“With or without anger, with or without sadness or depression, I have always been an artist. That’s the constant”

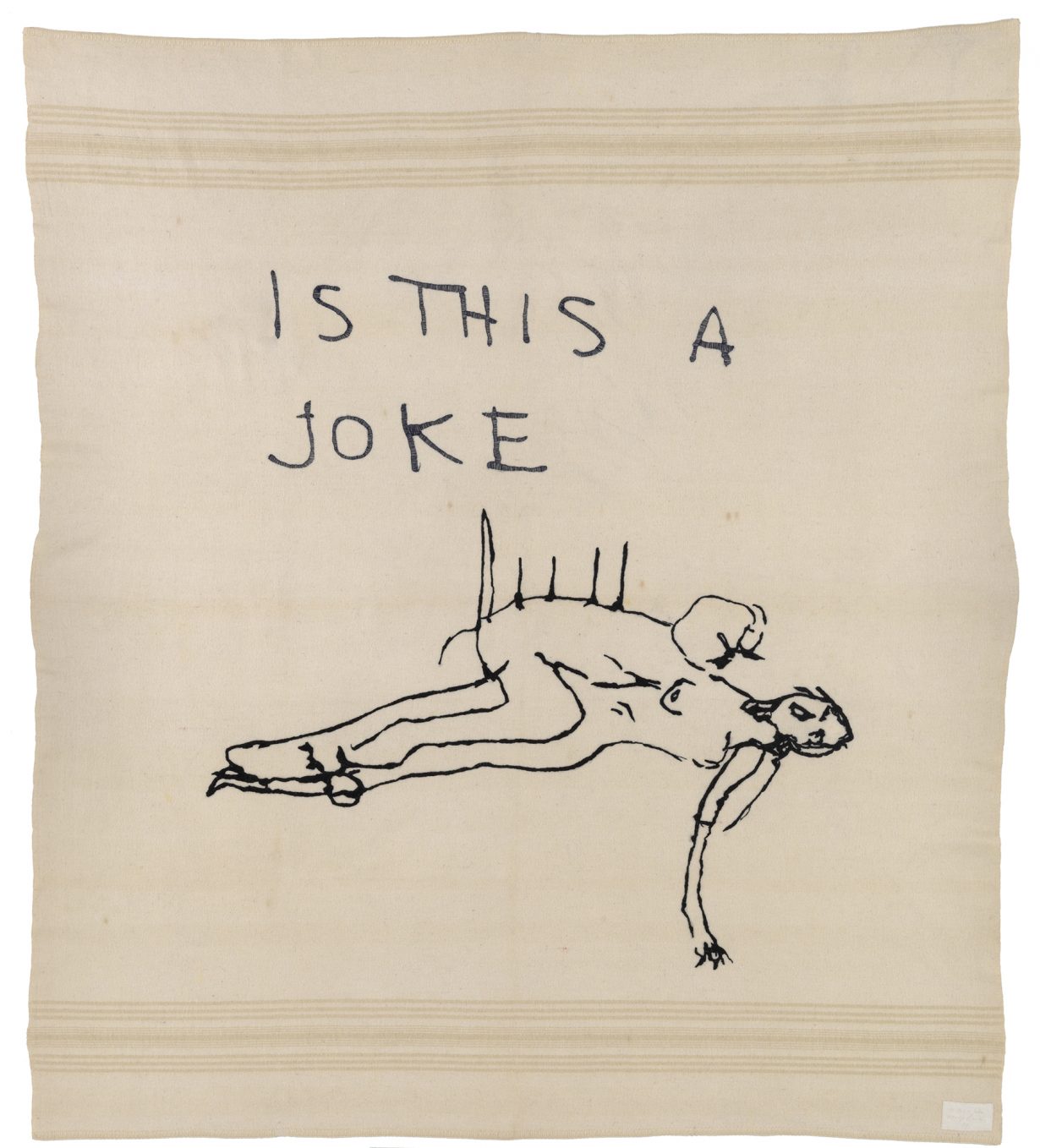

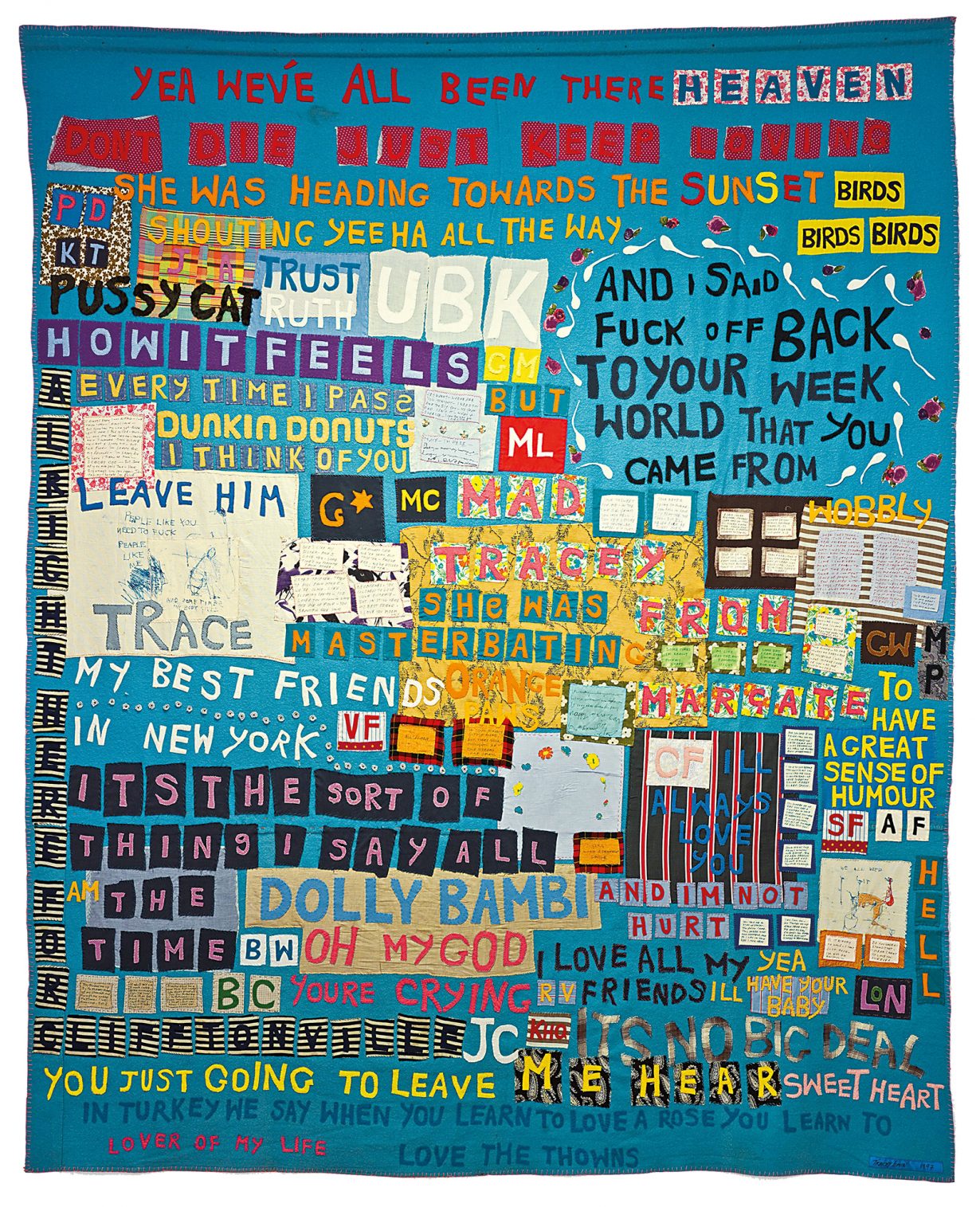

Tracey Emin is a romantic. This is a trait that has often been eclipsed by the mythology surrounding her name. For decades she has been framed by the sharper edges of her confessional, confrontational work: the provocateur who furiously prised open the female body and pinned its vulnerabilities to the wall, the artist who turned the bed, the body, the bruise (literally and figuratively) into public language. Rage-fuelled and drawing on her own experiences, Emin spotlighted such issues as rape, abortion and domestic abuse in the early 1990s, most famously through textile-based and installation works. Yet beneath the notoriety that shrouds this British artist lies a painter of longing. Besides those works that dealt with violence against women, Emin was making, and continues to make, work that is diarylike: self-portrait paintings (after several years’ pause she returned to the medium during the late 1990s) in states of passion as much as in pain, neons that take the form of her own handwritten, often wistful musings about relationships, installations and sculptures based on domestic interiors that verge on a kind of abstract figuration – rooms and wooden structures that feel as though they teeter on the point of collapse, signalling, perhaps, an internal destruction. Love, in its various conditions – euphoric, devotional, abject, daring, desperate – has been her most enduring subject.

