The artist and art fair organiser – after contributing an artist project to the 2025 Power 100 issue – has a few things to say about how the artworld operates

How can you make the artworld the subject of an artwork? Since the late 2000s New York-based artist William Powhida has been satirising the workings of, and the experience of working in, the world of contemporary art. It made sense, therefore, for ArtReview to ask Powhida to contribute an artist’s project to this edition of the Power 100. Through the making of drawings, watercolours, diagrams and texts that frequently take aim at the institutions, personal networks and individuals – collectors, gallerists, curators, directors – that constitute the art system in his part of the world, Powhida reveals and ridicules the activity that otherwise lies obscure and unseen, but which makes the public-facing artworld appear the way it does to the rest of us.

Powhida’s approach is knowingly steeped in the tradition of institutional critique, though with a large side-serving of self-deprecating humour. ‘William’, his online biography points out drily, ‘has been advancing his own interests and attacking the art world for about a decade with marginal success.’ The success of Powhida’s satire, though, might lie in how the artist personalises the trouble of the artworld by highlighting the chasm between the artworld’s myth and its reality, the precarity of most artists and artworkers set against the privilege of a few: the pencil drawing How The New Museum Committed Suicide with Banality (2009) playfully sets out the ambivalences, compromises and conflicts of interest behind how art collector Dakis Joannou came to influence the decisions of New York’s New Museum. Meanwhile ‘THE TRUE ARTIST’, declares the meticulously rendered pencil drawing of a torn-out page of a notebook, with its obsessively bullet-pointed list, ‘WORKS FOR A TRUE FULL-TIME ARTIST YOU KNOW OF. / FILES LOSSES YEAR AFTER YEAR IN TERROR. / RENTS ANY LIVE +- WORKSPACE ANYWHERE…’

Compared to the often drier and more analytical lineage of institutional critique, Powhida’s work can be seen as a more personally invested – and riskier – form of artworld realism. His artworks remain objects to be viewed in the conventional gallery context – technically accomplished, smallscale, often unique and in traditional media – but speak unabashedly about the extremes of power and powerlessness in the culture and economy that surrounds them – still defined by elite privilege and concentrated wealth. And while an artwork speaking back to the gallery system is one approach to disturbing the system, Powhida has recently developed his critical provocation to possible ways in which the economics of art might be reorganised in favour of artists. This July saw the second iteration of the Zero Art Fair in New York, which Powhida cofounded with collaborator Jennifer Dalton; a fair where ‘all of the artwork is free, with strings attached’. Based on a novel legal contract and the observation that in reality artists ‘make a lot of work’ but that ‘the art market is built on a myth of scarcity’, Zero Art Fair allows collectors to take home artworks that they own after five years, while the artist retains a 50 percent share in the work’s first sale, and 10 percent resale royalty rights in perpetuity, a model geared to ‘enlarging the community of those who live with art and beginning a virtuous cycle of generosity’. Though it won’t abolish the art market as it currently exists, the fair makes the practical point that the rules by which the artworld operates are nowhere set in stone.

