“I believe that objects can distil and be vessels for the frequency of the maker. I believe that artistic practice is also spiritual practice”

After discussing the possibility of an interview for five years, Jordan Wolfson and I eventually found our way to talking last summer. I visited him at his temporary studio, an inconspicuous, drab warehouse in an industrial corner of Los Angeles that Wolfson had acquired solely for the sake of realising Body Sculpture, his newest largescale work. The main room held the sculpture and some provisional furniture, but the building’s many office spaces were empty and darkened, giving the studio an unsettling, haunted atmosphere.

This meeting was intended to be the official interview, but Wolfson had to postpone. He told me he was overwhelmed with the project’s final stages before shipping it all to the National Gallery of Australia, in Canberra, which had commissioned the work from him five years before, around the time when this interview was first discussed. This is the longest Wolfson has ever worked on a single piece (partly due to the pandemic), and during this period he created other, smaller projects. One such work, ARTISTS FRIENDS RACISTS (2020), is a wall of holographic fans whirring through a grid of illuminated digital iconography, with the aesthetic of clip art and emojis. This piece, he told me, allowed him to work more intuitively and less pragmatically. “I want a full life of artmaking,” he said.

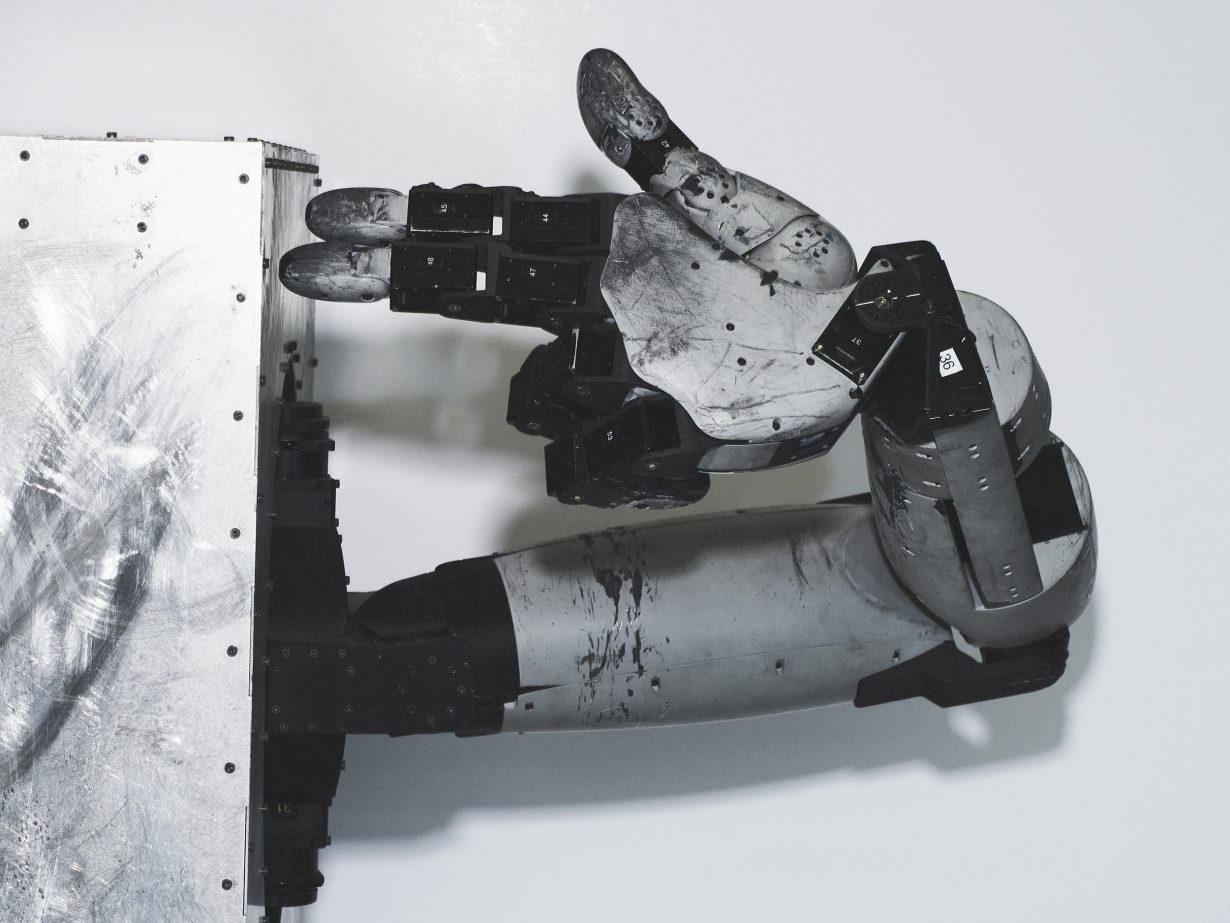

So on that afternoon, instead of an interview, I observed as four technicians worked with Wolfson to adjust the movements on Body Sculpture. The work appears practical and industrial, like something from a factory: a metallic, cube-shaped robot dangles over a stage by a chain, accompanied by a robotic arm. But the piece grows complicated as the cube comes to life, miming through its 30-minute choreography, slowly and purposefully, as if its artificial mind were studying human body language. At different points the robot embraced itself, beckoned to the audience and violently beat a chain against the stage.

Body Sculpture is a clear continuation of Wolfson’s two previous animatronic works, (Female figure) (2014) and Colored sculpture (2016), which brought him to worldwide attention, both for their technological ambition and controversial spectacle. The former depicted a witch, erotically dancing; the latter an oversize male doll being subjected to torture – and both kept their angry, uncanny gazes fixed upon the viewer.

Like those works, Body Sculpture enacts an eerie animatronic performance for the audience, but unlike them this work is mostly silent, without musical accompaniment, and despite its name does not resemble a body. For all these reasons, my experience of Body Sculpture was more abstract: free of the disturbing faces and sociocultural connotations that have defined Wolfson’s earlier works. On that day, I walked away from the studio with a lingering feeling of mystery.

