The unspeakable nature of chronic illness is explored by Emily Wells in a new book that examines the limits of language

In A Matter of Appearance: A Memoir of Chronic Illness, Los Angeles-based writer and former dancer Emily Wells describes the literary project of writing about pain as ‘figuring out how to write a perpetual scream.’ This scream is intended to convey the ongoing, open-ended nature of chronic illness, and the translation of it into a finite number of words upon the page is an inauspicious task. Many writers must grapple with the concept that Elaine Scarry asserted in her book The Body in Pain, that pain evades language. How, then, can a perpetual scream become legible?

Non-fiction writers of pain and illness, from Alice Hattrick to Gillian Rose to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, often take a measured or dignified approach to writing about something so abject that it is supposedly unsayable. Experience is intellectualised, stymied out into areas of external interest so that we might be able to associate pain with an outside signifier. It involves looking at representations that may already exist so that their variable truth can be examined. In Wells’ book these interests are ballet, modelling and hysteria; the way bodies move in performance, in appearance, and how they then perform in private, in pain. While often the question of the appearance of illness or pain is placed squarely in how the ill person chooses to represent it, it is equally a matter of how that representation is received.

In Anne Boyer’s 2019 memoir of cancer, The Undying, she imagines a plan to create a crying installation, ‘a place of public weeping’, while speculating that this could invite angry or dismissive responses. Boyer’s stark depiction of a general reluctance to witness pain is suggestive of how chronic pain and illness is an isolating and defensive experience. She reflects upon this image as a metaphor for the problem that arises in exposing one’s suffering, whereby it can operate not only as a comforting mode for sharing that pain but also invite attacks from ‘anti-sadness reactionaries’. It is not difficult to imagine such reactionaries. The western world has historically shied away from overt expressions of emotion, often dismissing them as ‘hysterical’. Symptoms, whether emotional or physical, are sought to be put under personal control.

Wells’s rare autoimmune disease is only diagnosed when she becomes an adult, having suffered since childhood from symptoms that were chalked up to her emotions. Yet she quickly begins to understand that ‘just because something has a name doesn’t mean people believe it is real.’ This follows in medical scenarios: being asked to quantify pain on a scale of 1 to 10 is a struggle, ‘unsure of how to turn a sensation into a number’. A nurse asks her if she is anxious, and she reflects that she was ‘anxious about being anxious without language to express what the body felt.’ Throughout A Matter of Appearance, Wells exposes the tensions between seeking a means of expression while not wanting to make one’s story of pain into a tragic fable. She seeks to communicate and be listened to, while simultaneously coming up against the limits of language. When she uses the phrase ‘attacked by itself’ to describe her body’s autoimmune responses, she reflects that writing the word attacked feels ‘false—or true only insofar as I can find no better alternative.’ Perhaps it is safer to say that the literary project of writing about pain is akin to the risk of rupture, just as the body is.

One of the central questions of Wells’s memoir circles around the value assigned to an understanding of the root cause of pain, a link to a past event that the open-endedness of chronic illness can rarely provide: ‘Why does talking about trauma remain one of the only socially acceptable ways women can discuss health, discomfort, or pain?’ This is an especially germane question alongside discourse surrounding trauma as an over-saturated and perhaps unnecessary literary or fictional trope. In 2021, Parul Sehgal asked whether ‘in a world infatuated with victimhood, has trauma emerged as a passport to status?’ More recently, the stage adaptation of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life has come under fire for its brutal depiction of trauma-based self-harm. Wells is forthcoming about her resistance to ‘re-narrativizing the past’ because ‘one’s own pain is simply not a tasteful object of contemplation’. But, as she argues, ‘when pain is unspeakable, it remains invisible.’