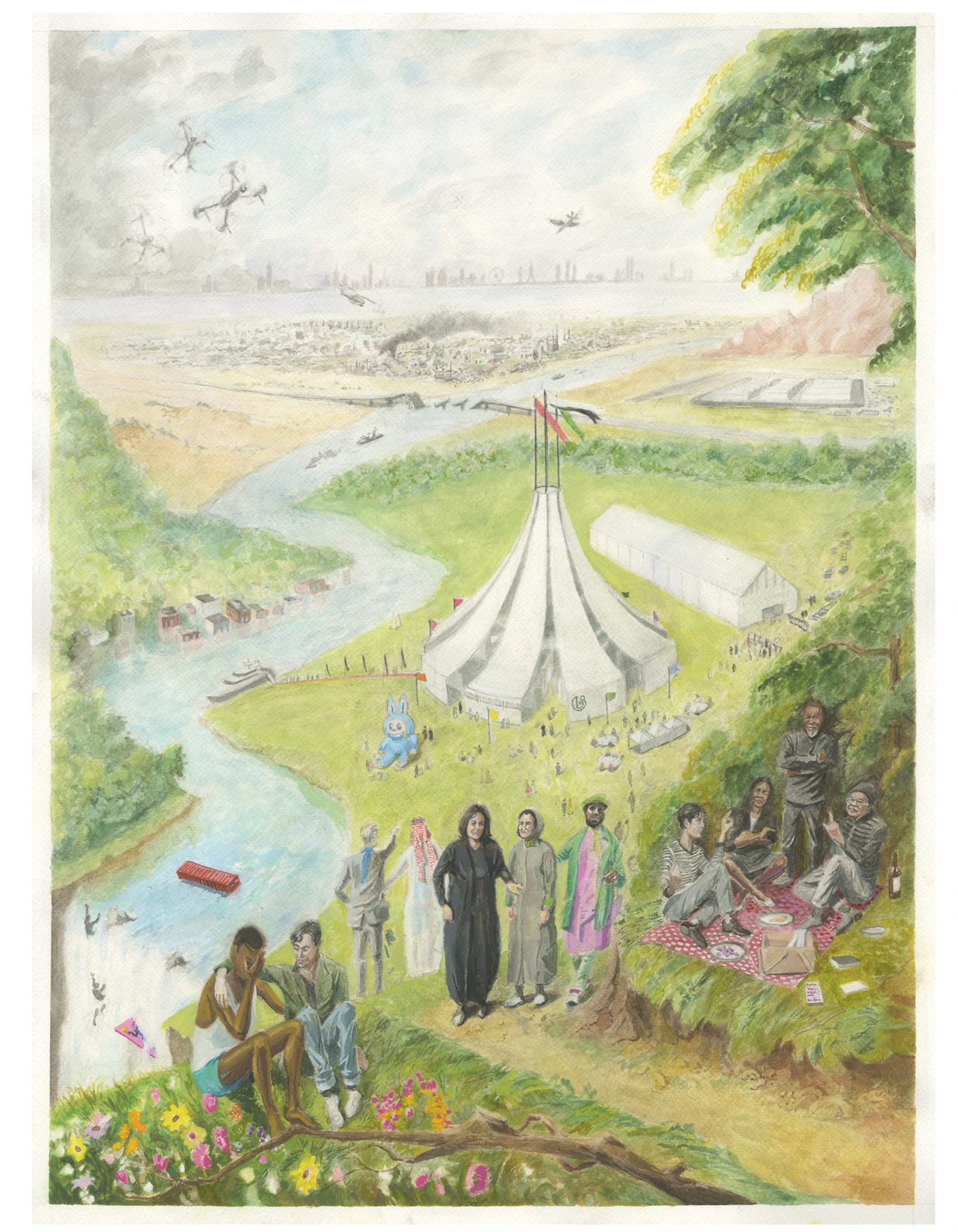

For the Power 100, Powhida turns his attention to the ‘categories’ of power to which each entry on the list is assigned. In the issue’s cover art, Powhida reflects on the geography and politics of power, and how this thing called the ‘artworld’ reacts to a moment marked by political change, conflict and instability.

ArtReview Tell us about what’s going on in the cover image you made for the Power 100 issue. We have this bucolic scene in the foreground and a dystopian scene on the horizon, but there’s something quite creepy about the picnic too.

William Powhida It started from a sense that there were interesting things happening in the artworld, but they felt very remote, certainly from my perspective here in New York. That whatever is going on in the artworld, it’s happening somewhere else in the world, and that it’s going to be happening in another place in another couple of weeks, or months. Which makes it interesting, but also inaccessible unless you have the time, the money, the leisure, to travel the globe looking for art.

