The Brazilian curator is the first Latin American to helm the Venice Biennale. John-Baptiste Oduor finds out how Pedrosa’s work as director of the Museu de Arte de São Paulo inspired the exhibition in Italy

John-Baptiste Oduor Soon after you took on the position of director at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo in 2014, you put on the show Picture Gallery in Transformation. In it you made the decision to hang the work on glass easels. Part of the justification for this was, you said, that you wanted to desacralise the work and make the space more democratic. Could you say something about what you meant by that and why it is important?

Adriano Pedrosa The glass easels were actually designed, implemented and conceptualised by the architect of the museum, Lina Bo Bardi. Bo Bardi introduced the glass easels in 1968 when our museum, the current building, opened. She then conceptualised and designed that whole gallery with the glass easel system. So it’s not my idea.

The glass easels were at the museum until the early 1990s. Then they, the curators and directors at the time, decided to take them away. And when I started working in the museum a decade ago, my first proposal was to bring back the glass easel display system, which I did back in 2015. My decision to do so was a return to the approach of Bo Bardi.

She was quite interested in these two things that you’ve mentioned, desacralising art and offering a more democratic approach to it. The idea basically is that when you enter the gallery you can walk through the artworks and the whole gallery resembles a forest of artworks. The artwork becomes an object almost. And there is almost this Brechtian effect when you look at an old, very old, painting from the nineteenth, eighteenth or seventeenth century, and can look at the back of the work, that side of the work that’s not supposed to be on display. It’s almost like looking at the back of a theatre.

JBO It makes me think of Clement Greenberg’s idea that premodern art conceives of a painting as being a cavity in a wall, inside of which a small scene is playing out.

AP That whole thing is gone. The idea of the window, for example, is completely gone. There’s another element that’s quite interesting in the glass easel display at MASP. The whole museum comes from a certain Bo Bardi design. She’s referencing brutalism, so there’s a lot of concrete. And the floor is black rubber. In the space you can see a lot of the metal elements of the architectural construction. So there is a certain rawness to the architecture and its materials, which contrasts with the collection at MASP. There we have works from sixteenth-, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century artists and artists from the 1920s. This is a very rich European collection.

There is quite a lot of contrast between the sort of fine arts tradition of European art and the rawness of the architecture. I have chosen the same exhibition design and display in parts of the show I am curating at the Biennale. There I will use the glass easel display in one particular section of the exhibition called ‘Italians Everywhere’, which will be on display in the Corderie of the Arsenale, which has its own rawness. It’s of course not concrete and rubber, the modernist kind of brutalist rawness, it’s another type of rawness of exposed brick, of the very old construction of the Arsenale.

JBO Many people have observed that your curation shows a preference for artists from the Global South. What do you see as distinctive about the narrative around modernism that you’re providing, one that isn’t centred on Europe or artists living within a ten-mile radius of central New York between the 1930s and 1960s?

AP My curatorial decisions are to do with where I’m coming from. I am not the first curator from the Global South. I am the second curator from the Global South, after the wonderful, great late Okwui Enwezor, who curated the Biennale in 2015. But I’m coming almost ten years later. I am indeed the first curator living and working in the Global South. Okwui was, of course, working in Munich at the time.

The landscape is very different to the 1980s when Documenta was mostly European – almost exclusively European. So the past couple of decades, we’ve seen that these exhibitions [such as Venice] have opened up to the contemporary scene, to contemporary artists, but it’s been more difficult for the artists that are from the twentieth century. So that’s why I felt it was important in this exhibition to look at these artists from what you’re calling the modern period.

