“I have a very Oulipo way of working. I give myself a constraint, and then I have total freedom in the margins”

Born in Paris and raised in Tangier, Yto Barrada has, in two decades, gone from being a student of political science at the Sorbonne, as well as her family’s historian and archivist, to a prolific producer of photographs, prints, sculptures, films, artist books and para-institutional projects. Her solo exhibition at Pace in London, Bite the Hand, opens in March and comes on the heels of presentations at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Festival d’Automne in Paris and the Barbican in London. She simultaneously runs two nonprofits, both in Tangier: the arthouse theatre Cinémathèque de Tanger and The Mothership, a dye garden and artist residency.

I don’t recall when I was first introduced to Barrada’s work, but it was probably during a slide lecture – that’s how firmly canonised she already is. It might have been a lesson on postcolonialism, borders and migration, considering how she crystallises stories of transience and lost time at the boundaries of the Global North and South into poignant and surreal images seldom seen in history books.

Committed as Barrada is to building intentional communities and excavating minor histories, the ethos of her multilimbed practice comes as a necessary rejoinder to the kind of symbolic and hierarchical nation-building she’s critiqued, for instance, by photographing the Route de l’Unité (Unity Road), a volunteer-built public works project in Morocco’s Rif Mountains that sits empty despite its patriotic aplomb, and publishing the artist book A Guide to Trees for Governors and Gardeners (2014), a Swiftian account of Potemkin towns where elaborate cosmetic upgrades are carried out in advance of official visits.

These days at The Mothership, Barrada is cultivating a sanctuary for indigenous plants that are vanishing amid Tangier’s urban development. Her care for the natural world spills over into her roles as a champion and curator of late artists and thinkers, including Luis Barragán, Fernand Deligny and Bettina Grossman. When making space for the stories, wisdom and learning of her living collaborators, Barrada is like an Oulipo poet: constantly setting up what she calls constraints – I call them structures of support – for freedom in play and education to coalesce.

A Witch Practice

ArtReview What’s been on your mind, Yto?

Yto Barrada I have all these temporalities that are sometimes wrestling with each other – the demands of deadlines, family responsibilities and the two nonprofits I work for – and I’m terribly slow. When there’s an important deadline, it’s my contradictory nature to be very productive on something off-centre, to go into deep research on something peripheral. Nowadays I produce by walking. No pen, no computer. That’s one of my forms of resistance.

AR Your work dwells in the poetry of the peripheral, both in the sense of a fine detail won from the rabbit holes of research and in the sense of geopolitical centres and margins.

YB Back home in Tangier, civilisation means what would be considered here in New York ‘losing time’. Talking to strangers, inquiring about the health of elders. Activities that are central to life in a community.

AR They seem to inform the feminist ethos of The Mothership.

YB The Mothership is an extension of my home and my practice. It’s a farmhouse centred around a dye garden. Gardening is also a way of being indulgent with time and with results. You learn that you don’t have a lot of power because there are droughts, cycles, soil that’s different from one year to another, seeds and plants that behave differently when you move them, decay. I wrote a little note for you –

[Yto goes to the back of her studio and returns with a green Post-it. The note reads, ‘L’inadéquation.’]

‘Inadequate.’ It’s the time of plants and the time of education. When you plant a garden, you want it to bloom during workshops and colour walks, you want the bright yellows to grow in the right place at the right volume, but of course nothing goes exactly the way you want. We’ve learned to adapt. Many of the indigenous plants that I’ve reintroduced to the dye garden take four or five years before I can get the roots out. The roots are what yield colours.

AR Tell me more about the process. Do you always extract dye from the roots?

YB Sometimes you make colour with the roots, sometimes the bark, sometimes the leaf. From dyes you make pigments, and from pigments you make paint. It’s a continuous process where everything is reused, and everything has a function.

AR Where does a novice begin?