About six weeks later, Wolfson and I finally sat down to speak, his dog Broomstick at our feet. By then the warehouse was empty: the work had left on a freighter, and all but one of the roboticists had gone. It was a hot day and we talked under fluorescent lights in an old meeting room with brisk air conditioning. He sat in an ergonomic videogaming chair and wore a shirt that he described as silky and nice against his skin. I mention these details because, as I learned in our conversation, Wolfson is highly tuned to physiological sensations, and in fact prioritises these feelings in his work.

Looking at Wolfson’s art, one could easily interpret his whole project as a sharp intellectual farce, but in our talk he was insistent on grounding his work in direct perception and metaphysical knowing. Much of his experience with art relates to proprioception, the kind of internal, tactile awareness that Maria Lassnig expressed in her paintings. All art, Wolfson told me, is “the validation of the expression of consciousness”.

Wolfson’s coverage in the press has often been thorny, a response to his success, his boldly direct remarks and the provocative tone of his sculptures and videos; but in our talk he pushed against this villainous persona and spoke of using his achievements to help out fellow artists. “It’s so hard being an artist,” he says, “and if people didn’t help me, I wouldn’t be here talking to you.”

Witnessing the Physical Self

ArtReview How did you arrive at the title Body Sculpture?

Jordan Wolfson When I look at art – my art, other peoples’ art and even just objects in space – I notice that my relationship to sculpture is actually not a relationship to a sculpture but a relationship to my body in proximity to another object in space.

AR The scale of it.

JW Yes. For example, when you see Brancusi’s Bird in Space, what part of your body becomes activated for you?

AR Maybe… the top of my head.

JW Interesting… your crown chakra. So looking at art is not intellectualism for me. It’s about physicality. It’s about the quality of my viewership at the moment of looking. But if the looking takes place over a gradient of time, then the quality of my viewership is based on my level of presence. When I say gradient of time, I mean, as I look at an object I move from right three-quarter view to left three-quarter view, and there’s a gradation of time and physical space as I move around the object.

AR So how does Brancusi feel to you?

JW I’m not sure. I’d just say that a successful work generally returns you to your body. I think there’s a trifecta of tension between a spiritual, intellectual and physical self, and when a sculpture becomes active, it’s able to manifest this feeling in a spectator’s body. So with Body Sculpture it’s basically about doing this over and over again.

AR So the ‘Body’ in the title is the viewer’s body.

JW Yes. Body Sculpture is just about witnessing the physical self, rather than witnessing a specific type of situation.

AR The name suggests that the work is part of a triptych with (Female figure) and Colored sculpture.

