“When I’m out and making pictures, I try to be completely blank or unaware”

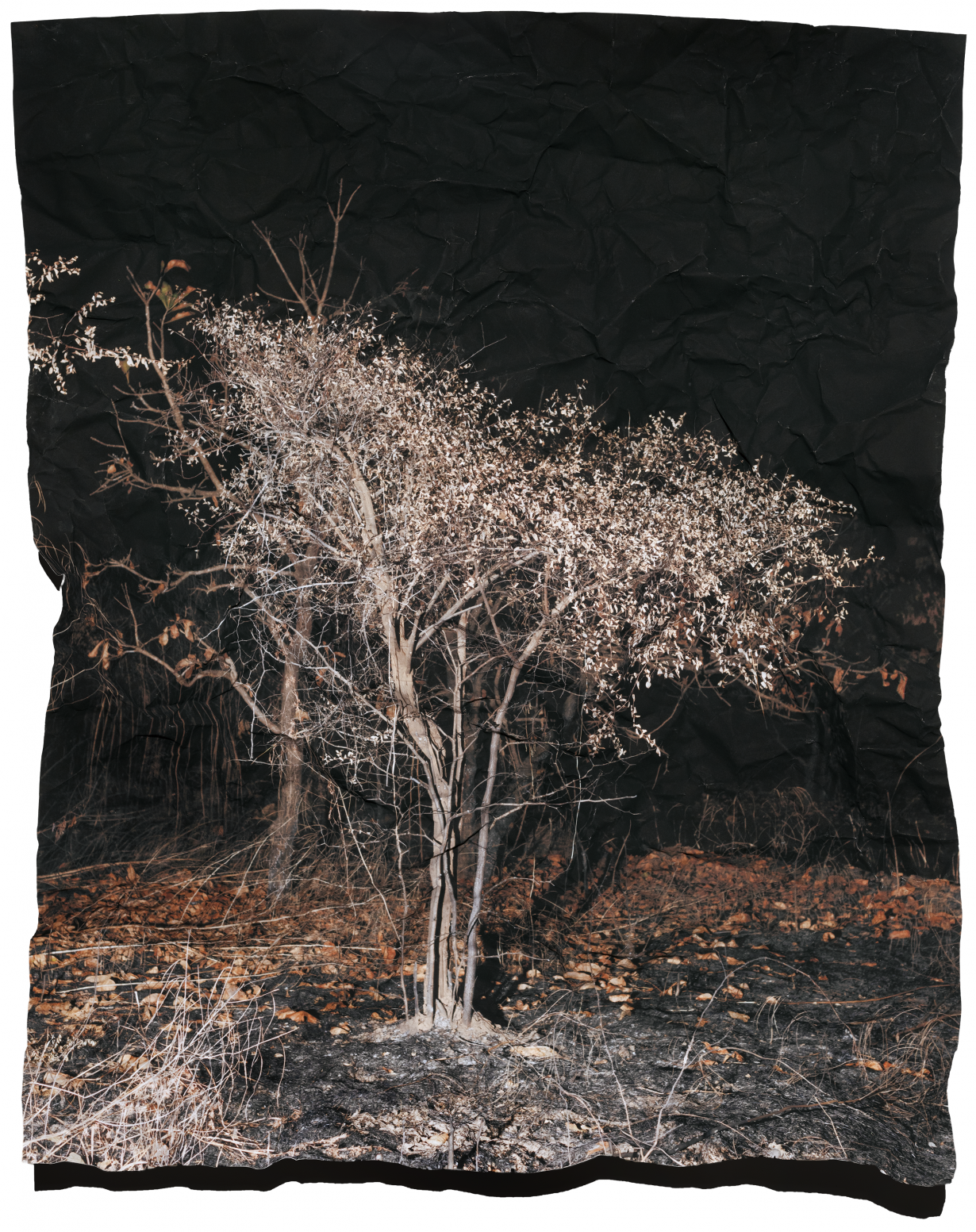

Tenzing Dakpa is a photographer based in Goa. He came to prominence with his series The Hotel, which he began in 2014/15 and published in book form in 2020. The series (shown at the 2022 Kochi-Muziris Biennale) shows the photographer documenting his parent’s hotel, which was also his childhood home, in Sikkim, Gangtok. Having helped out with the business as a child, the artist was curious about revisiting the site now that he had no work to do there, and to explore both his identity (a second-generation Tibetan) and that of his family. This month, in his first solo exhibition at Experimenter in Kolkata, he presents two new series of works: Manifest (2023), which documents the aftermath of manmade fires in North Goa, and Weather Report (2023), photographic installations that document the natural landscape in relation to time, climate and seasonal change.

Get Out

ArtReview Asia Did you want to be a photographer from a young age?

Tenzing Dakpra No. It started with moving to Delhi in 2004 and travelling across the country. I was in an undergraduate graphic-design programme. The college was really horrible, so I used to travel around the country backpacking and taking pictures. It started there and this idea of being in Delhi and being a northeastern boy, a Tibetan boy, trying to figure out his own identity within the place.

ARA Was that desire to figure out your own identity your own desire or one that other people projected on you?