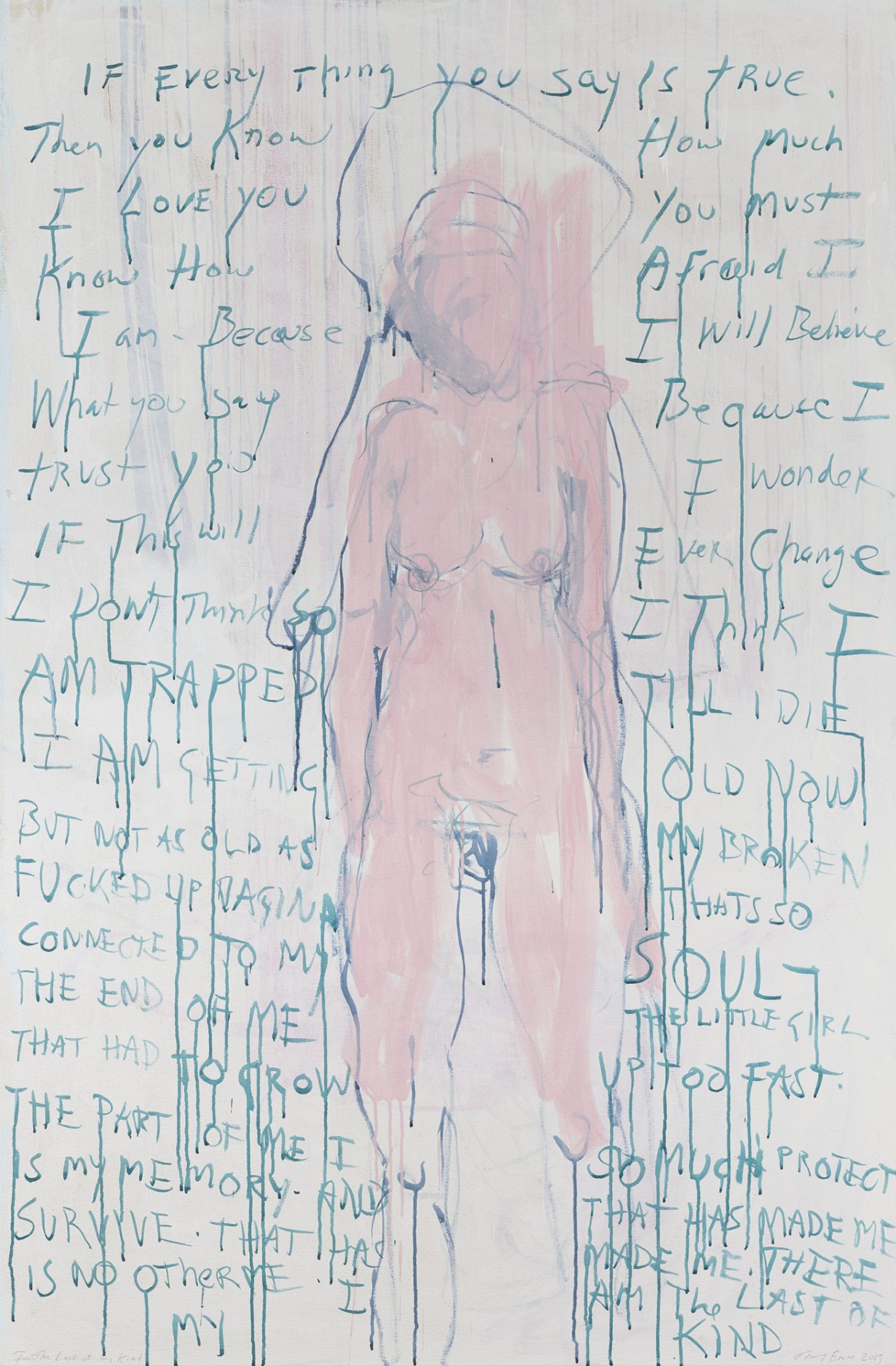

In recent years, this tenderness has come further to the fore, explored in paintings, bronze sculptures and photography. Following her mother’s death, in 2016, from bladder cancer, and then her own diagnosis with the same illness in 2020, which resulted in extensive surgeries, the stakes of exposure, both public and personal, shifted. Survival recalibrated her work. The figures that populate her canvases – sometimes two bodies intimately entwined, and sometimes her own alone – now seem to flicker at the edge of presence and disappearance: more often than not, these are painted in bright red, pink or dark blue outlines and loosely held against background washes of pale pink, chalk white, diluted blues. Beds remain a recurring motif, but they are quieter spaces for recuperation, for grief and for tangling with the limbs of another. The body is no longer only a site of rupture; it is desiring, hopeful, persistent.

Now based primarily in Margate, where she founded TKE Studios and works within sight of the sea, it seems as though Emin paints with a sense of horizon, of hope. At a new, largescale survey at London’s Tate Modern, the arc of her oeuvre feels newly legible. What emerges across the decades is not simply provocation, but a sustained commitment to intimacy: to the risk of sincerity, asking what it means to love, and to continue loving, in a body that endures.

Sex and Solitude

ArtReview You’re in bed – and you call it your boffice?

Tracey Emin Well, my friend Liz – she’s not very well, she has cancer – and I, we’ve just started a film company together with John O’Rourke. Liz works from her bed and I’m always in mine, and we needed a name for the company. She suggested Boffice Films, which is completely ridiculous. People always ask, “Why boffice?” But I think it’s really funny. I said to her, “Watch, in a year people will just say, ‘I’m in my boffice’”, as if it’s the most normal thing in the world.