So you have these artworld figures shown from this elevated perspective, situated at the top of this hill, looking down on maybe a biennial, or an art fair, which is cut off geographically by a river. Beyond the water could be a representation of Gaza, or just this idea that there are conflicts or events in the world happening, but which don’t seem to impact the experience of the artworld.

AR You’re in New York, a city that for much of the twentieth century was seen by many as the geographical heart of the artworld…

WP Going through the list made me feel like a regional artist in a decaying backwater. We have an interesting scene happening in, like, Tribeca. There’s still things happening, but I recognised the truth in that representation; that the most interesting stuff I’m not going to see unless I can jump on the plane to São Paulo or Sharjah.

I do think that New York has a degree of market and institutional power, but just in terms of where the gallerists are situated, what important exhibitions are considered or where the curators are residing, I don’t feel like they’re here in New York, and the discourse seems really limited here around art.

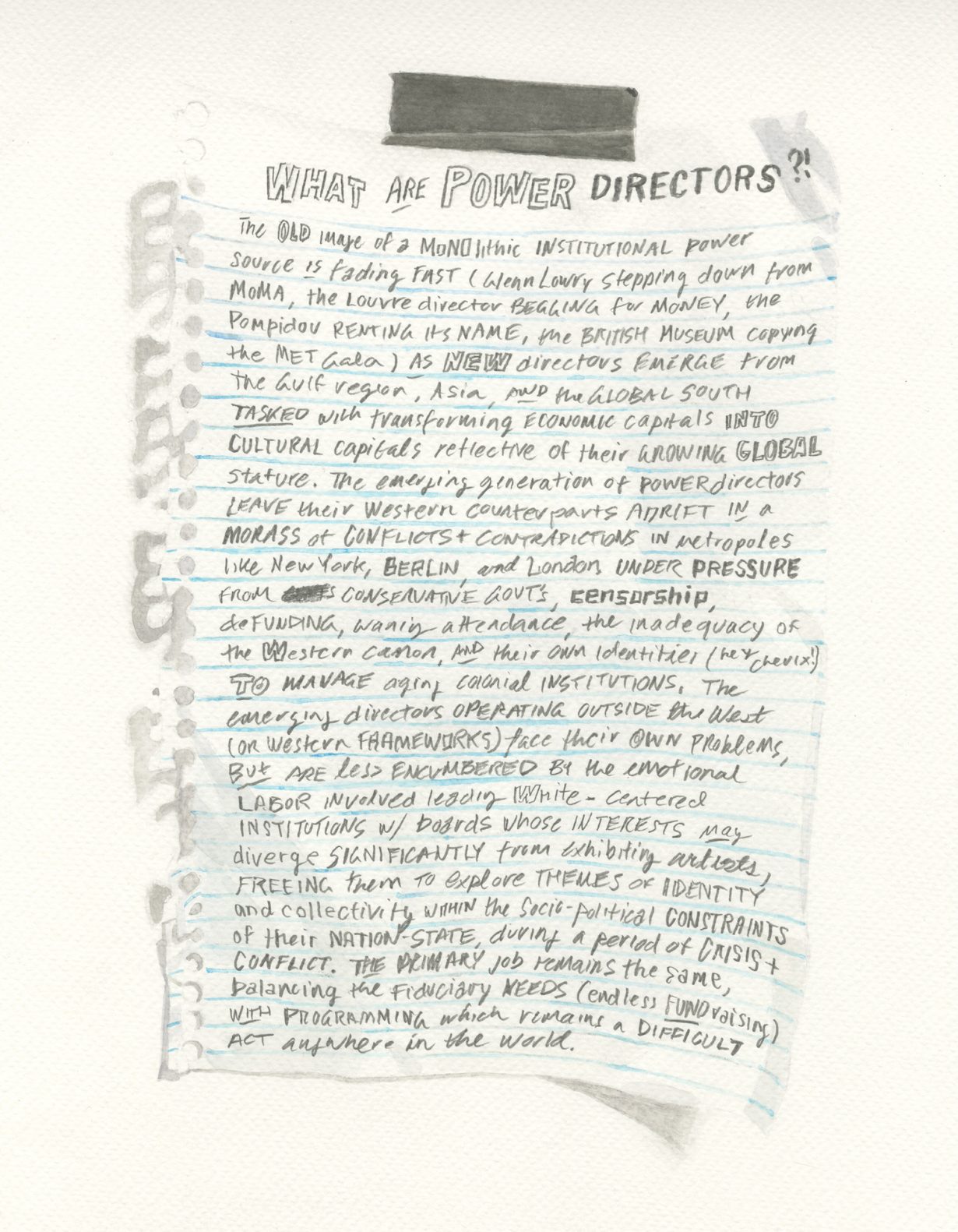

AR One of the other trends reflected in this year’s list is the different political uses of art at a state level, with some Gulf states using culture as a form of soft power, for better or worse – call it state making, call it art washing – while in the US President Trump is attacking art and culture, but presumably for equally strategic reasons.

WP I saw Amy Sherald featured pretty prominently on the list. On the one hand she’s emblematic of the use of art to uplift or represent previously marginalised groups, one of the positive things art can do (I think her practice is excellent), and the fact she is having all these big shows seems indicative of the success of that project. Yet at the same time, the material social-political conditions of her identity group and the identity group of many others is directly under attack, which suggests the project of cultural representation has not been commensurate or equal to what is actually going on, particularly in the US, but also the UK and elsewhere.

The ways in which different governments use art as a political tool feels indicative; I think you can read a lot into it. If a regime feels confident in its power and possesses enough wealth, it seems able to manage work that might be in contradiction to its purported values, or work that challenges the regime, whereas Trump clearly sees it as a threat. People have been debating whether the regime is authoritarian or fascist, but fascism sees art not as a right but a privilege that is subject to certain limits, and clearly that seems to reveal Trump’s very fascist tendencies. That said, soft power is about outward expression. If a state appears to privilege culture and they’re directing money to the arts, I will have a more favourable impression of them of course. But that makes it harder to contest or challenge the problems of wealth and capital accumulation, the flow of capital is left less contested.

AR Tell me about the Labubu on the cover.

WP Just a little nod to the fact that there has been a shift in the art market, and a lot of consternation about how to reach new collecting audiences, whether it’s a kind of generational thing – a generation of collectors who are less interested in contemporary art as we understand it and maybe more interested in collectibles and experiences. But also it’s an expression of that tension between what’s popular and what’s happening within biennials and triennials.

AR You’ve made a series of works that appear throughout the issue. They’re a continuation of the notebook drawings – realistic drawings of paper pages you’ve already handwritten – that you’ve been making for two decades. Can you tell me how you first came to make these?

