“I’m thinking about an institution as some kind of archaeological truth”

Having first come to international prominence following his contribution to the 2015 Venice Biennale (curated by the late Okwui Enwezor), a largescale installation of jute sacking titled Out of Bounds (2014–15), Ibrahim Mahama has established himself, over the course of the following decade, as one of Ghana’s leading contemporary artists, with a series of works that explore the operations of collective memory, and the impacts and legacies of trade, migration, commerce and colonialism in Africa. Much of the work features a signature use of everyday materials (notably jute sacking) that evinces the presence of people and their labour within these networks, but is often considered redundant in the broader narratives implicated by his work.

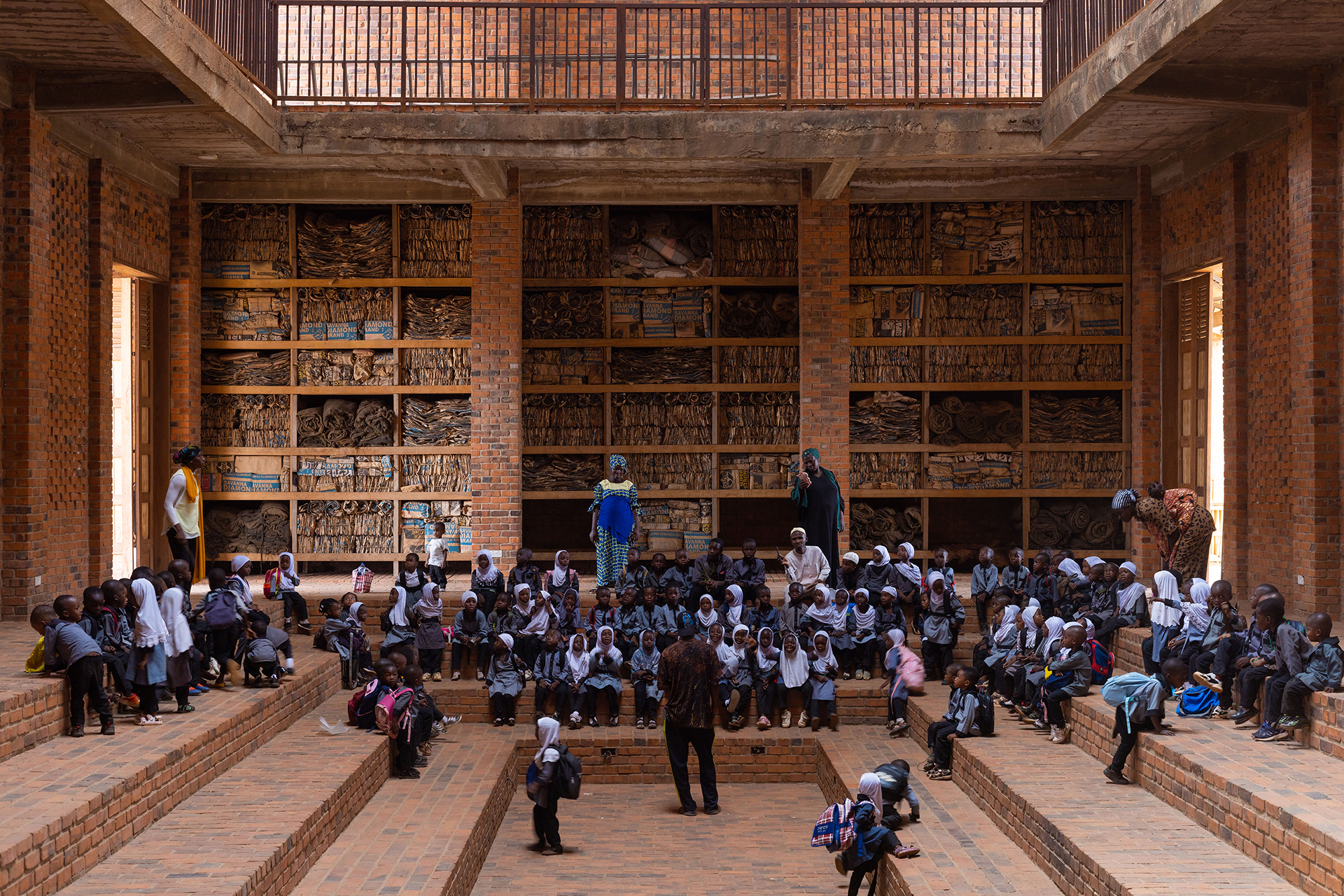

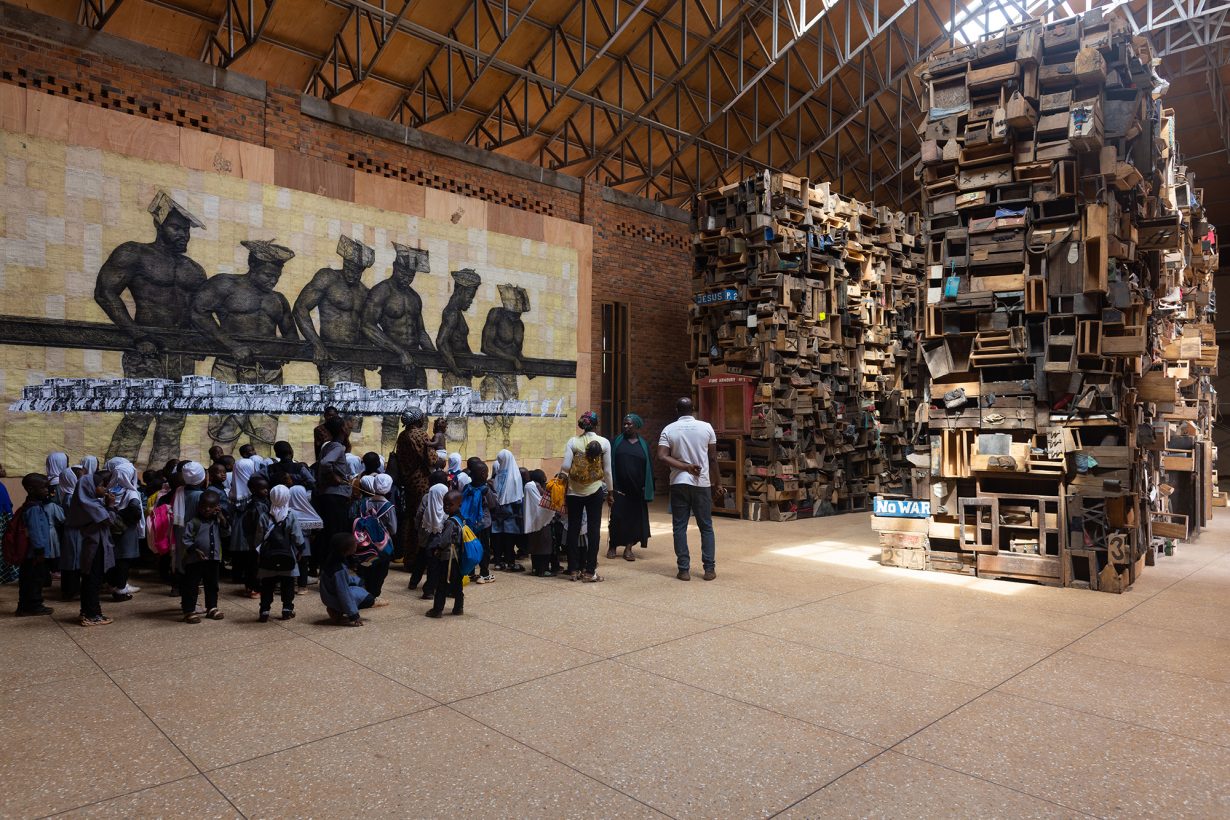

In parallel to this, and as his artworks have led to commercial success, Mahama has engaged in a process of ‘redistribution’ of the income his art generates, founding the Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA), Red Clay Studio and Nkrumah Volini in his home city of Tamale. ArtReview caught up with the artist, via Zoom, to talk about the many facets of his practice, as he opened his latest exhibition in London, at Sessions Art Club in Clerkenwell. And before he was ranked number one on ArtReview’s Power 100.

ArtReview Your work often draws on industrial materials and labour-intensive contexts and processes. How do you think that showing such materials resonates with different locales, say with your two current exhibitions in the context of London?

Ibrahim Mahama It’s interesting because, for instance, in the Ibraaz space, the building began to be used as an arts centre in the early twentieth century, around the same time when the British were building the Coastal Railway. Ghana at that point was already a leading producer of cocoa in the world, and a lot of the cocoa that was being produced in Ghana was extracted by the British. It would have been taken to London and other European centres at the time.

Of course, while today the Ibraaz space has been transformed into a cultural institution that allows for a certain kind of critical reflection on history, I thought that by bringing the residues of these facts – using wood from the railway and then chairs which were also produced by the British around that same time – into the context of Ibraaz it would somehow spark new conversations, particularly within the era that we find ourselves.

