“For centuries, we have named the vice in which we are held captive. The question is whether others are willing to know what we know.”

Since her groundbreaking study Scenes of Subjection (1997), American academic Saidiya Hartman has radically reoriented how we understand slavery’s afterlives. In books such as Lose Your Mother (2007), Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019) and numerous essays, she has theorised the liminal space between belonging and exile: the position of African Americans estranged from Africa yet constituted by its loss. In order to think through an archive of slavery that is marked by absences, silences and erasures, Hartman has developed a practice of ‘critical fabulation’, blending archival research with narrative invention to restore potential to the lives of those whom the record considers ‘minor’ historical actors. Her writing has become indispensable across fields from Black studies and feminist theory to literature and art, reshaping how we think about subjectivity, resistance and the ongoing structures of racial capitalism.

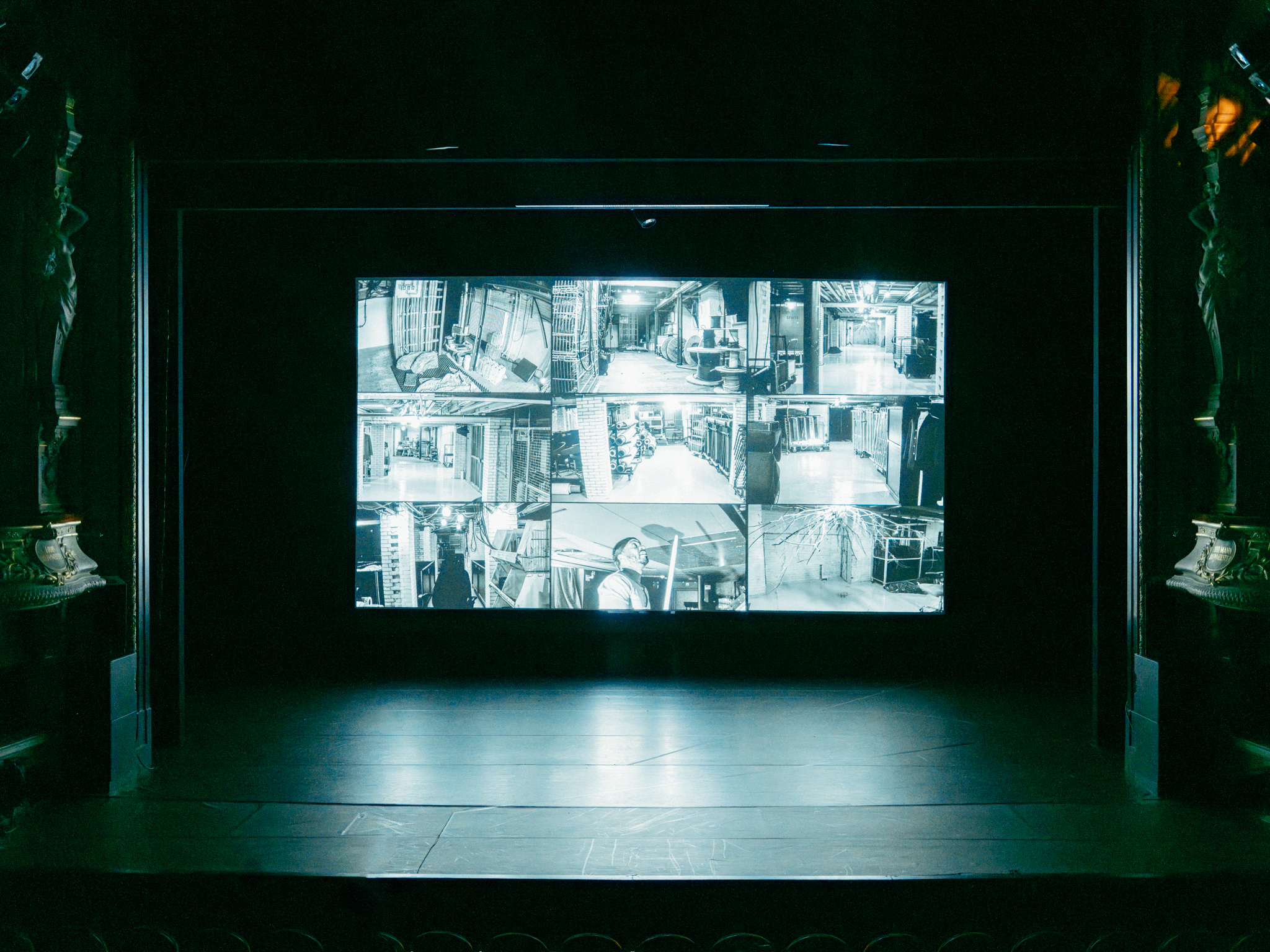

Her latest work, Minor Music at the End of the World (2025), takes critical fabulation to a new level in the form of a collaborative performance directed by Sarah Benson and presented by Hartwig Art Foundation in the Netherlands and inspired by a science-fiction story written by the leading intellectual voice on race, democracy and Black liberation of the past century, W.E.B. Du Bois. Best known for The Souls of Black Folk (1903), his magnum opus, Du Bois also wrote a science-fiction tale, ‘The Comet’ (1920), about the last Black man left on Earth following the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic. And it’s this that has shaped Hartman’s thinking in Minor Music. Structured in three movements – one drawn from her essays ‘The End of White Supremacy’ (2020) and ‘Litany for Grieving Sisters’ (2022); another, ‘Dead River’, newly composed; and a third remixing Arthur Jafa’s film Aghdra (2021) – the piece stages a choral, collaborative mode of thinking. With sections performed through spoken words and movement by artists including André Holland and Okwui Okpokwasili, it asks what kinds of dwelling, refusal and collectivity might emerge in a moment marked by ecological collapse, authoritarianism, human fungibility and the dismantling of academic and artistic freedoms. ArtReview caught up with Hartman in advance of the work’s world premiere at Internationaal Theater Amsterdam.

Theory into Practice

ArtReview You have referred to Minor Music as a kind of ‘chorus of the wayward’. I hear echoes in that of your past work on ‘fugitive being’. Could you describe the new work, and what you set out to do with it?

