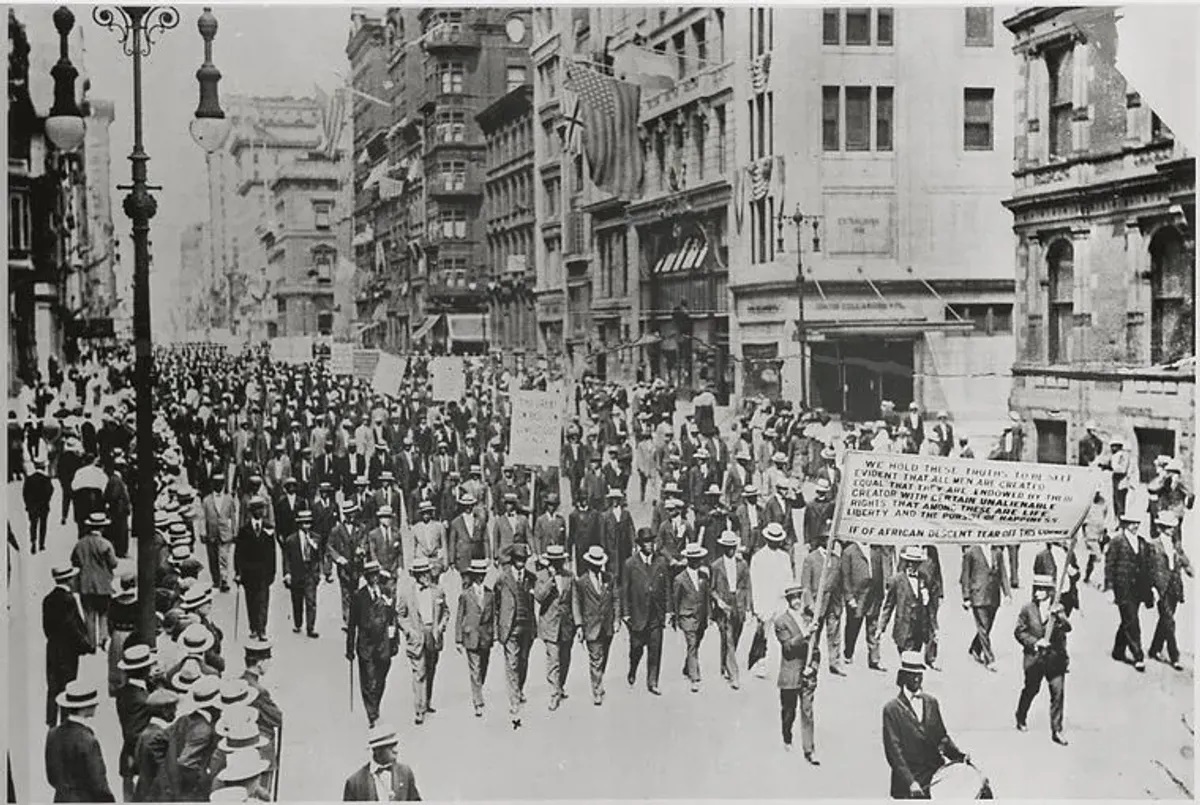

From the start of the Great Migration (1910–70), when six million Black Americans fled the Jim Crow South for the Northeast and other parts of the US, to the Wall Street Crash of 1929, approximately 175,000 African Americans lived and prospered in Harlem, an eight-square-kilometre neighbourhood north of Central Park, where they threw interracial soirées and published periodicals highlighting Black intellectuals, some of which, including The Crisis (1910–) and Opportunity (1923–1949), appear in vitrines among the show’s ample selection of printed matter.

In Harlem, collaborative cultural production thrived not only from consensus but also from debate. According to the exhibition materials, Black literati of the 1920s were split between two divergent strategies for racial equality. The first, proposed by W.E.B. Du Bois, who founded The Crisis, deployed Black art as a rhetorical weapon against existing racist propaganda. The second, spearheaded by Alain Locke, who wrote for Opportunity, urged for art to be treated as autonomous self-expression rather than as rhetoric. The shortlived but radical magazine Fire!! (1926) charted a third course. Founded by a cohort of writers and artists who sought to address heterogeneity within the Black community, Fire!! featured writings on colourism, prostitution and queerness. Its first and only issue appears here with the scowling Sphinx on its red-and-black, Aaron Douglas-designed cover facing, as if to challenge, the demure, leashed lion on the cover of the more conservative Crisis’s September 1924 issue, illustrated by Laura Wheeler Waring.

Throughout the exhibition, paintings, sculptures, photographs and films are grouped in ways that underscore competing visual idioms, such as those of Archibald Motley’s Portrait of a Cultured Lady (1948), an oil painting that depicts the gallerist Edna Powell Gayle in an elegant interior and a naturalistic style, and William H. Johnson’s Woman in Blue (c. 1943), one that monumentalises an unnamed Black sitter in a folk art-inspired idiom, with bold outlines, exaggerated proportions and thick impasto. One of the subtler arguments the layout evinces is the inversion of traditional hierarchies of centre and margin. Works by white modernists such as Henri Matisse and Roland Penrose supplement, rather than overshadow, those of Black luminaries and are limited to those depicting convivial interracial relationships: actress Aïcha Goblet sits smiling with the Italian model Lorette in Matisse’s painting Aïcha and Lorette (1917), while model Ady Fidelin dozes with three white contemporaries in Penrose’s C-print Four Women Asleep (1937).

Perhaps because it carries the weight of The Met’s infamous 1969 exhibition ‘Harlem on My Mind’: The Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968, which presented the neighbourhood through the lens of photojournalism and, according to reviews at the time, without sufficient didactics, The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism offers no shortage of conscientiously positioned and meticulously plotted visual arguments. The thoroughness produces, paradoxically, a longing for anomalous and unruly artworks that might prompt viewers to engage actively in interpretation. A spark of potentially unsettled meaning arises in Friends (1942), a lithograph made by Margaret Taylor Goss-Burroughs over a decade after the Wall Street Crash. It shows two women, one of whom appears Black and the other white, seated shoulder to shoulder, facing forward. According to the wall text, their mirrored poses convey how ‘human commonalities transcend racial difference’, but the image implies a more complex camaraderie. The women in fact both sit with their lips pursed and their arms crossed, as if they’ve been arguing. In light of the interpersonal negotiations that were required to produce the cultural renaissance in Harlem, one suspects their friendship was likewise tempestuous and hard-earned.

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, through 28 July