TD It was definitely something other people projected onto me just in terms of racist laws and a certain area within Delhi where you have to go and live. You cannot be outside that area because you just live as a community there. There’s all of that, essentially. There are places you go to. It’s understood that you’re supposed to go there, you’re supposed to have that. It’s safe. Also, it says something about the place of what they think of you, if that makes sense.

ARA Do you think that’s getting worse?

TD I left Delhi very much for those reasons, and I think it’s still there. It’s still aggressive and it’s still a thing, but again, there’s like my brother being lynched or me being stabbed. There were incidences in Delhi that really made me reconsider my life and take it more seriously in terms of, ‘Stop fooling around, focus on your work and try and get out of this place’.

ARA What brought you to Goa from Gangtok?

TD After I finished my master’s in Providence, Rhode Island, I lived in New York for a year. Then in 2017 I moved back to India. I had lived in Delhi for ten years before I moved away to the us, but when I came back, I just could not get myself used to living there – it was too hectic and I also had a lot to unpack from the programme. A bunch of friends were moving to Goa and said, “Why don’t you just join us?” I went for a visit, liked the quality of life and I stayed on.

ARA Do you feel like an outsider in Goa?

TD Very much so, yes.

ARA Your new exhibition features two bodies of work that relate to Goa…

TD I’ve been working on it for the last three years. I have a studio in Goa, in a big old Portuguese house. We put on small exhibitions there, so the work has been shown in small parts as it was developing.

ARA Your new work focuses on landscape in a way that’s quite different from series such as The Hotel, in which signs of human presence are obvious and everywhere.

TD In some ways photography has always been a way to explore my immediate environment. I think that happened organically. Especially after Providence. There I had this habit of photographing every day, just going out on long walks and taking pictures. I tried to maintain that in Goa, which is generally a beautiful place to walk around: it’s got beautiful light; the seasons change; it’s very rich in terms of the forest and the biodiversity. But while the works are portraits of landscapes in some ways, and devoid of people, they are nevertheless about the presence of people.

ARA Mainly in a negative way?

TD I don’t think about it. That’s the thing. When I realised that I could not unsee the development and industrialisation that was happening around me, I stopped the project. When I’m out and making pictures, I try to be completely blank or unaware, and I’m just responding to forms and shapes and light and colour. It’s more exciting that way.

ARA Are there particular scenes or scenarios to which you’re more attracted?

TD Yes. There’s a series called God’s Gift [2023], which also focuses on these types of human-affected landscapes. It’s more directly related to development projects, or this idea of extra paint being painted over a tree trunk. It’s got a sense of humour. Coming from the Hotel work, which looked at my parents working, there’s this idea of what we live with. And you’re trying to make sense of that through pictures. That’s what I was getting at with God’s Gift: there is always a push and pull between nature and your habitation, basically.

ARA I guess in The Hotel, for instance, you’re attracted to the kitten, Dungkhar, and you’ve said before that the project began in a way as you were following this new presence. This interest in the nonhuman continues in the newer works.

TD Yes. There’s a certain kind of remove – you’re part of what’s around you, but there’s a certain distance that you’re maintaining in some way.

ARA How important is keeping that distance as a photographer?

TD I think it’s very important to do it through the images as opposed to the images illustrating your idea. It’s the other way round, where the images are like a story in some way showing you where to go or what to do next.

ARA Is it generally after you’ve taken the photos that the project itself takes a form?

TD It shapes up, yes. It’s like you’re making images and then you identify a few things that prick your interest. You see a certain kind of potential in it and you develop that further, but never in a way that’s articulated in the sense of: ‘This is what it’s about’. It keeps going and suddenly you stop and you try to figure things out: ‘Maybe I need to stop and show it to someone’. Then you try and articulate, formulate the idea, and think about it. It’s in retrospect.

ARA You’ve previously said of The Hotel that part of the idea behind that was finding out who you and your family are.

TD It was a premise that I set myself to get into it, which was just something I told my dad, “Dad, do you know I want to figure out who we are as people just in terms of trying to figure out my relationship with this place now. Because I’ve moved away and I’m not really part of the family.” I can hear, as I say that, this idea of articulating or explaining what I’m doing before I actually do it. But in the case of The Hotel, it had to be articulated – some sort of introduction. A push needed to happen for me to receive and let them do their thing.

ARA Were there any surprises in terms of the answer to that question about who you were?

TD No. But I think it made my position as a photographer very clear. It helped me acknowledge or adopt this person I had become: who’s a photographer who lives outside in the real world and comes back once a year and photographs his dad’s garden. Sometimes.

Saved by Pillows

ARA What did your parents think of the series?

TD They thought the pictures were funny. I think it was a very simple and direct response in terms of how they were making fun of each other, in terms of how they looked at the pictures, how they were looking in the pictures, or what they were doing, and that they are very sure of their own ideas in terms of who they are, what they do.

Right now I’m learning embroidery from my mother and I’m making some things. She looks at my embroidery and she sees that there’s a very different way of approaching what we each make, and the way we explain and describe things. My parents are very sure of how they do it. They’re not judgemental or anything, they’re just sort of…

ARA …they have a sense of right and wrong ways.