Saidiya Hartman The work consists of three movements. The first establishes a conjunction between the present and W.E.B. Du Bois, who a century earlier, in ‘The Comet’, described a US defined by racialised violence, segregation and the brutal rule of capital and elites. There is also the shadow of the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic. What would it mean to imagine the end of the racial order? We could say this ‘ending’ started in 2020, and was arrested. The stranglehold of authoritarianism, capitalism, white nationalism and the glorification of the heroes of slavery and settler colonialism has intensified in the present. So, the question remains: what does it mean to imagine the end of this order? To address it, Minor Music shifts between Du Bois’s text and mine – with the threat of other extinctions presented by the climate crisis – which is another dimension of the end of the world.

AR Writing can sometimes diverge from the author’s original intent when interpreted by others How is it to watch performers use their voices and bodies to interpret your texts?

SH The texts, ‘The End of White Supremacy, An American Romance’ [2020; Hartman’s text about ‘The Comet’] and ‘Dead River’ [2025; developed by Okwui Okpokwasili in collaboration with performers Bria Bacon, Audrey Hailes and AJ Wilmore], are themselves collaborative works, informed by a wide array of theorists and writers: a round of utterances. That defines the choral nature of this work. Even when my name is on the page, many voices are present. The performances don’t illustrate the text, they articulate it, enriching and transforming its meaning. This is the dynamism of the process – it remakes the text. So the work keeps evolving, and I love the collaborative character of it. I’m a contributor, but there are other makers – performers like André and Okwui, whose practices are extraordinary. I have a particular attunement to language: the power of the sentence, the movement of a paragraph, the drama of a page. But it’s very different to hear your words uttered by someone else. They become something other; it’s a beautiful, dispossessive experience.

It is crucial to state that what I’ve written is not a play – it is performed discourse or choral utterance. Okwui’s performance practice, which involves extended, physically demanding movement and voice, pushes against the grain of theatre: what does it mean to perform and embody discourse, which is different than a character‑driven play? Watching André, the magic is witnessing a classically trained actor transform critical thought into flesh and blood, and make concepts into an autobiography of the last Black man on Earth – these encounters with the world engender ruptures in our existence and trigger radical shifts in thought.