And since I had cancer, I spend a lot of time in bed. I get physically tired – deep fatigue. I’m shameless about it. So the person who made My Bed [1998] now spends an inordinate amount of time in bed. It feels very apt.

AR I suppose it’s not something you’d ever have imagined – conducting interviews from bed.

TE No. But I’m quite open. I’m candid. I could have got up half an hour ago, washed my face, put on some makeup, worn a proper bra, sat in my bright white kitchen and given you a completely false impression of myself. But I didn’t want to do that. This isn’t a formal conversation – and you really couldn’t get more informal than this.

AR You must be incredibly busy right now.

TE I am. I’m doing a show at Carl Freedman Gallery, Crossing Into Darkness. It was meant to happen in November, but everything got delayed. In a way it’s better now. It’s taken my mind off the Tate show.

AR Are you nervous?

TE Of course. It’s on a really big scale. It’s the biggest thing I’ve ever done. Not many British artists show at Tate Modern, especially in that gallery [Eyal Offer Galleries]. I always thought it would happen in ten years’ time – not now.

AR What do you think would be different in ten years?

TE I might not be here. But also, the longer you leave something like this, the more choices you have. You only get one go. If I’m doing it, I want to do it as well as I possibly can. I don’t want to look back and think, we should have done this differently.

I had a big show at the Strozzi in Florence recently, and I loved it. There was nothing I would change. That’s rare. As you get older, that should happen more. You can tweak things, but if the show communicates what you want – that’s the most important thing. That show was about sex and solitude. I did that.