While Ibraaz is more like an installation which invites you to use and to sit on it, in the Sessions Arts Club the work acts more as a visual thing, like a painting to be looked at, and to interpret in your own forms. There’s work made with canvases that are used for transporting goods around the country, which have engine oil soaked in them. Then we have these photographs that depict the arms of the women who mostly travel between the northern part of Ghana and the south to do odd jobs. They include transporters and exporters in transport goods from the market to people’s homes. I’ve been thinking about the history of weight and the burden of it, looking at it in relation to colonial maps and other surfaces.

I’m interested in the residual quality of the elements within the work. A lot of people in the West, particularly if you’re in London and you’re consuming goods and commodities that are coming from other parts of the world, you really don’t reflect upon the labour that goes into producing those things. I thought that it’s quite interesting to be able to have that residue just hanging on the wall, which is there each time you look at it, the smell, the textural quality, even the oil when you touch it stains your hands.

AR Sessions House is just across from the Karl Marx Library, where London’s May Day parade starts from.

IM Marx has always been very important to me, especially when I was studying. When I was at KNUSTUniversity studying painting, one of our professors, Kąrî’kạchä Seid’ou, was very much interested in this question of how we can transform art from a state of commodity into a gift.

A lot of historical paintings were of subjects who were being exploited and who were under extractive systems: Black subjects, poor subjects and other minorities being depicted. Although the programme at the university was mostly focused on skill, that focus really didn’t give you the time to think about what was happening within the world of the painting itself, the conditions. For us, it was very important to somehow start from the point of the condition. You cannot think about a condition without thinking about people like Marx. Also, clearly about ways in which we can redistribute the sensibilities that come along with artmaking.

AR You’ve argued recently that it is part of the responsibility of an artist to act as a point of redistribution.

IM For us, redistribution is very important. If I think about even Ghana’s history from the mid-twentieth century, Kwame Nkrumah, who was our first president, was a young chemist who had a dream of uniting Africa and transforming the economy, lobbying to industrialise Ghana. He built the first major hydroelectric dam, and built a very important company called the Food Distribution Corporation. At the time, because Ghana was one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement, the idea was that we would learn from countries like Cuba, where food was a commonplace – you could go to a food bank and get food.

We started building these commercial spaces where we could store the commodities that, under the colonial period, were constantly being exploited. In 1966, when he was in Vietnam to mediate peace, Nkrumah was overthrown by a military coup. A lot of these projects he started were completely abandoned. They later renamed the Food Distribution Corporation the Former Food Distribution Corporation. You can imagine if they say something is ‘former’, then it’s no longer doing its work, but it almost means it never really even did its work.

I thought that, philosophically, there was a lot to learn from that period in history. Food is not just about what goes into the mouth. It’s also about thoughts, it’s about reflections, about ideas, how we consume history, how sensitive we become to it, and the subjects that are within that history. Redistribution is very important. How do we redistribute our common histories, all the things that come along with cultural sensitivities?

AR Talking about redistribution, there’s a sense that shows such as the ones we’re talking about, or Purple Hibiscus, your intervention in the Barbican last year, make people in London feel better about themselves or about any guilty feelings they might have, without actually having to do any redistribution themselves. That’s one of the problems of art, perhaps.

IM I think art poses a lot of contradictions. For me, I always try to find the balance within the critical discourse of the work in terms of its production, but also in terms of where the work is emerging from – how the work becomes part of the cultural landscape within that space. In the case of Ghana, there’s the work we’re doing in Tamale, with Red Clay, SCCA, then Nkrumah Volini and many others, also with the blaxTARLINES collective that I’m part of.

When I was making the work for the Barbican, it was very important that the work was produced in Ghana with people from the local community, and it was produced in such a way that it also reflected upon the architectural history of the building of the Barbican, even the texture of the building and how all the concrete was chipped by hand to give it that rough finish. Also thinking about it in relation to the events of the Second World War.

I realised that when we did a project in London, I shouldn’t say a lot. Some people at the Barbican were not very happy with it; some people really protested and said, “Oh, but why should we have these rags and things from Africa hanging on our building?” But it allows you to be able to reflect. Not everyone in society wants to reflect, but it’s important sometimes for them to see these things, whether they like it or not. We know the history of the empire and all that. But people always like to distance themselves, as if no one had anything to do with that. But it’s very important; the only reason we make art is to remind us of why we should reorganise the world differently from how it is.

