“I very much wanted to highlight that we ignore the strangers – and smells, by nature, are strangers”

Smells are both evocative and nebulous. Embedded in each intake of air, they are at once irresistible (we must breathe, after all) and elusive (when they disperse, or mix with another smell, there’s no way to recapture them). The experience of smelling is equally volatile. Because of the anatomical ties between the olfactory bulb in the frontal lobe and the hippocampus in the limbic lobe, where memory and emotions are processed, smells readily evoke past feelings and nostalgia, easily transporting us back in space and time. And despite scents having a chemical basis, the perception of a scent does not completely depend on its molecular characteristics, but also its density (a flower’s aroma can become off-putting up close), purity (different smells can reinforce or inhibit each other), one’s own genetic disposition (eproctophilia, anyone?) and past experience (although personally I do like the smell of a dentist’s surgery). When a scent is being processed, all regions of our brain light up, making it impossible for scientists to get a stable, clean visual representation of olfactory perception. Smells are ultimately indefinite and always contaminated. There is no way we could understand the experience as clearly as we do with our visual or auditory senses.

Smells also carry a history, a history in which the olfactory sense is inscribed by cultural ideas and finetuned by ideologies. Academic Xuelei Huang’s new book, Scents of China (2023), delves into such a history of encounters – between chemicals and neurons, bodies and spaces, the self and the other, the East and the West – in which the sense of smell becomes a vessel to explore ideas of progress, hygiene, sexual attraction, sensory pleasures and revolutionary spirits. The flows of materials and people, as well as the propagation of ideologies, have all played a part in shaping a changing Chinese sensorium.

Huang’s book opens with a curious anecdote about a cesspool surrounded by a garden of Irish roses in northern China, planted by a Canadian missionary couple in the early twentieth century. The strange scene – conjuring both delight and repulsion – captured Huang’s attention. What follows is an inquiry into the history of smells that’s infused with ideas of contamination as well as modernity’s dualistic way of disentangling the fragrant and the foul. When her book was released last October, Huang sat down to talk about how smells can be a site of embodied experience and resistance.

Strange Smells

ArtReview How did you come to be interested in the olfactory world?

Xuelei Huang I wasn’t consciously thinking about smells until I read Alain Corbin’s book The Foul and the Fragrant [1986], which traces an olfactory modernity that emerged in eighteenth century France. Immediately I thought of some parallels in Chinese history and thought I could do something with this.

AR The idea of scents being a ‘stranger’ is central to your study. Could you expand on what this means?

XH I begin my book with the story of the cesspool, which is fascinating to me in multiple ways. On the one hand it is a metaphor of Western imperialism and its civilising mission, and the Irish roses represented that process to transform, to deodorise the environment – the ‘Chinese stench’ – according to their own ideas. But on the other hand, just imagine yourself entering a rose garden next to a cesspool – what would be your own olfactory perception? Would the air be foul or fragrant, or a little bit of both? It must have been a very strange mixture.

Of course, we do sometimes perceive things as fragrant or foul, but our odour perception is not a dualistic construction, and there are so many other smells that are in between. In Corbin’s book, he tells us how the modern project – the modern olfactory revolution – attempts to classify smells under the fragrant or the foul for all sorts of sociopolitical reasons. The cesspool-rose garden, however, challenged this kind of dualism. And that is exactly what I mean by ‘the stranger’. It’s a concept raised by sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, and refers to this indeterminate state between a friend and an enemy. According to Bauman, we can easily classify friends and enemies – that’s why we have so many wars, and there are ones ongoing, sadly; but strangers – those you can’t define – are very difficult to deal with for our modern institutions. If we can transform them into either friends or enemies, then that’s much easier.

For smells either defined as fragrant or as foul, the foul we deodorise, and the fragrant we promote, using politics, capitalism and other means. But I very much wanted to highlight that we ignore the strangers – and smells, by nature, are strangers.

AR You discussed this idea of the stranger in relation to a globalising olfactory modernity. What is olfactory modernity? How was China implicated in this process?

XH The olfactory modernity is one among many modernising projects in the nineteenth century. At its centre is the idea of deodorisation. For Europe, especially France and Britain, treatment of miasma became an issue of public sanitation at that time, and people sought to deodorise urban environments on a systematic, institutional level.