YB When you start as a dyer, you forage. It’s a haptic experience. In the beginning I had this book with different recipes, and I went home to Tangier, where I have a friend who’s a botanist, and I gave him the book and said, “Tell me where I can buy these plants.” Then he toured my garden, and he said, “You already have seventy-five percent of them.” That’s how the responsibility of cultivating the dye garden came about. The gallerist Seth Siegelaub wrote beautifully about textile being this construction at the crossroads of the history of labour and the history of architecture. He saw in textiles the beauty of those intersections.

AR And you see dyes that way as well?

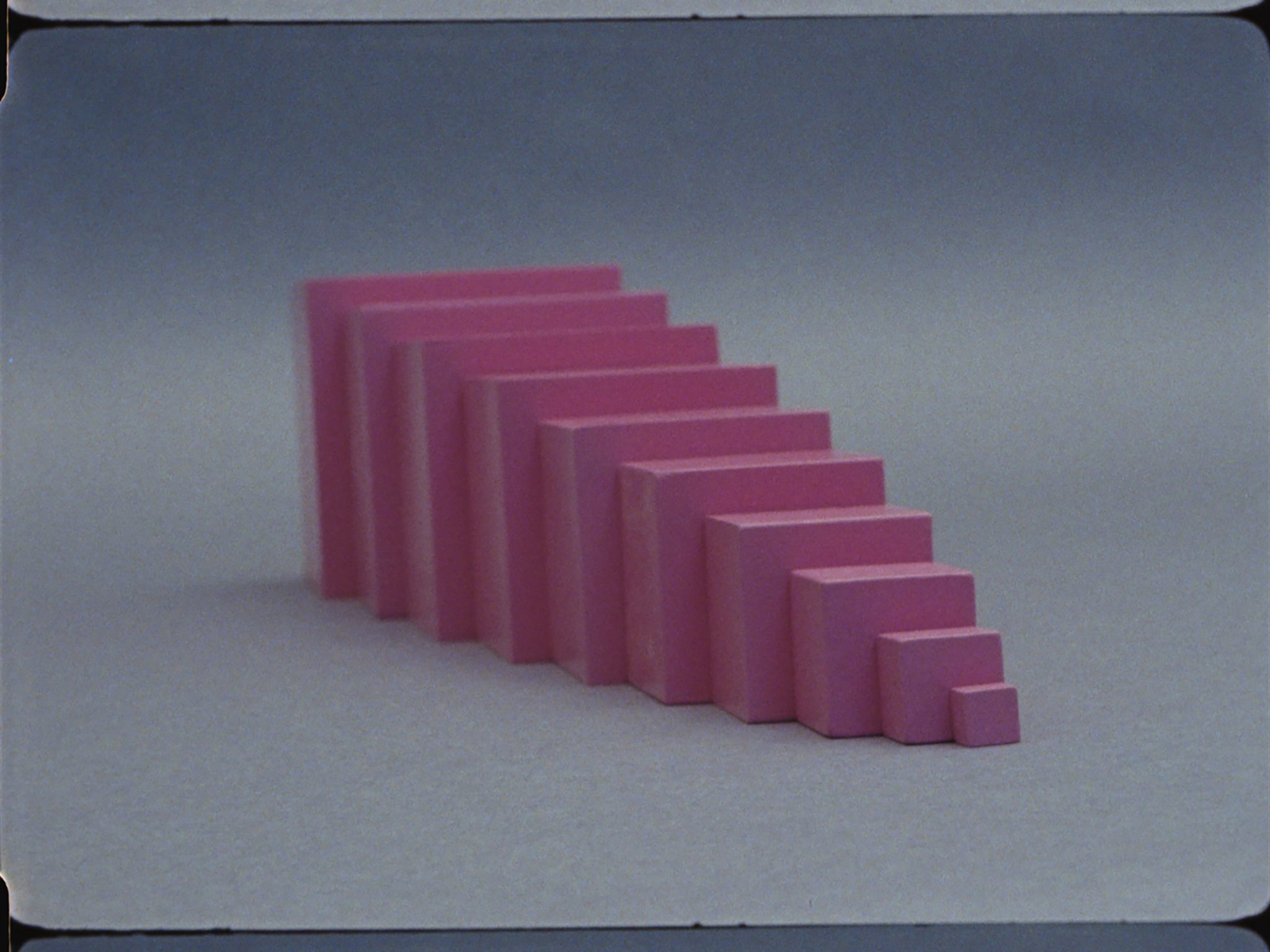

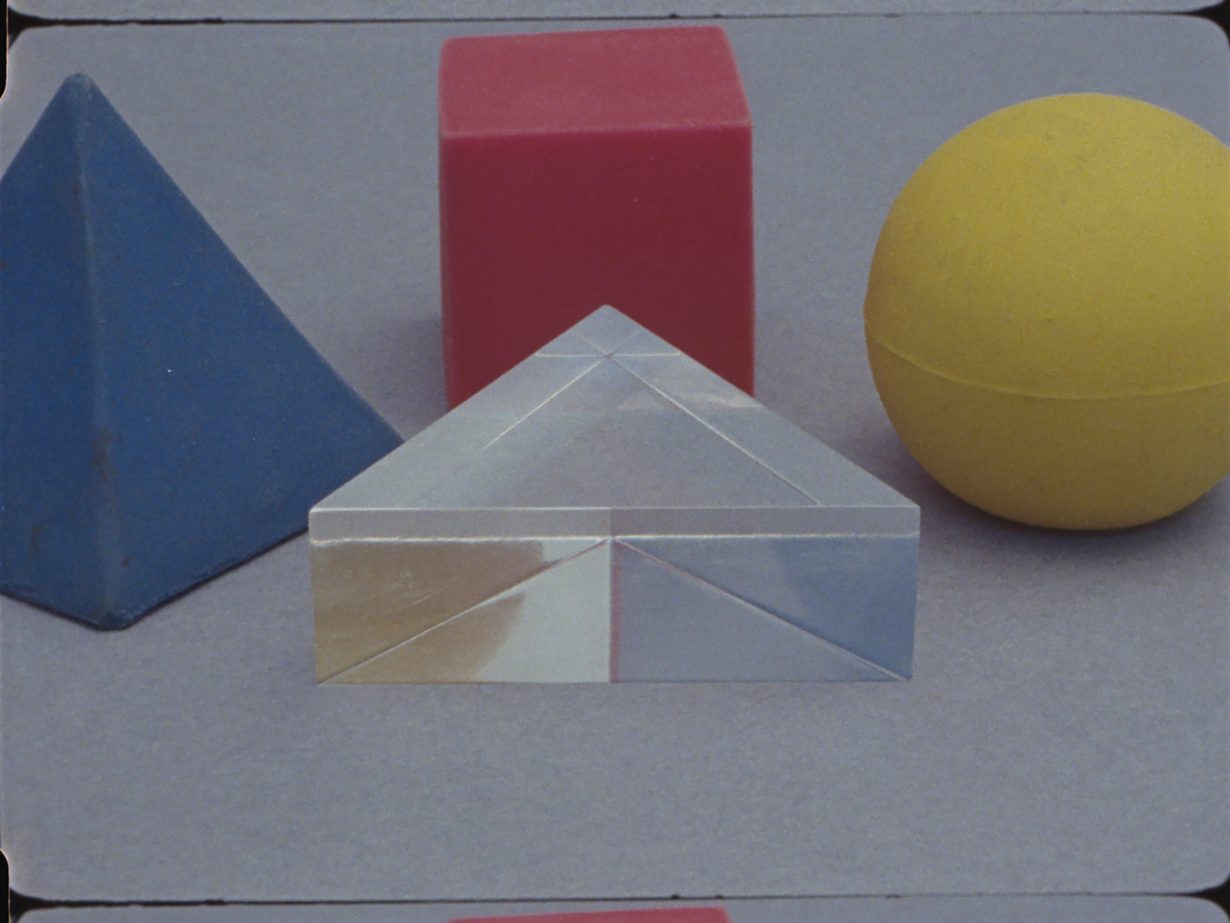

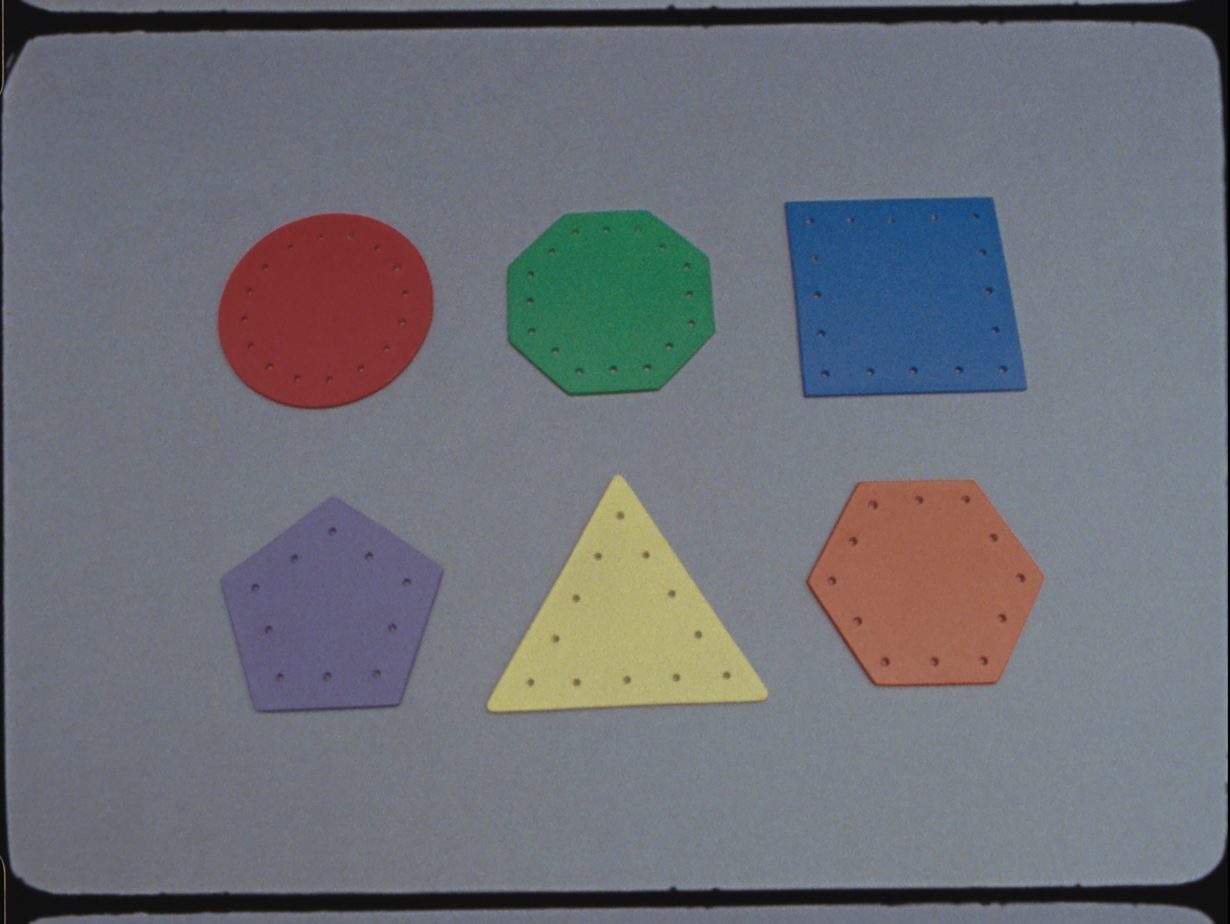

YB Dyeing is like a witch practice of learning recipes, discovering old recipes that are lost and asking people to teach you what they know. I collect educational materials. Some of my books are samplers, notebooks from weavers, Japanese books and schoolgirl embroidery books.

Authoring the Accidental

AR Do people gift you books when they hear you’re researching something?