AR Do you think art can do more than that and play an active part in the redistribution? In some ways, art exhibitions seem like small things compared to what a government can do.

IM When I started making art, the point was about also how to use the contradictions embedded within the artworld. For instance, capital that is generated out of artmaking. Then, using that capital as a means to be able to build, let’s say, new cultural institutions, whether educational institutions or facilities or whatever, to be able to allow for people to have a different quality of life.

For instance, in Tamale, where I was born, up until the last five to ten years, there was never any relationship with contemporary art within the city. I thought that it was very important, because it’s not just good enough for an artist to make a work of art or an installation. I’ve also realised that over the years, as with a lot of artists from the Global South, most of the work that has been made has always been acquired by Western institutions. Of course, a lot of artists will find themselves in the West.

It seems quite normal because if you’re a British artist working in London, like Tracey Emin or Antony Gormley, you know that the National Arts Council or the Tate is going to collect your work. They’re going to keep it safe because they need to preserve it for posterity. Of course, they might also go along and collect works like mine, or Amoako Boafo or many other African artists, or Asian or South American artists. But the question is always to what extent, because at the end of the day most of these artists were coming from other parts of the world. When it comes to the question of redistribution and how people, especially young people and children, understand their relationship to the kinds of artwork these artists make, and the critical discourse that is within it, it is sometimes almost zero to none. We cannot talk about justice when the question of justice is still somehow tied to a certain kind of colonial history, particularly when it comes to the question of capital.

AR Would that also mean rethinking what a ‘museum’ is? In some places where there might not be formal state-run institutions, perhaps there don’t need to be – because there’s not necessarily an insistence on permanence. It’s also interesting in the context of your work, as many of the installations evade a sense of permanence.

IM For me, one of the things that we just wanted to think about was the idea of the institution itself, like the form that it takes. I think where I am at the moment, for instance, institutions take a different form because some things don’t have to be permanent. Whether some parts are permanent, some parts of it are temporary, but the most important thing about the institutional building is: can it allow us to be able to go into history and excavate memories?

I’m thinking about an institution as some kind of an archaeological truth. How do we use an institution’s building as a way to allow younger populations to be able to think differently about time and their place within that time and their place within the world, whether it comes within the permanent or nonpermanent form?

AR There’s a sense in which history is always contingent. That history is this extremely unstable thing that gets written and rewritten, or completely made up. You feel that in many countries, like Singapore, where I am now, which have colonial histories and were only recently formulated as independent states.

IM I think about the history of Ghana in terms of the trajectory that we’re in, and in relation to Malaysia and Singapore. I have a show I’m doing in Singapore in January – Ghana has quite an interesting history with Singapore, because during the founding of Singapore, Ghana used to send engineers to help them industrialise. Some engineers and other people from that part of the world also came to Ghana.

AR Is that something that you think about with Ghana, how it entangles with different geographies?

IM We’ve had many entanglements with different geographies, even as far back as, let’s say, the last 200 to 300 years, aside from the transatlantic slave trade. Certain plants and species that were brought to Ghana during the colonial period, like from Asia, like rubber and other things in the postindependence era. Engineers were sent to the Soviet Union, Malaysia, Singapore, India, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Poland, doctors trained in Cuba, in Russia. There’s been quite a lot. Doing an exhibition and doing research for it – you find out some of these things, or learn of certain individuals who existed within certain timelines, and that whatever work they did also somehow contributed towards certain acts of freedom, it becomes quite interesting.

AR What if someone comes to your work and has a purely aesthetic response, and just loves the textures or the materials? Is it disappointing that they don’t take it further?

IM When I start making my work, I don’t start from thinking about all these histories. When I’m walking around in a market space in Ghana, and when I see these materials, the first thing that comes to mind is the texture and the basic form of these objects. When you stay with the materials, you learn from these over the years, you learn their history, how they were introduced to the place you’re working in and where they come from. Tomorrow I’m travelling to Kochi, because I’m showing at the Kochi Biennale. All these materials that I’ve been working with for all these years, they come from India and Bangladesh. This the first time I’m going to India, and the first time I’m going to work with the material in that context.

Work by Ibrahim Mahama is on view at Sessions Arts Club, London, through early 2026 and in his solo exhibition Parliament of Ghosts, at Ibraaz, London, through 15 February. Mahama’s work is also included in the 6th edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Kochi, 12 December – 31 March

Explore the 2025 Power 100 list in full