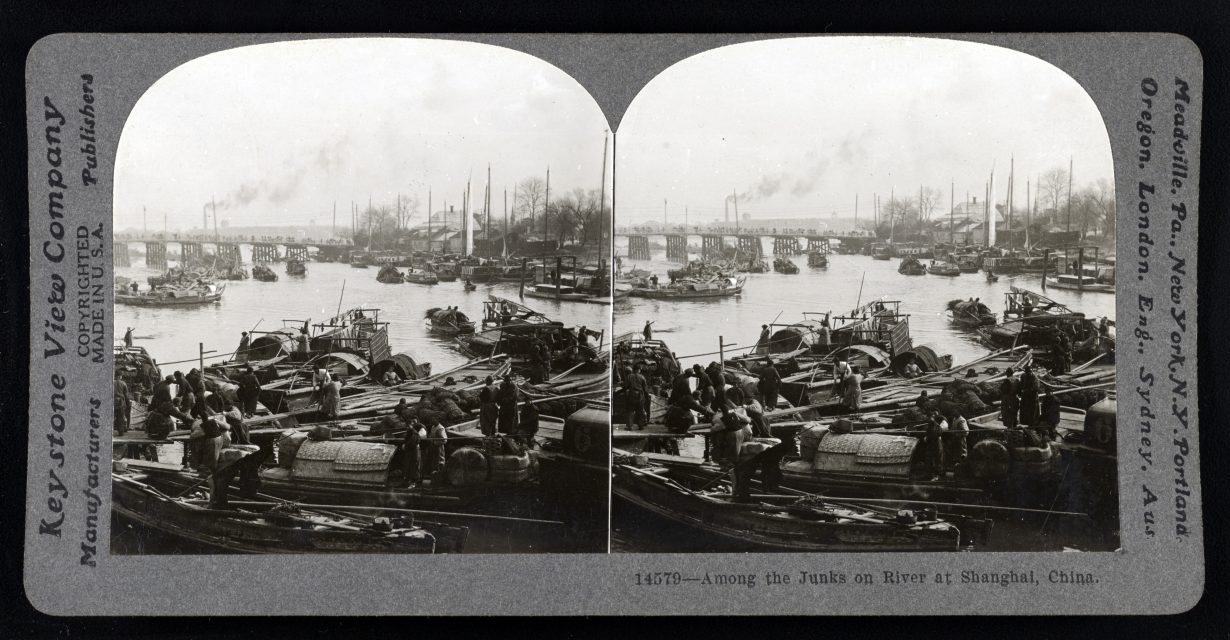

China also went through a modern olfactory revolution. In the mid-nineteenth century, when Shanghai and other treaty ports opened up to foreign trade, they were quickly industrialised, and as was the case with their European counterparts, the environment deteriorated. In my book, I investigated three projects related to deodorising Shanghai, in which they filled up ditches – commonly seen in the region’s dense water networks – and built a European-style underground drainage system, which is a key technology during Europe’s own sanitation campaigns. The system embodied the attempt to contain stench – as well as backwardness and the past – all beneath the surface and within those drainpipes.

But this narrative obscures two things. One is that the system that sought to contain stench destroyed the local ecosystem maintained through a natural cycle: night soils produced in the city would be transported to the countryside, where they were used to fertilise the land and produce crops. We tend to forget the fact that modern sanitation was actually disruptive in the first place. The second is that we can’t really contain stench: when the central area got deodorised, stench was dispersed to other parts of the city in an unequal way – it’s a stratified redistribution of smells.

AR Your book also argues that the sense of smell has mediated historical events. How is the experience of smell a social and historical phenomenon, even though we tend to think of olfactory perception as a personal experience?

XH Our olfactory perception is definitely a personal experience, but smell is also decided by many social, political and cultural factors, which we probably are not really aware of most of the time. This is related to the biological features of our olfactory system.

In my book I quote Ann-Sophie Barwich’s book Smellosophy [2020], in which she argues that our olfactory system is much messier than our other senses, like vision and hearing, because of the way our brain and the neural system work. In visual perception, we can identify objects more conclusively, but not so much for olfactory perception. In fact, how we identify things through smell is related to the process of memory and learning, which trains our olfactory neurons to recognise things in certain ways.