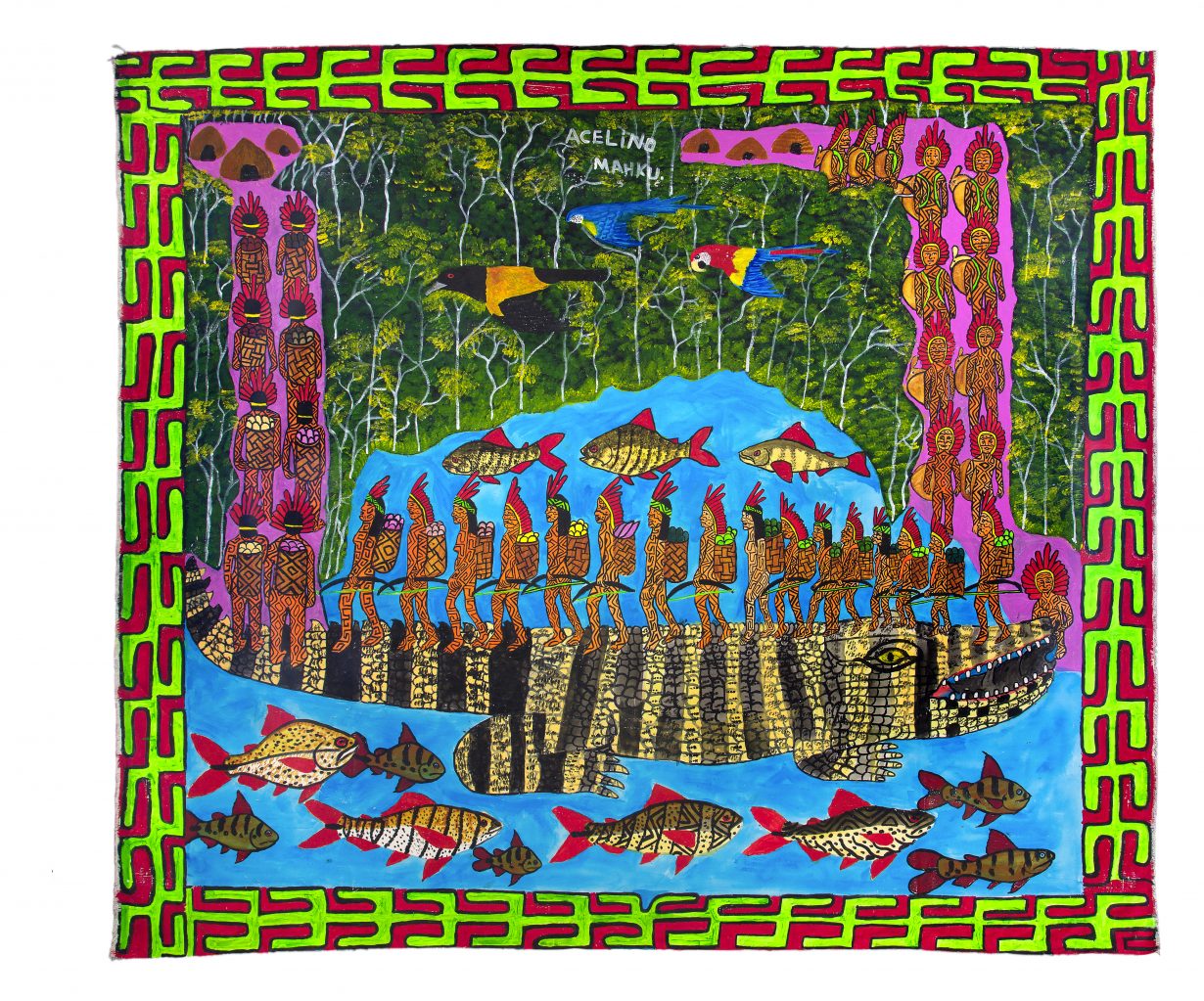

There is something else that I should add. The title of the exhibition is Foreigners Everywhere. We have divided this theme into four different subjects, which is the Foreigner, the Queer, the Indigenous and the Outsider. The idea in the Nucleo Storico [section of the exhibition] is that modernism itself travelled throughout the twentieth century. Modernism travelled to Africa, to the Middle East, to Latin America, to South and Southeast Asia. And many artists travelled through modernism or, you know, went to Paris, lived in London, lived in Rome, lived in Berlin, lived in New York, lived in Amsterdam, Madrid, Portugal.

JBO There are these incredible stories of Rubem Valentim, one of the Brazilian artists you’ve selected, at the British Museum copying out Yoruba sculptures by hand and then fusing them with his ideas of Afro-Brazilian culture.

I also wanted to ask you about the ongoing Histórias series of exhibitions that you have curated at MASP on Brazilian history and culture. In it your approach to curation seems to me to be quite monumental. That is, curation in the mode of a reinterpretation of fundamental concepts and ideas that we use to understand the world. Is this correct?

AP In terms of the Histórias series, which has been going on since 2016, we have always been interested in certain themes and notions and concepts that are not necessarily art historical. So at this stage, we wouldn’t do histories of abstraction or histories of expressionism or histories of colour. We are really interested in notions more focused on social histories of art, if you like, and certain themes that speak to, you know, everybody, regardless of their interest in art.

Although the Histórias series has these all-encompassing titles, like ‘Histories of sexuality’, it contains the idea of plurality, diversity and also of fragmentation and incompleteness. They’re not definitive histories, in Portuguese histórias has a broader meaning than simply history. They’re not master narratives.

But histories of art in the twentieth century, in Latin America, in Africa, in South and Southeast Asia are not well known internationally. Many of the artists I have chosen for the Biennale are in fact canonical figures in their own country. If you look at the Brazilians, for example, they’re so well known in Brazil. The same is true of the South Africans; I have a lot of South African artists. I have a lot of Egyptian artists, a lot of Nigerian artists, a lot of Indian artists. These names would be very well known for the art audiences in those respective countries.

You know, we have Frida Kahlo in the exhibition who is of course a very well known name, but it’s the first time she has participated in the Biennale.

JBO Which is incredible.

AP It’s incredible.

JBO You talked about the kind of curation you’ve been doing at MASP and at the Biennale in terms of social themes. Rather than having a show on modernism, a show on figuration, painting or drawing you’ve taken a more social perspective, thinking about questions of sexuality or Indigenous culture. How do you overcome the worry that you’re somehow avoiding or subordinating more formal artistic concerns in taking this approach?

AP With Histórias, the focus has been on multiple narratives. And there are many layers of narratives, right? There are narratives focused on formal issues, taken up by more traditional art historical approaches. These narratives are just some of many, many possible narratives. When we talk about the work of the artists selected, we’re not ignoring that discourse. That is still there somehow. But it’s just one of the many possible layers, one of the many stories.

There are many narratives, many histórias. One of them is that particular narrative [focused on formal issues]. We’re not taking that particular narrative as the main narrative of the frameworks that we are developing, but we’re not ignoring it altogether.

John-Baptiste Oduor is an Associate Editor at Jacobin.

The 60th Venice Biennale, 20 April – 24 November