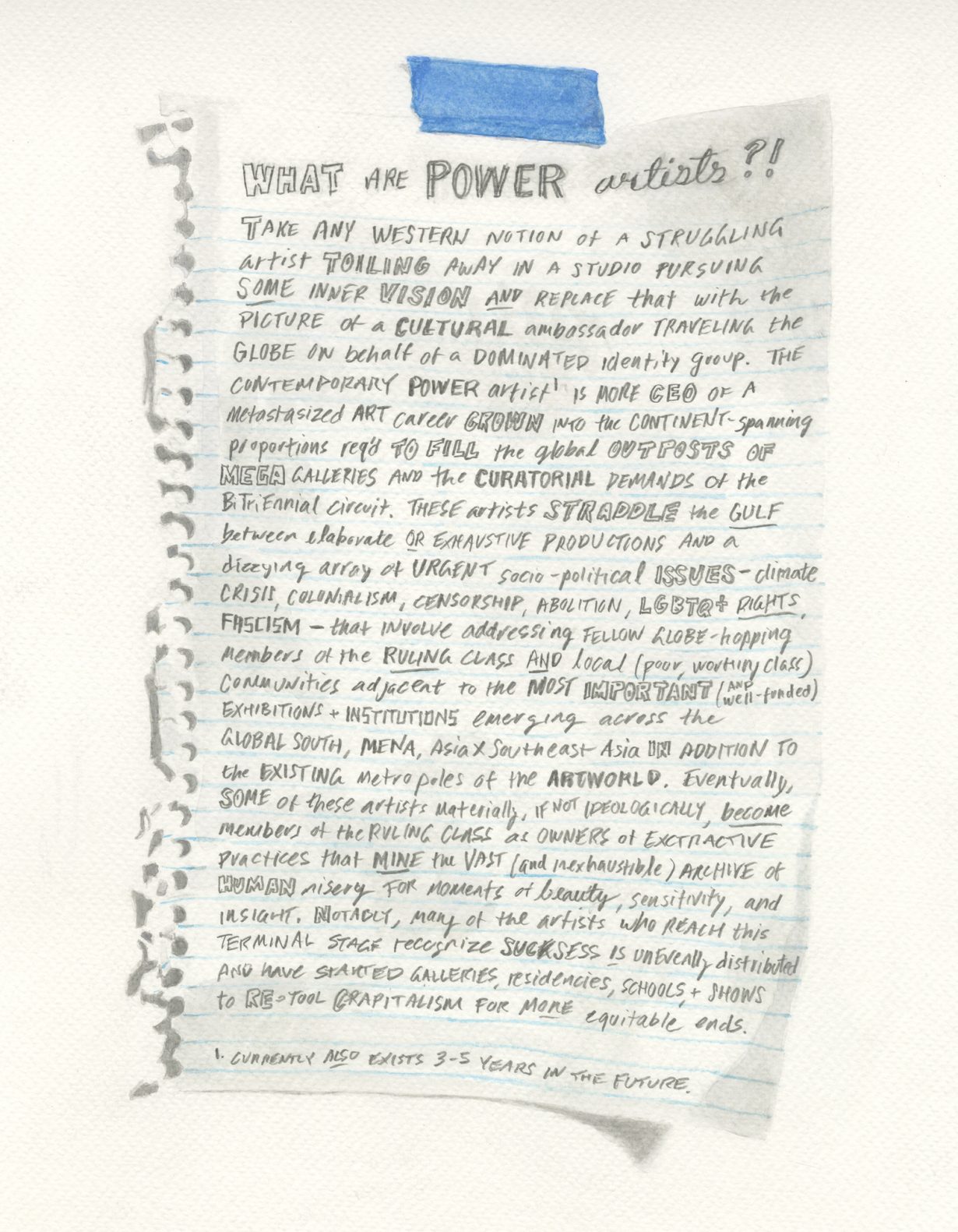

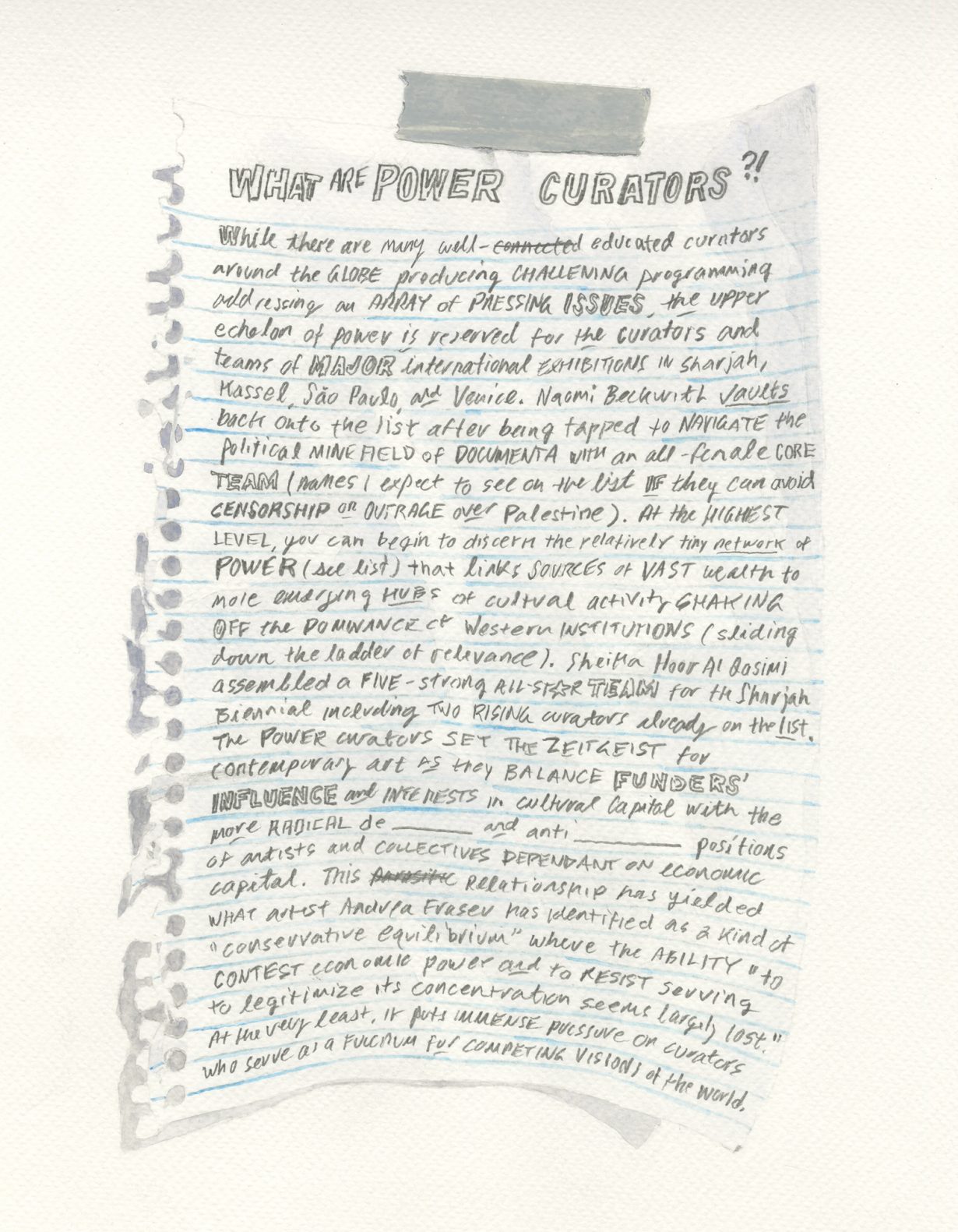

WP I was making art in my studio, and starting to write criticism for The Brooklyn Rail and a few other outlets, and I started to think about the difference between the public form of criticism that was released and the private conversations I was having; the things that I was thinking about, that didn’t make it into a published review, where I’m trying to be respectful of the artist, and their work, and people involved. The notebook seemed like a place where there was room for a little bit of fabulation, fiction, irony, a mode to share some of the private conversations I would have with artists and gallerists. For the works for the Power 100, I was interested in what each different group’s interests are and who they represent.

AR The conceit of the Power 100 is that it’s a hundred names, a hundred powerful individuals. But so much of your work highlights how individuals are caught up in the flows of capital, so who they might be might not be so relevant.