Being There

AR Hearing you talk about time is interesting. I’ve encountered your work at different moments in my life – as a teenager, in my twenties, and now – and throughout that time, the way I relate to your work has changed significantly. Has your own relationship to time changed the way you see your work?

TE Everything is different now. My life is unrecognisable compared to seven years ago. It’s almost as if I’ve been remade. But the essence is still there – like a candle. The wax changes shape as it burns, but the wick remains.

Margate has changed. My body has changed. My tastes are evolving. I don’t feel like the same person – or rather, I feel more like the person I was meant to be. When I was younger, and then again in the middle of my life, I think I was less myself. I was distracted – by attention, by external noise, by celebrity. I resisted a lot of it, but it still had an effect.

Now I’m not reactionary at all. I’m just being. That’s a completely different state.

AR Did that shift come through illness?

TE Yes. When you’re that ill – when death isn’t a vague idea but a probability – everything changes. It wasn’t ‘I might die’. It was ‘I’m likely to die in six months’. The odds were stacked against me.

I decided I wasn’t going to think about death. Death looks after itself. I focused on living. I didn’t go to therapy, I didn’t prepare for dying – I prepared for living. And something extraordinary happened. I used to carry a lot of anger, seething anger. Now it’s much less. When it comes out, it’s still strong, but it doesn’t dominate me. I’m calmer. I’m happier – even when I’m sad, I’m happier than I used to be.

Cancer wasn’t a near-death experience – it was a probable-death experience. And it taught me not to waste time. I don’t drink anymore. I don’t get hangovers. I’m focused. When you’re focused, big things are easy. I don’t want to sit there thinking, ‘One day’. If I have an idea, I do it. That’s it.

Bad Paintings

AR How does all of this – illness, recalibration, this sense of a second life – enter the studio?

TE I believe in alternative energies. When I’m making a painting, it isn’t just about the picture I’m making. When I was younger, I didn’t stop painting because I didn’t believe in it – I stopped because I couldn’t get what I believed through painting, because I was just making pictures, and I wasn’t happy with that. Now I’m not painting pictures. I’m trying to trap something – a life force. The energy comes through me, and if I’m lucky, it gets caught in the canvas. If it doesn’t, the painting is no good and I paint over it. And then it might come again.

AR That’s interesting, because – and this is a total cliché – I would say that your paintings vibrate in a way that feels alive. What, exactly, that feels like depends on the viewer.

TE It is a cliché. But it’s also true. That’s why art matters. Out of everything humankind has done, art is one of the greatest things – because it exists for no reason other than itself. Design has a function. A chair might look beautiful, but if you can’t sit on it, it becomes sculpture. Art, in its purest form, has no practical purpose. It’s like nature. It exists because it exists. That’s why I always say: how much stuff do we actually need to put into the world? Some artists are purely conceptual because they’ve decided the idea is enough – the object isn’t necessary. And that’s valid. Take Donald Judd: the simplicity of his forms is about purity. But he was also a hoarder. He loved objects. His whole life was about putting things into order. In my own way, that’s what I’m doing now too – putting my life into order.

Big Paintings

AR There’s always been a sense of precision in your work – especially in language. Even when the paintings feel volatile, the titles are exact.

TE Nothing is ever Untitled. If something doesn’t have a title, it means I haven’t found it yet. Titles matter. I’ve always thought of my mind like a filing cabinet. I go into it, open a drawer, a file comes out, and the work is made. There’s consciousness, calculation, boundaries – even if they’re subconscious. When I paint, I know the frame I’m working within. It might be a figure lying like this, a leg positioned like that – there’s a structure holding it all together. And within that structure, I have freedom.

Sometimes it’s incredibly physical. I’ll be working on five canvases at once, like a banshee, throwing paint everywhere. Other times I start with a drawing, paint over it completely, then paint again. When it’s finished, it might look incredibly simple – a linear figure on a flat ground. But when you lift the canvas, it’s heavy. Five layers of paint underneath. People don’t see that, but it’s there.