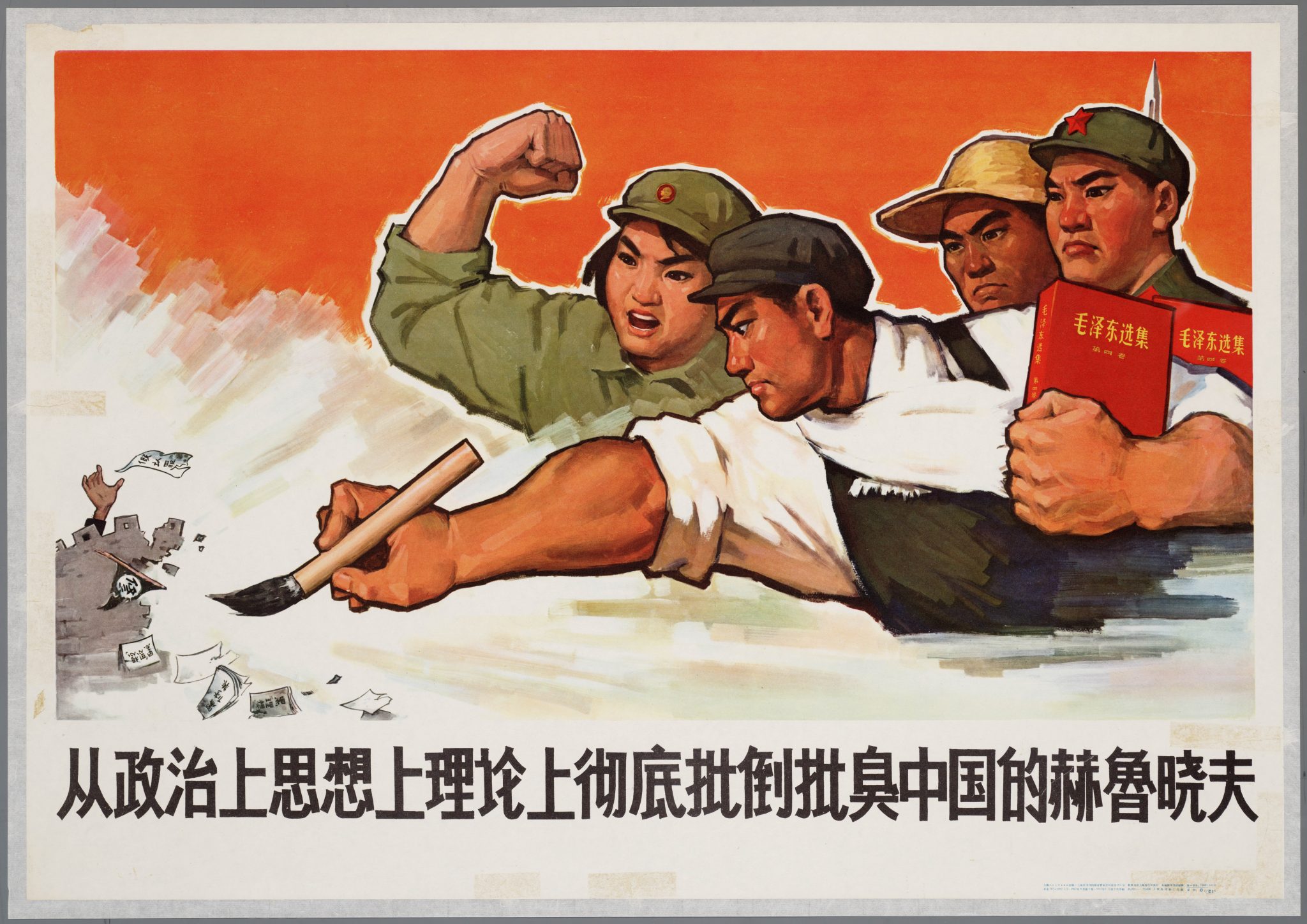

As a result, olfactory perception can be manipulated within sociopolitical contexts. For example, the moralisation of smell is quite common in many cultures – we tend to think of the fragrant as virtuous and the stinky as evil. The political use of smell is built on this concept. The project to deodorise Shanghai was linked to ideas of racial superiority, while the language of smell in Mao-era propaganda – like to ‘stinken / douchou [斗臭]’ class enemies or calling intellectuals ‘stinky number nine / chou laojiu [臭老九]’ – is an extreme example of how smells can be used as ideological tools. This is why I really would like to raise awareness about resistance.

High Culture and Refined Scents

AR In Western thought, the sense of smell is often regarded as a ‘lower sense’ in comparison to sight. Do you think this hierarchy of perception has shaped our experience of the world?