JW It is. But each one of these works has a different formal foundation. (Female figure) was like a portrait looking at you and away from you. Colored sculpture is about going between figuration and abstraction. And Body Sculpture is about going between personification and reification. It’s about returning the viewer to their body in a way that the other two could not do, because both of those sculptures were overridden by the fact that they could look at the viewer.

AR This work has no eyes, only body.

JW Yes.

Stuff the Intuitive Inside of the Practical

AR Is the performance of Body Sculpture telling a story?

JW There’s a loose narrative about humanity. It’s not a moral message about who we are as a species, but I think all the ideas it expresses are about basic things that the human animal does. There’s sex and ritual and identification of the self and joy and shame.

AR The whole spectrum.

JW It just happened that way. I think of my work like… when the principal asks the ten-year-old why he threw a rock, the boy says, ‘I don’t know’. Because he doesn’t know. His situation at home, his breakfast and his genetics all informed throwing that rock.

AR Did you throw rocks?

JW Yes. And it’s ok not to know.

AR Are you suspicious of intellectual engagement?

JW I am.

AR Do you like any art that stimulates you intellectually? Or for you, is good art free of that?

JW I believe it’s free of that.

AR So you would not call yourself an intellectual.

JW Not when I’m doing art.

AR But with such large projects, there also needs to be some kind of high-level conceptual thinking and pragmatic decision-making.

JW Being pragmatic isn’t doing art, but you can use it to set up situations where art can be made. A lot of time is dedicated to planning and organising time to be creative in, and for that to happen, technical issues have to be dealt with.

AR When you are working, how much time are you spending in a purely intuitive space?

JW I can do about three or four hours, but it varies, and if I’m lucky there are very brief moments of download. Mostly it’s a combination of searching and waiting. Sometimes it’s easy. Sometimes it’s hard. Sometimes it’s good to give up when it’s hard. Sometimes it’s good to work when it’s easy and stop on a high note.

AR How do you create a balance of the practical and the intuitive?

JW I stuff the intuitive inside of the practical. For example, if something is absolutely impossible technically or if there is a time or a financial limitation, then I accept it and find a solution intuitively, and I try to remain happy about this, not upset.

AR Sounds like solid advice. Any more of that?

JW If I were to give advice to another artist, I’d say that you need to have some type of technical talent, like you could be good at drawing but then you need to also have intuitive creative ability. You should try to develop both. But there’s also a third ability, that is to support and trust those other two abilities to do their work. If someone has too much technical ability, they might be cynical towards intuition. If someone is too intuitive, they might be cynical towards the technical. But you need both, and then on top of that you have to learn to trust yourself, and that isn’t something we are born with – or at least I had to learn it. So trust is the third skill I suggest the artist learn.

AR How would you describe your technical talent?

JW It’s not extraordinarily high but it’s above average. I was a fine draughtsman. Like, I was the second best at drawing through elementary, middle and high school. But when I got to RISD [Rhode Island School of Design, Providence] I wasn’t even close to the best.

AR Do you draw now?

JW Not as much. But the drawing modality translates to all sorts of things, like working with a skilled fabricator. It’s about communication. Like, if you were to direct someone to draw a face on a wall, it wouldn’t have a dissimilar result from you drawing on the wall yourself, except it might be subjectively better or worse. The problem is you need to be able to use this communication with the fabricator in replacement of the personal connection with the material, and it needs to become how you connect and reconnect with the material. It’s almost like a director and an actor in that you can allow the fabricator more or less agency in interpreting your requests. But ultimately it’s about communicating your ideas through language.

A Witness Holding an Object Up for Other Witnesses

AR I’ve heard you say that you dislike interactivity in art.

JW There’s different layers of interaction. I am sitting on a chair. Am I interacting with it? When a sculpture looks at you, is it interaction? When it makes you feel your body, is that interaction? What’s the difference between talking to someone on the phone and listening into another person’s conversation? These are all the different levels I have tried to negate crossing the threshold of in the work.

AR Where is that threshold?

JW It’s when something becomes pedagogical or literally interactive. If you need to functionally interact with something, I think the witnessing part of your mind turns off.

AR What’s an example of an interactive work?

JW In the early 2000s at the Walker Art Center [in Minneapolis] they had this AI dolphin you could talk to and it could reply. I believe that in that moment of interaction the art experience becomes extinguished. You might ask, what about Felix Gonzalez-Torres? You pick up a piece of candy and you put it in your mouth. But that’s not interactive.

AR Because it’s not responding to you.