AR Do you still feel the energy of those layers, even when they’re buried?

TE Yes. And sometimes they refuse to disappear. Ghosts come through. I did a painting recently of someone kneeling – it was really kind of nice and good, prayerlike. Then I saw it from the other side of the studio and realised the legs looked like someone lying down, legs wide open. So I repainted it, changed the body, removed the praying figure. But the figure keeps coming back. Now the painting looks like someone lying naked, facing a doorway. From another angle, you still see the praying body. The meaning keeps shifting.

AR Does that ever make you doubt the work?

TE Doubt is part of it. But it’s not doubt in the sense of, ‘Is this good’? It’s more: ‘Why does this exist?’ I did a painting called Big Head. It’s just of a big head that looks like me with this sort of skinny, expressive body. Everyone really liked it. People kept telling me not to paint over it. But I couldn’t work in my studio while it was there. That’s when I realised I hated the painting – I didn’t like the body, the colours, the face – and it had to go. I painted over it completely. The moment I did, I started working on all the big paintings in my studio again.

AR You got rid of it even though people liked it.

TE That’s irrelevant. If I can’t live with it, I wouldn’t expect anyone else to. About seven years ago, I made a painting of myself that looked like decaying flesh. I knew immediately: this is me, I’m dead. It was brilliant, but I couldn’t live with it. I had to paint over it.

AR Because it was too accurate?

TE Because it was unbearable. And the other example is the cancer painting.

The Cancer Painting

AR Can you tell me about it?

TE During lockdown, in 2020, I went to the gynaecologist. I went in for one thing, and she found something else. She sent me for a scan immediately. I went back to my studio before driving to Margate. I opened a bottle of champagne – which tasted like sulphuric acid, by the way, that’s what drinking is like when you have bladder cancer – and I sat there staring at a painting I’d been working on. It was abstract. There was a bulbous, orangey-pink shape. And a really red shape. And then this sort of black, gnarly mass with a bit of yellow. I kept thinking, what is this? It looked finished, but I didn’t know what it was. Then my phone rang. It was the gynaecologist. She told me it was cancer. Two days later I saw a photograph of my bladder – and the painting I was looking at in my studio was almost identical to this photograph. If I hadn’t stared at the painting for so long, I might have come into the studio and just painted over it. But anyway, I kept it.

AR Would you show it?

TE No. Maybe one day. But it’s too close. I’m not going to stand at Tate Modern and say, look how clever I was, I painted my cancer subconsciously.

AR Earlier you were talking about how much less anger you carry now. For a long time, anger felt like such a visible force in how people understood your work – and how you were understood.

TE Yes, because with or without anger, with or without sadness or depression, I have always been an artist. That’s the constant. You can take the rage away – I’m still an artist. You can take the pain away – I’m still an artist. People have this romantic idea that suffering fuels creativity, but it’s not true. It’s just one condition among many. Van Gogh drank, took drugs. Munch was a complete opium-head, an alcoholic. Then he stopped and he was still a great artist. People who don’t know his biography wouldn’t even be able to tell the difference. The work doesn’t go when the chaos goes. People say, ‘I can’t concentrate unless I smoke’, or ‘I can’t work unless I’m miserable’. You can. You just don’t want to change. For me, the anger hasn’t vanished completely, but it doesn’t drive me. I don’t need it.

AR So what replaces it?

TE Presence. Focus.

Mad Love

AR There’s something else – a quality – that I hadn’t noticed before in your work. Can we talk about love?

TE When I had cancer, I fell madly in love. I never, ever thought that would happen to me again. But it did. And instead of going, ‘Oh, damn it, why did it happen? Why did I fall in love now, when it will all end?’, I thought, ‘Well, this is lucky. Right at the end, I fall in love. This is fantastic.’ That’s not tragic – that’s extraordinary. It gave me hope. And I realised something else as well: that often with love, I’ve been too greedy.

AR Greedy how?