The End of an Era

AR I love that picture of collective study and collaboration. It reminds me of the feminist decolonial scholar Françoise Vergès, who has spoken to ArtReview about how collaborative re-imaginings of the museum, too, are vital. Yet Vergès also warns of such attempts being at risk of institutional capture. Do you find performance can resist that tendency?

SH Performance can of course be extracted and repackaged, but it’s different from the way an art object holds capital or can be collected by individuals. The relationship with elite institutions is always tense: a work with radical aims can paradoxically enable institutional reproduction. At this moment I think it would be very difficult to produce Minor Music in the US. Work that examines Black women, slavery, feminism, gender, anti-Blackness, climate, environment and capitalism is being prohibited and defunded as ‘anti-American’; the people who make such work are described as ‘the enemies within’. There have been calls for the arrest of Marxists and communists. We’ve entered an authoritarian period in the US. It is a revanchist, white-supremacist project that is hostile even to canonical Western thinkers such as [Sigmund] Freud and [Max] Weber. Sociology has been eliminated from the curriculum of many state universities. Critical frameworks devoted to examining power, structures of inequality and the forms of social difference created by extreme domination, precarity, fungibility and accumulation are being prohibited. The goal of this fascist authoritarianism is to resurrect an order of values that provided the foundation of slave society – the subordination and fungibility of Black life, futurity secured by extraction and command over the dominated, and freedom as the entitlement of propertied white men. There is a war against everything that doesn’t uphold the values and views of the administration. Objects are being removed from the museums; archives are being eliminated and destroyed. At present, we are in a struggle for basic academic freedom. In the US I’m not doing something fashionable; I’m involved in a project subject to eradication.

AR Thinking on the end of a world order can be frightening as much as it can be generative: we have seen it spark violent reaction from rightwing pundits and ordinary people alike. Indeed, times of revolutionary rupture can also be bloody and uncertain. Does the work also engage with mourning and uncertainty – the fact that we can’t go on as we are, yet we don’t have one single, shared vision of a post‑racial‑capitalist and ecologically healthy world?

SH The second movement is structured by that open question. What does it mean to find a way when the essential coordinates are unknown? Is human existence itself an open question – are we only a platform or threshold for other forms of creaturely life?

AR That asks us to let go of our anthropocentrism, too.

SH Yes. Think of the destructive character of ‘man’ – the history of ‘progress’ from slingshot to atomic bomb. Attempts at reform often inaugurate other orders of violence. I’m involved in practices in the now, practices for the time being: assemblages of care and collectivities that minimise harm and create other modalities of dwelling. There’s no guarantee for the future, but practice need not be directed by assurances regarding it. If we measured liberatory movements only by outcomes, we would misread them and minimise their accomplishments. Frantz Fanon notes that those who fought against colonialism often never lived to see benefits of their struggle.

Revolution as Housework

AR We often crave outcomes, rather than thinking long-term in that manner. What forms of relationality and practice can we pursue in our communities now, to pave the way for changes we may never see?

SH Many are already involved in these changes: free schools; mutual aid and exchange without money; radical collectives and land trusts. Many are refusing, by boycotting companies of billionaire technocrats aligned with the authoritarian project or that have adopted anti‑DEI agendas. Aspects of everyday practice can escape capture. Of course there’s no guarantee about what they will yield. When I was an undergraduate, we all wanted to be young revolutionaries. A teacher, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, admonished us: ‘The revolution is like housework – you have to do it every day.’ It is unfinished, incomplete, ongoing.

AR You’ve written about ‘ethical listening’ in Scenes of Subjection. Did you draw on that here? Who is the listener in this work, and what kind of listening do you hope its audiences practice?

SH The radical hope is that audiences will listen. I teach a course called The Frequency of Black Life, about the elements of Black life as figured sonically. Listening presumes the other and is a context of exchange. In this piece, ‘minor music’ – as sounded – signals change or a state when something has fallen away. The work explores the critical work of the minor key: not stepping into the major or proper, but embracing the dissonant work of the minor, as in, minor music, minor figures, minor literatures. The movement score embraces opacity and incompleteness. The sound score and the choreography of the physical performances together offer plural and divergent accounts of work and world. Minor Music is an invitation to gather and think collectively and it compels or obliges those experiencing the work to consider if or how they can receive it.