TD Yes. But they’re not judging me. Basically, growing up in the hotel also, or seeing my parents work, you realise that there’s a lot to do with the hand. There’s a lot of labour that goes into making. My brother is basically making leather bags all the time. My mom is doing embroidery all the time, and Dad’s working with bonsai all the time. I work with paper and prints and I make books. I’m making different maquettes. I’m asking my friends to come over to my studio and we produce books together, trying out different kinds of binding, making different kinds of paper profiles. Even with photography, you’re going out into the world and you’re being out there alone and sometimes you catch yourself realising what and who you are. There is that work that involves just being out there photographing and looking at the real world.

ARA Some of the new works are printed on paper that’s then crumpled. I guess that makes them feel a bit more handmade.

TD There’s the expectation that photography should look ‘real’. And that’s the curse and the gift of photography: it’s too close to reality. I come to a point where I’m exhausted making pictures. Then I’m trying to do something else to upend the work in some way, to change it, maybe materially, maybe formally. With The Hotel, in a less-conscious way, it was the images of pillows that did that for me. They added a certain kind of abstraction. They were formally very different from the others.

ARA In the new work, I think also it maybe forces you to look at the print as an object in itself and not an image of something else.

TD I think it has in some way transcended or transformed the materiality of what a print should look like, and it begins to be something else. It could have been a fabric. It could be more. It’s a text.

ARA It’s the same with the bigger prints that are made up of smaller prints.

TD Some of these things are coming out of my own limitations – having a smaller printer and stuff. This idea of the grids was something that happened with this habit of wanting to make larger prints with a smaller printer. The more I thought about it, it was in some way like when you’re dividing land: you can cut up different pieces – small pieces of land – and you can piece it into a large chunk of land, divide it back into smaller pieces. But the prints also move, they curl, they do their own thing.

ARA What happens when someone buys one of those prints? Are you encouraging them to let it curl and move?

TD Honestly, I’ve not really thought about it. It’s a boxset sort of a thing. There’s an instruction guide where you can actually put it up with the magnets. You can fasten it from all four sides if you want to.

ARA You’re happy for people to make their own interpretations?

TD Totally. It’d be nice to see.

ARA With the series Manifest, it’s in the aftermath of a fire or a series of fires. Has the human impact on the environment in general become a subject?

TD I guess, again, it’s just looking at people’s presence within landscapes of environment and what they do, but also photographing it with a flash and with the light receding into darkness. While you’re recording the subject in itself there’s also something transformative that happens along the way. There is that interest in what happens once you photograph it and what it then becomes.

ARA Action without all the actors.

TD Yes. That was the thing. Like I said, like with God’s Gift, once you realise that the scenes trace the effect of human presence and you can’t unsee it, then it stops becoming exciting to me. It has to keep moving.

Goat or Sheep?

ARA The text that accompanies the show mentions elements of Buddhism being present in the work. To what extent is that something you’re thinking about when you take the photos?

TD For me, I think of it as something that’s a parallel philosophy or an idea of how I work with images. As a photographer, you photograph something and you take it out of its context and put it next to something else. You give it another meaning, try to shape it. You try to guide that meaning and give it a form, whether that is in a book, a print, a poster or maybe as a zine, whatever, but I think it changed.

I like to think of the photographic process as taking something and guiding it to make it something new. As relying on what it is given to you and making something else out of it.

ARA Can you be more precise? Does the subject have to be something that surprises you, for example?

TD Yes, definitely. It has to become more than itself in some way, like surprises me materially, sometimes just in terms of the rules of photography, in terms of what it’s becoming basically.

ARA To what extent do people have to know about the Buddhist narrative when they’re looking at the work?

TD It’s just something that I think about and practise myself. When it comes to the reading of the work, people who are interested in those things can pick it up. It’s a way to think about my process. That applies to all things, not only Manifest.

ARA In a sense the Buddhist elements are part of your identity. Does that play out in other ways in terms of how people look at your work?

TD In the sense of growing up as a second-generation Tibetan? Not really, but there is an element of that. I made a series called Ari/Ramaluk [2021]. Basically, what that means is something that’s ‘neither goat nor sheep’ [ra means sheep, luk means goat]. It’s a particular slang term used to describe Tibetans who are not really Tibetans. Like I said, our culture is rooted, but in some way, growing up in India you’ve drifted away from your own culture and you’ve become something else.

It was made apparent to me in a very direct way with a work that I did called Vez and Me [2005–11]. I was photographing my girlfriend then. We were living in Delhi and the images are of our seven-year relationship. I made it into a slideshow series and showed it in a Tibetan youth hostel. They were looking at those images and they were saying, “This does not look like Tibetan work”. They just saw this young couple in Delhi photographing each other. Which was the work. The reference of visual culture within Tibetan identity was very different as opposed to what I was doing. At least, that was the reality for me. I identified that idea with the term ‘ramaluk’, which means you’re existing in the middle basically, neither this nor that, you’re always shifting.

Weather Report, consisting of two new bodies of work by Tenzing Dakpa, is on view at Experimenter – Hindustan Road, Kolkata, through 27 July