TE Not selfish – but demanding. My life is very particular. I’ve lived alone for 23 years. I have OCD. I have routines. I’m an artist all the time – not sometimes. I don’t compromise easily. I need to think, I need to breathe, I need to have my own time, my own space: the way I live is how the work happens. But how the hell could I expect anyone else to bend themselves around that? So now I’m clear: I’m happy with my life as it is. If love can come into that and be happy in that situation, then that’s a bonus.

AR Are you still in love?

TE Yes. It’s never going to work, really, for lots of reasons. But it doesn’t matter, because I can still feel the butterflies.

AR That sounds like a different kind of freedom.

TE It is. It comes back to choice. I don’t want to suppress how I feel. I want to feel freely. And this relates to being an artist more broadly: true creative people pull energies through them and turn them into something that isn’t about destruction or greed. We’re not making war. I’m talking about the true potential of art to do good.

She Did It Anyway

AR And yet artists are often accused of excess – of ego, of indulgence.

TE That’s a misunderstanding of power. I use myself as my subject. Other people use me as a subject too. So I can’t be that boring. And it’s always been framed differently because I’m a woman. Twenty or 30 years ago, people had to come to terms with the fact that I was talking about big subjects, and just because they couldn’t relate to it didn’t mean I was just some screaming, moaning woman. I was actually saying that women are raped. Women are abused. Teenagers do have sex. Abortions happen. I was told it wasn’t allowed. But it was allowed – because I did it.

AR Do you feel there’s a difference between being understood and being recognised?

TE When I was younger, there were critics who were just horrific towards me, saying things that I don’t think they’d legally even be allowed to say now, and they got away with it. When I look back at myself in interviews or whatever – oh my God, no wonder they had it in for me – because I was just giving it back as well. And why shouldn’t I? They didn’t like the tone of my voice, they didn’t like my accent, they didn’t like how my mouth snarled up, you know – they just didn’t like the way I looked. Both understanding and recognition feel different now. Recognition used to feel hostile. Now it feels quieter. I think time has done a lot of the work. People don’t see me as a problem anymore. They see the work.

AR If you could speak to your younger self now, what would you say?

TE Keep going. Don’t stop. There were moments when I was so upset, so hurt, so broke – I nearly gave up. Being poor is brutal. Not having a choice is brutal. But even then, I had a pen and paper. You don’t need permission to make work. If you don’t have money, make it out of cardboard. If you don’t have a studio, use the kitchen table. If all you can do is sit in bed and write what you wish you were making – that’s still work.

AR Is it about dignity and choice?

TE Exactly. Poverty is shaming because it removes choice. The moment you reclaim choice – even a small one – you reclaim your dignity. There are systems set up to convince people they can’t do things, especially if they come from certain backgrounds. I was told ‘no’ over and over again. I just did it anyway. It took longer. It was harder. But I did it.

AR You’ve spoken before about grief – especially the loss of your mother – and how time reshapes it.

TE When someone loses their mother it’s not something you ‘get over’. You just learn how to carry it. When my mother died, I was on this sabbatical. I had space. That was a gift. Just like having cancer during lockdown was, in a strange way, a gift. I didn’t have to miss anything. I could sit with it.

AR Thinking of these experiences as a privilege rather than a burden feels quite radical.

TE It is. But it’s also practical. If you’re holding someone’s hand when they die, that’s better than being on a plane trying to get to them. These things matter. Perspective matters.

AR After everything you’ve experienced – illness, love, anger, recalibration – how do you think you and your work will change in the next decade, if you’re still here?

TE I don’t know. And I don’t need to know. The worst thing would be to decide in advance who I’m supposed to be. I’ve learned that if I stay present, the work tells me what it needs to be. I’m kinder to myself now. That doesn’t make the work smaller – it makes it more precise.

Tracey Emin: A Second Life is on view at Tate Modern, in partnership with Gucci, London, 27 February – 31 August. Crossing Into Darkness, a group exhibition curated by Emin, is at Carl Freedman Gallery, Margate, through 12 April

From the March 2026 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next When ‘Cancel Culture’ Came for the YBAs