Absolute Violence

AR Much online commentary casts the piece as primarily concerned with voice and refusal in Black social life. While that may be the case, do you also see the work connecting to global struggles that we’re all bound up in under a racial and gendered capitalism?

SH The performance opens with a speaker thinking about their formation within the global system of capitalism. It’s a world system; our histories are transversal. US empire’s reach means what happens here is felt globally. Systems of racialisation, anti‑Blackness, coloniality are global – the structures that seek to uphold them learn from one another. For instance, the Nazis built their racial laws on US models. Hitler admired the US racial order. The question ‘what does it mean to exist at the end of the world?’ is shared. We grapple with it in geo-specific places, as sentient creatures on Earth, with varied beliefs about inhabiting land and time.

AR As capital seeks further accumulation and many governments grow more authoritarian, people around the world have seen their life expectancy and quality plummet. Many on the left hoped, at that point, a shared sense of cross-class and cross-racial solidarity would emerge, but that has not proven to be the case.

SH Those in the metropoles of Empire are catching up to existential questions others have carried within themselves for decades or centuries. The limits of states- and rights‑based politics demand planning for other modes of existence. The US state has shed any pastoral duty, becoming extractive and predatory – becoming absolute in its violence. In the meantime, private ‘solutions’ emerge: those with several hundred thousand dollars can now buy homes in eco‑enclaves that have biodynamic farms and practise organic living. The alternative is already being commodified.

Welcome to My World

AR That picture seems like a new form of apartheid: rather than regreening the Earth, creating gated liveable zones while the majority of us deal with climate fallout.

SH Figures like [Elon] Musk and [Donald] Trump are saying the quiet part out loud, defending a vertical order where some lives matter more than others. The hierarchy is taken for granted. In a liberal regime one had to mask that fact; there’s no need now. The apartheid order of the disposable, precarious, fungible and incarcerated grows. Policies blatantly funnel wealth upwards. Black people arrived at citizenship belatedly. The rights most Europeans took for granted in the nineteenth century, we gained in 1965: in my lifetime. Mostly, we [Black people] have lived under racialised enclosure and terror: that’s been the norm. Many Americans believe in US exceptionalism and can’t imagine their country sharing the fate of others – hence the absence of millions in the streets.

AR In a sense it is exceptional – as the imperial core, it was shielded from this fate a little longer – but the brutality is the same. What kind of hope may lie, as Minor Music suggests through its performances, in acts of imagination?

SH The band‑aid is off, but I don’t expect those newly seeing to be transformed. Those made comfortable by wealth and white privilege are experiencing threatened rightlessness and precarious citizenship for the first time. We say, welcome to the world. I hope this levelling, the nascent sense of a precarity-in-common, will eradicate the racial order that Minor Music stages as ending; but in the US, recognition of shared disposability has also catalysed a white nationalist project. Liberal pundits treat the present as an exception, and pine for a golden age – their own MAGA imagination – an age when the US ‘kept the peace’. They embrace an enchanted view of the foundations of the American Project, ignoring racial slavery and settler colonialism, and try to counter Trumpism with a delusion of their own. The privileged, the comfortable, don’t grasp the constitutive exclusions of liberalism.

AR Could this realisation – that state‑bestowed citizenship has always had exceptions and hierarchies – be a precursor to rethinking ‘at the end of the world’, personhood beyond the state’s racialised and gendered markers of recognition?

SH That’s a beautiful – and for me hopeful – formulation. In the US, we cannot forget that ‘Black’ is a structural position – disposable, subject to gratuitous violence and state terror, subject to diminished life chances, at the bottom of wage scale and the social order. For a long time, many Black people have considered themselves stateless: think about Malcolm X’s petition to the UN, or Paul Robeson and William Patterson’s petition charging the US with genocide. Du Bois died in exile, renouncing the US project. For centuries, we have named the vice in which we are held captive. The question is whether others are willing to know what we know, whether the formations of knowledge and power that enabled this capture can be expected to produce something else – or whether we must rethink existence, world and Earth from the ground up.

From the November 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next: How to decolonise the Western museum model? Françoise Vergès advocates disordering, decentring and dispersing it