WP The artworld is reflective of the world: it flows out of the same systems and structures, and, yeah, flows of capital. I’ve been thinking about the diagram Andrea Fraser has in her essay ‘The Field of Contemporary Art’ [published in e-flux in 2024] in relation to this. In the diagram, it’s as if she threw five sheets of coloured Plexiglas down and assigned where they overlap as subfields, then assigned some poles of various types of power and varying access to different forms of capital. In that work it is types and groups that underpin this larger system and structure, but there’s no specifics. And then, looking at the Power 100, here are all these specific people at the institutions; where the institutions are located; what types of capital accumulations those nations or states have or don’t have; which forms of cultural capital they have. There’s also a process of delegation on the list that I recognise: one artist, one practice, starts to represent whole groups of people.

AR How cynical are you towards the artworld? I mean, if we only follow flows of capital, it suggests even the most powerful figures don’t have much agency.

WP I think we can agree that art is interesting. It’s not always good, it doesn’t always have good aims or anything, but art itself is the thing that I’m really interested in. Who gets to produce it? What are we producing? What are the ideas within that? I think this is where some of the problems arise in the way that art is used, or how it is positioned, and what claims are made about what it can and can’t do. This is where the power struggles occur, where it gets problematic or troubling.

Artists are engaging in those questions, the big social issues, but I wonder about the efficacy of that. On an institutional level there’s a sense that we have addressed and maybe resolved some of these problems only by elevating individual artists. Yet the very same conditions that they are making work about, legacies of colonialism for example, are still very active and present in the way in which those elevations are conducted.

It made me think of Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò and his idea of ‘elite capture’ and how the philanthropic impulse to change the world gets soaked up by more and more elite levels of people. I was thinking about how that idea could also extend to artists themselves. You know, there’s a certain point where if you get on the tracks of success – whether it’s a market-based track, or an institutional track, or a philanthropic track – the money that comes your way could be going directly to some dominated identity group, or somebody that really needs that money. But instead, it has to be processed through art and culture first. And at a certain point, the artists themselves are elevated to a level in which it is just impossible to imagine the level of money involved given the scope and scale of some of the practices. It’s like, ‘We can address these bigger social concerns, but we’re gonna have to do it through a limited number of artists and people, because if we change that, then we’d be talking about a different kind of social order.’

AR Making one First Nations artist famous is not solving a huge historical injustice.

WP Right, and there’s a huge difference between a land acknowledgement and an actual instance of handing land back. I think it is notable how many artists who reach a certain level of success feel an obligation to redistribute their own wealth into, for example, residencies or schools or building alternative infrastructure, which is really admirable, but also underlines the fact that a lot of the money and funding in the artworld goes to a few. And, you know, not every artist does something good like this!

AR I’m reminded of a drawing of yours, Political Artist (Mary Magdalene) [2019]. It is a heroic-feeling watercolour of a man, captioned ‘Political artist certain that this new, socially-oriented project in the desert 4 hours from LA will actually change the world’. The work is ambiguous, but I read it as not necessarily mocking the endeavour but mocking the ambition. You can try and escape, and trying is good, but kind of impossible, right? Artists tried in the 1960s, I guess…

WP It’s really, really fucking difficult. It’s just really hard to build those kind of utopian structures, so I think the impulse for a lot of artists or projects that I’m seeing now is instead, how do you retool, how do you redirect or redistribute things that are gained working within the system. I think to embed one’s practice in a local community or region, and step outside of the kind of global circuit, is really interesting, and I think it’s probably a healthier model for art that pushes back against some of the tendencies reflected in the cover illustration.

But if we’re talking about power and empowering your art – an artist who is embedded in a local community and working with people there who are outside of the institutional bubble still gets their legitimacy and currency through a shared global discourse. It is reflective of one of Andrea Fraser’s conclusions in her essay, which might be cynical to a degree, that all these different subfields within contemporary art have reached what she calls a conservative equilibrium in which there is still a mutual dependency that is hard to break or completely step outside of. So, while some of the most interesting artists and groups take money from the big pools of accumulation and find a way to get it somewhere else, becoming redistributive practices, they’re dependent on an existence within the system. If you were to completely step outside that flow of economic capital, that would make you invisible.

Explore the 2025 Power 100 list in full