YB No, I get them from the streets, bookshops, everywhere. I’m a big junk person. I’ll pick up anything. Especially in Brooklyn, the streets are wonderful. And books are a great form for both space and time.

AR They immerse you in a different temporality.

YB The making of them also allows for a different kind of sequencing. It allows for less efficiency. You have books, but you also have people with oral knowledge. In Morocco there are isolated communities still using dyes. They use them in cosmetics, or they dye their hair with pomegranate skin.

AR Oral history and storytelling are important to your work. In your film Tree Identification for Beginners [2017], for instance, you narrate your mother’s memories of visiting America with Operation Crossroads Africa. For that film, you corroborated her memories with state papers and then turned the official records back into a voiceover. Do you ever find oral stories unreliable?

YB The way I remember things, the unreliable narratives, are part of oral history. There’s a great book called The Art of Memory by Frances Yates about how epic stories were remembered. The theory is that it’s a construction, like a building, and each story is a different room, so you have to picture it as an incredible architecture. Each story in the epic was placed in a different room.

AR Is your photography a form of archiving?

YB When you print a photograph, the techniques you employ to supposedly make it last a hundred years are full of vanity. Though I think about the durability of colours, and that led me to my film A Day is Not a Day [2022]. It’s about facilities in Florida and Arizona that accelerate the weathering process of colours.

AR How did you hear about these facilities?

YB I was in a natural-dye workshop in Paris with a textile conservator. She said she’d tested her recipe with a Xenotest, where they can show you what 20 years of fading looks like in an hour. I called a facility, and we looked at the budget, and at $3 an hour [of ageing] it was something like $7,000 [for 20 years]. But the person who ran the facility said, “You can film it.” Years later, in 16mm, I filmed a weather-accelerating machine.

AR How do you decide which images to include in your work?

YB Some images just stick. I think it takes working on other things meanwhile, paying attention to chance. One of the two printers at The Arm, a letterpress shop in Brooklyn that I work with, said, “Authoring the accidental, that’s what we do.” One of my schools of thought comes from the experimental group in Paris called Oulipo. For me, they are the big masters, so I have a very Oulipo way of working. I give myself a constraint, and then I have total freedom in the margins.

A Learning Archive

AR The Strait of Gibraltar is visible from The Mothership’s dye garden. The strait was the subject of your first major photographic series, A Life Full of Holes [1998–2004]. Location-wise, your work seems to have come full circle. Meanwhile, so much of the world has changed.

YB With climate change and with Tangier’s coast being developed, my place has turned into a sanctuary. The plants and trees that are disappearing all around us are preserved there.

AR You run an artist residency there as well.

YB We had residents come last spring and summer, and now we’re preparing for the next season. We’re building a botanical archive, a learning archive. We print phytograms, we print on film with plants, and now we have a printing press at the Cinémathèque de Tanger, the independent cinema I cofounded in 2006. A Risograph machine. So we’re starting some publications. We also study seed preservation. [Artist] Vivien Sansour has been doing that. So has Jumana Manna, who had a show recently at [MoMA] PS1.

AR Right, Sansour founded the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library, and Manna’s show at PS1 included her film t [2018], about ICARDA’s gene bank, and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

YB In Morocco there are also artists interested in the fishing trade, monsters in the Strait of Gibraltar and land sovereignty. Our first resident, Noureddine Ezarraf, was working on what he called a form of Berber futurism. He made dyes with madder and pomegranate skin, and he started making his own crayons with a meat grinder. Last summer we had [Parliament-Funkadelic’s] George Clinton come for his eighty-second birthday. During COVID he’d started painting. I discovered he was colourblind, so I made some paint for him with madder and insects from the garden. He worked hard and painted late into the night.

AR You’re there in the summertime?

YB I’m there every two months. My parents live right next door, and the garden needs me.

Bite the Hand, a solo exhibition of work by Yto Barrada, is on view at Pace London, 22 March – 11 May; Barrada’s outdoor sculpture installation Le Grand Soir opens at MoMA PS1, New York, on 25 April

Jenny Wu is a writer and educator based in New York