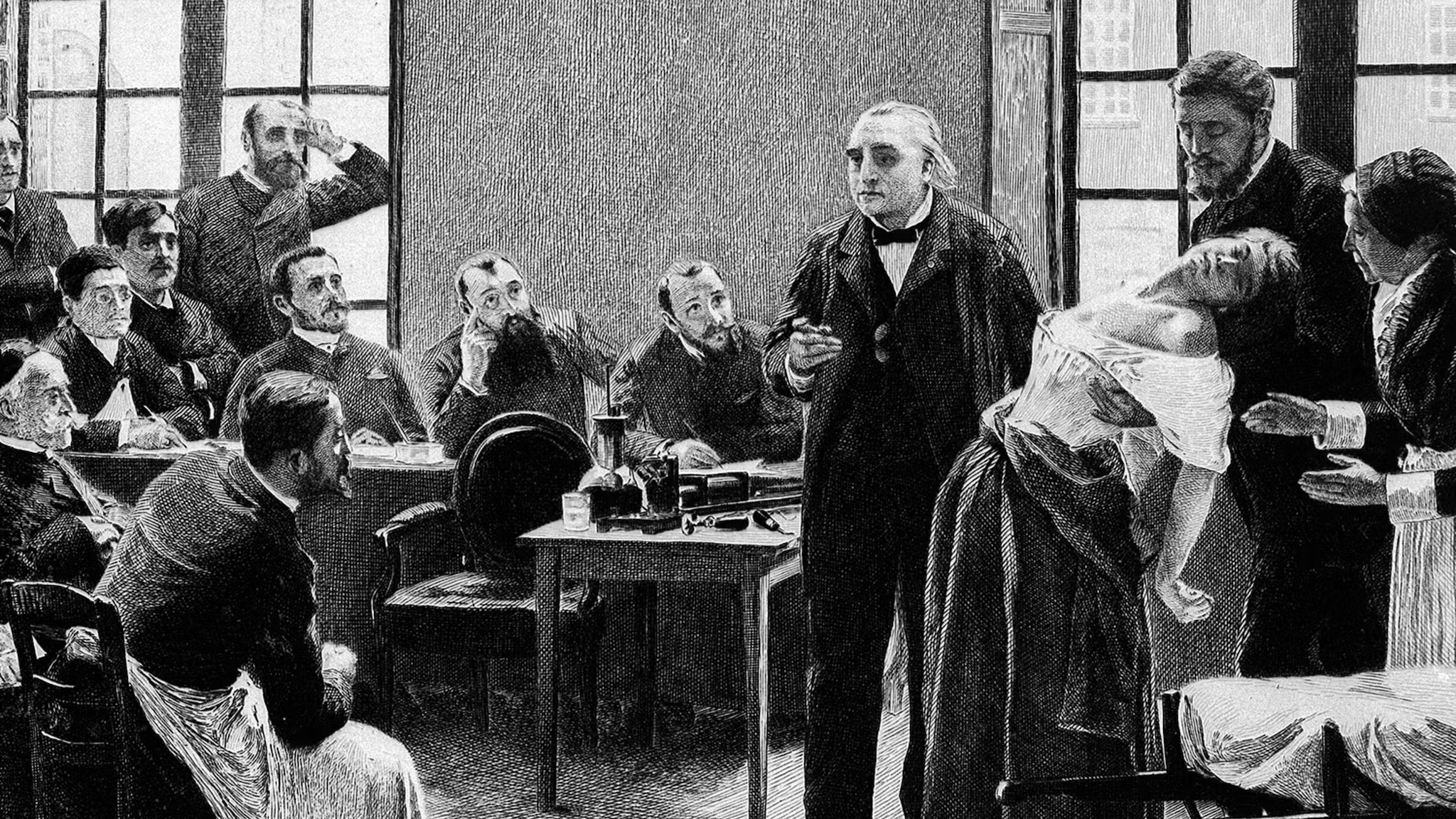

Again the question arises of how to make pain visible. She is drawn to a specific set of images depicting patient Augustine Gleizes, who was admitted to the Salpêtrière women’s hospital in Paris in 1875 at the age of 15, in various states of supposed hysteria: ecstasy, mockery, eroticism. Wells speculates that this could be ‘because they offered some false hope that pain could be made visual.’ She is not the first to reclaim the icon of the hysterical woman – French feminists Hélène Cixous and Luce Irigaray saw hysteria as a form of female resistance – but it is through images of Augustine that she is able to channel her occasional wordlessness: ‘When I can’t get my thoughts down,’ she recounts. ‘I look at the photos.’

These images are a place of recognition, and Wells ties them to photographs of her own modelling days. While Augustine’s hysteria is heightened in photographs almost to the point of allegory, Wells-as-model exposes the thin line between revelation and secrecy for a person in pain. In her modelling photos, Wells is ‘aligned with the aesthetic of the time’, ‘cold, bereft, absent.’ Her appearance is at once a direct result of her illness and something that exists despite it. This distinction between the self that is presented to the world and the self in pain is the slippage that ruptures Wells’ experience of chronic illness. One evening while partying with a very LA crowd, Wells fights collapse on a rooftop by curling into a foetal position, hoping ‘it might be seen as playful’ to lie down. But this disguise is not enough, and the designer with whom she has been sharing lines of cocaine reveals the judgement in her eyes: ‘pity’.

What is often missing in so-called trauma plots or misery porn in literature, television and cinema is an examination of the environment that allows that pain to be ignored, amidst which it goes untreated and is allowed to proliferate or is magnified to such an extreme level that it loses any connection to sociopolitical reality. Augustine’s doctor Charcot is ‘completely uninterested in his patients’ words’, even when they relay their trauma. His hysterical patients are both a spectacle and an experiment, objectified in their pain. As Wells discovers, their images can only exist within the context of the asylum, rather than a universal example of pain made visible. Pain, as she ultimately discovers, is too specific for the generalities of language, and evades us even when we take the first step and begin to speak of it aloud. Writing through and of pain will inevitably include these complications of expression, and A Matter of Appearance serves a reminder that it is still worth trying to translate a perpetual scream.