JW Or remember Tino Sehgal’s Guggenheim piece [This Progress, 2006, presented at the Guggenheim in 2010]. The performers ask you a question. I would say Tino Sehgal’s work pushes interactivity more deftly than I have, in a more sophisticated, complex way. The piece allowed the viewer to stand at a passive threshold of listening and responding to the novelty of the situation.

AR You seem especially interested in the viewer. If your work had no viewership, would you make it?

JW No. I wouldn’t make it. I’m fine not working. I don’t need to express myself.

AR So art is a communication device for you. Body Sculpture isn’t complete until people see it.

JW No, it is complete because I am also the first viewer. That’s what’s ironic about it. I need the audience but I am also the central part of that audience. I am a witness holding an object up for other witnesses.

AR Your animatronic works suggest a life force within them. Do you ever believe that life exists within these objects?

JW No. But I believe that objects can distil and be vessels for the frequency of the maker. I believe that artistic practice is also spiritual practice.

AR Is your primary spiritual practice through art?

JW I think my initial motivation to have a spiritual practice was to enhance and develop my art. When you are a professional artist it’s like being an athlete. You have to work on intuition through spiritual practice.

AR Do you still consult a psychic for advice?

JW Not anymore in the same way. The advice was too limited. But I’ll pursue any avenue, really. I try so many things. You just do whatever you can, out of desperation, to help the work. It’s about commitment. For Body Sculpture I went through so much choreography. I threw out so much. I follow the 90/10 rule. I edit out 90 percent of everything. But I also add things back in that had been edited out… it’s good to realise that is part of the process too.

AR When you say choreography, who were you working with? Dancers?

JW Well, yes. But in the end I did it all with Mark Setrakian (roboticist and artist) and the stage team (Ted Marchant and Brennan Lowe). Someone would come in with credentials and I’d trust them, and want to believe that they could solve the problems in the work, but I wasted a lot of resources that way, not trusting myself enough. That isn’t to say they didn’t add to the work, but I couldn’t solely rely on them. In some ways they were too good.

AR You seem to push yourself to your limit. When I was here before, you were exhausted.

JW I’ve slept for a month since I last saw you.

An Unobstructed Distillation of Creation

AR Does this piece do something different than your other work?

JW I don’t think any art does anything different from any other art. The structural differences are topical, but all art attempts the same thing. It elicits us. But only if you are in the right mindset. If you’re stressed and in a bad mood and you see a wonderful artwork, you may not actually see it.

AR Same with your own work, I assume.

JW Yes. I make a mess of my work if I’m in a bad mood. I’ve spent so much time trying to get something back to where it was initially.

AR Do you only work in a good mood?

JW Yes. I won’t touch my art if I feel bad. Or I’ll get myself out of the mood by meditating or having a walk. I don’t want to look through pain to create.

AR But you’ll express pain in the work.

JW Well, that’s part of the shadow that must freely express itself.

AR Do you see yourself in service to other people as an artist?

JW No. I do this for myself.

AR Do you think your art helps others anyway? Maybe even simply by creating awe?

JW What do you mean by awe?

AR A sense of wonder that changes our normal perception of reality and allows us to understand ourselves and our environment in new ways.

JW Yeah. It’s like you go to Big Sur and you see the landscape and it fills you with this ‘awe’ and you wouldn’t change a thing about it. Or you see a great work of art and it fills you with ‘awe’ and you wouldn’t change a thing about it. Both those things are the same.

AR How so?

JW They are the expression of conscious- ness through material. Rock, water and dirt. Canvas, paint and wood. They are both the consciousness of nature. Waves and wind and circumstance made that cliff. And when the human being steps out of the way and lets the painting get made, you wouldn’t change a thing about it. But that’s what’s so hard as an artist. It’s about stepping out of the way. I mean, I used to think the mountain was beautiful because it was indifferent. But that’s a cynical way of looking at it. It’s beautiful because it’s an unobstructed distillation of creation.

AR Consciousness seems central for you. How do you define that word?

JW This is consciousness. [Gesturing to our conversation] Consciousness just blooms. It blooms in a rock or in a tree or in a lizard running over a cobblestone, or even the cobblestone itself. But I’m not the expert on this. Krishnamurti is. Ram Dass is. All I know is that when I’m looking at the mountain and when I’m looking at Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy, I’m looking at the same thing.

Jordan Wolfson: Body Sculpture is on view at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, through 28 April

Ross Simonini is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, musician and dialogist