XH The Enlightenment thinkers and modernity certainly gave importance to vision because that represents the rational mind, and smell is a much more intuitive sense, which tends to be ignored or just taken for granted. And today, in the age of AI, the division between body and mind will perhaps increase further.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has inadvertently contributed to the public awareness of smell and its importance, because many of us might have experienced the loss of it. I lost mine completely when I caught COVID – it was such a weird experience, and the whole world felt so bland. Suddenly it makes us realise that we create a relation to the world through our nose. Smells accompany our breath, which makes them a connection between the internal and the external world, and by extension a bridge between our body and our mind. I think in our digital age it becomes more important to have this literacy in the language of smell.

AR In many cultures, there are traditions of wine tasting, kōdō or epicurean connoisseurship, in which the ability to detect olfactory nuance is a sign of culture and refinement – it seems like we do have a desire to pin smells down, even as they remain indeterminate and elusive.

XH That is very true. Although for Enlightenment philosophers like Immanuel Kant, aesthetics is vision-centred, and he famously claimed that the sense of smell can’t enter the shrine of aesthetics. He gave reasons why this is the case, but it is quite different from Eastern thinking and traditions. We have xiangdao or kōdō in Japanese [香道, the way of fragrance, in both Chinese and Japanese languages], and there’s a sophisticated perfume culture in China – as I’ve demonstrated in chapter one, where I use the Dream of the Red Chamber [a novel by Cao Xueqin, from the mid-eighteenth century, one of the four ‘great classics’ of Chinese literature] to show how smell is actually part of an aesthetic experience.

But with regard to these connoisseurial experiences, I don’t really think of them as a way to pin smells down. Rather, it’s more about appreciating olfactory richness and ambiguities, and experiencing them in deeper ways. That’s why we develop these rituals in xiangdao or chadao / sadō [茶道, the way of tea] – they help you appreciate the subtleties and nuances.

Towards a Contaminated Sensorium

AR Scents of China focuses on a history of scents, but throughout the book you also work with lots of materials from visual and literary culture. In what ways do you think visual culture, texts and the sense of smell interfere with – or contaminate – each other?

XH If historians could access an archive of smells, that’d certainly be great. But unfortunately we don’t have that. Some smell historians like William Tullett are actually calling for a more nose-on approach, but it’s not easy for humanities scholars, practically and methodologically – even if we do have this archive, or we do use our nose more, how to analyse the data is another question. Personally, I’m quite happy to be in the comfort zone of using written texts and visual sources to analyse smell. Because these materials can produce an imaginative dimension – words and images evoke smells, and also they indicate judgements. We don’t really have to have the actual smells to study how culture and society have shaped the sensescape.

As for how different senses contaminate each other, this is a great question. I immediately thought of Paris syndrome – the shock Japanese travellers experience when they visit Paris. Because normally in Japan – and same in China – Paris is very much idealised as a dreamlike place for romance, perfume and relishing life. But when they actually visit Paris and notice that the streets are not always fragrant, and not even as clean as those in Japan, many Japanese tourists are shocked and even traumatised.

This is how the actual smells of Paris contaminate the projected visual and textual imagery of the city. And that’s also why it’s so important to talk about embodied experience, because what we actually experience in a place are the invisible atmospheric sensations.

AR That’s fascinating. Visual culture definitely generates experiences outside our actual way of perception. In what ways can smells disrupt our reliance on our audiovisual senses?

XH This is where I think art can intervene. For example, Anicka Yi has done many experiments with odour that challenge some fixed ideas about gender and race [You Can Call Me F, 2015]. She also had a Turbine Hall commission two years ago at Tate Modern, but according to my experience, it didn’t seem to have been well presented because of the technical difficulties involved. The day I visited there were lots of visitors, which perhaps contaminated the smell she produced – but then maybe this was exactly the result she wanted to produce. And that is exactly why smell can’t really be prescribed; it is always fluid.

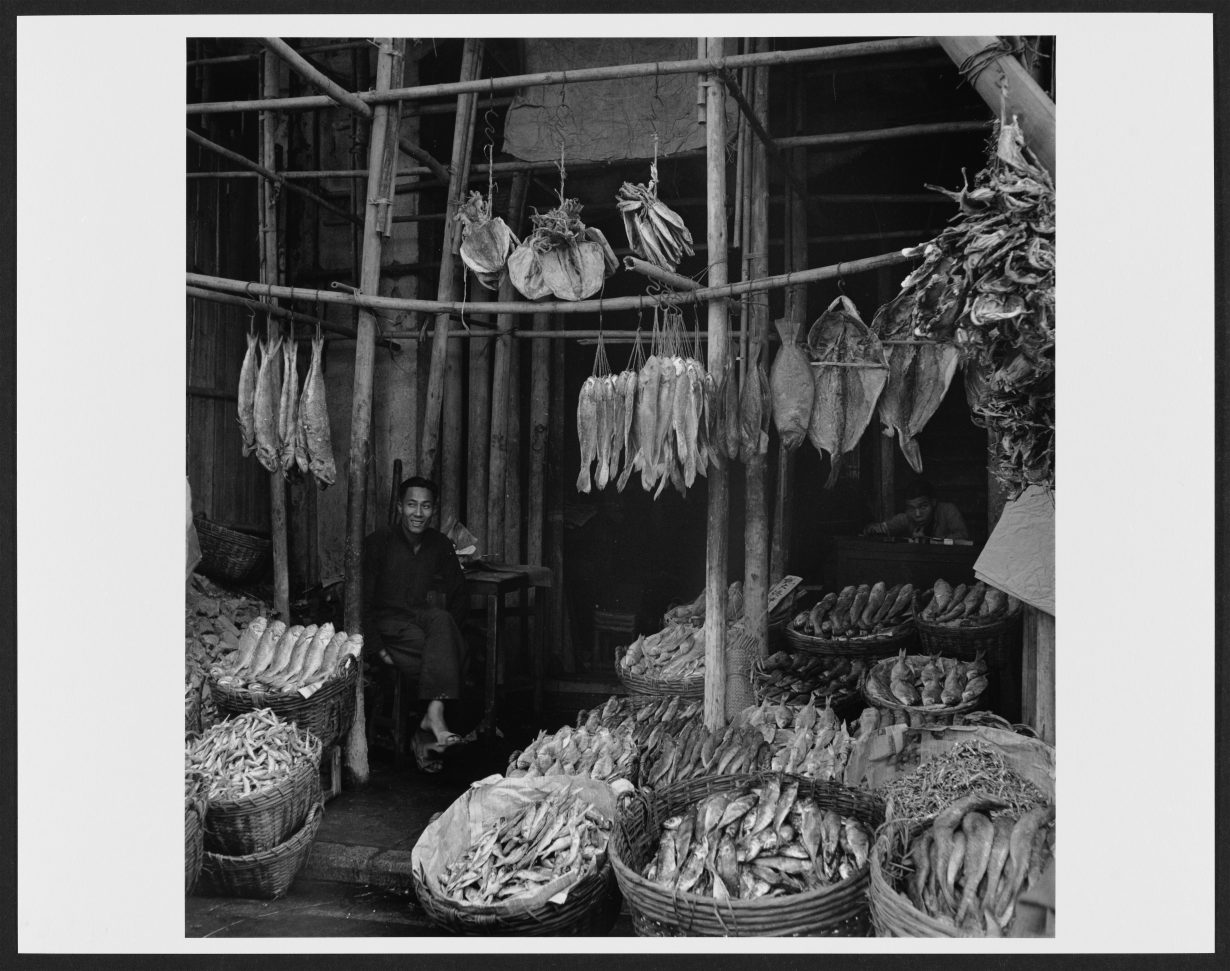

I’ve also been entertaining an idea of a performance project based on the colonial history of exhibiting humans at world fairs in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. I remember coming across the writing of a Western traveller in Shanghai, who remarked on the foul smells of the local soldiers but commented that they would be perfect subjects of display in London, were they to be properly bathed. And in an issue of The Illustrated London News, there were two Chinese boys who actually were exhibited in London, looking perfectly cleansed and groomed. So this is my idea for a provocative work of performance art – let’s say we have two Chinese artists who ‘display’ themselves in a Victorian salon setting, without removing the body odours from travelling in a boat or performing manual labour. In this sense smell can be used to provoke – and reveal what an ocularcentric history erases.

AR Do you like the smell of your book?

XH Let me smell it again… I do like the smell of books. It’s always nice to have a physical copy rather than an odourless e-book.

Scents of China: A Modern History of Smell is published by Cambridge University Press