In the lead up to the opening of Thailand Biennale in Phuket at the end of the month, Hera Chan reflects on the image of the postcard-perfect island

Any self-respecting guide to Phuket would describe a timeless tropical island moored in an aesthetics of hospitality: magnificent beaches, historic town centres, dynamic cultural activities and bustling nightlife. As the roving Thailand Biennale, this year titled Eternal [Kalpa], grounds itself around the island, different experiences of time are explored via life cycles: from that of the coral in the sea and the agricultural routines on land that are governed by the lunar rhythm, to vestiges of a plantation economy in the island’s north, to the metaphorical ‘rubber time’ of the tropics, which gives elasticity to history, as much as it stretches meetings and deadlines.

The name Phuket itself is a misspelling of ‘bukit’ or ‘hill’ in the Malay language. Phuket itself, founded as an official settlement town and industrial tin-mining hub in 1827, is situated in the Andaman Sea and part of the larger Malay region. In Western colonial sources and derived from the Portuguese, Phuket used to be called Junkceylon, which came from the Malay term Ujong Salang, which in turn came from Thalang, the Indigenous name for the island. In the European colonial era – though Thailand was never colonised – ships would stop off in the former centre of Thalang province to refuel. Whispers of former piracy, police officers with magical powers and bloodlust can still be gleaned from the stories told by locals. The spiritual power of Phuket includes shrines featuring deities such as Toh Tahmi to Toh Sae (‘Toh’ means ‘imam’) who guided former Fujianese miners toiling in the tin mines. Though the mines have been defunct since the 1980s, the shrines remain centres of spiritual activity today, and play host to the annual Vegetarian Festival, in which a nine-day cleansing ritual with daily processions is led by spirit mediums. Purportedly, there are around 2,000 spirit mediums who live on the island, spending the rest of the year working regular jobs. These forces have become part of the governing logic of the Biennale itself, wherein artists such as Andrew Thomas Huang, Riar Rizaldi, Saroot Supasuthivech and Taiki Sakpisit engage these unseen entities in their works.

The Thailand Biennale was initiated in 2018 by the Office of Contemporary Art and Culture in Thailand and took place in Krabi, Korat and Chiang Rai respectively, before finding its latest temporary home in Phuket. The decentralisation of the Biennale is a key part of its remit, acknowledging the multiple Thailands that exist and persist outside the capital. When the curatorial team – artistic directors Arin Rungjang and David Teh, and curators Marisa Phandharakrajadej and myself – gathered in Phuket for the first time at the end of August 2024, we were ushered to a TV-special-ready press conference with emcees and notable local stakeholders dressed in Peranakan garb. Earlier that year, season three of The White Lotus was filmed at multiple sites on the island in addition to Koh Samui. Delving deeper into and through the supposed glamour of this tropical getaway, the project of Eternal [Kalpa] is to reinsert Phuket into larger worlds, both in the present and historically.

The exhibition is being constructed through and with the people we have met in Phuket –including marine scientists, surf champions, café owners, anthropologists, hospitality experts, community historians, mining-family descendants – who are well versed in the vernacular of tourism. For example, for Zheng Mahler’s video installation Seagrass Kra Chang (2025), the artists worked extensively with the Phuket Marine Biological Center to create protected areas for the growth of sea grass – the main food source of dugongs. Several dugongs – more similar genetically to elephants, the latter a national symbol of Thailand, than to other marine mammals – have returned to Phuket, while the profitability of tourism and the related need to protect the beaches has resulted in sea-based extraction industries moving elsewhere. In unifying the vernacular of everyday life on the island and the aesthetics of tourism, the curatorial team issued invitations to artists who are keen explorers and listeners. At what point can Phuket’s story be the story of a visitor? When do you feel you can speak to the history of a place from which you don’t originate? Our prolonged field trips to the island have led us to question the idea of an ‘extended stay’ and the meaning of rooting a largescale exhibition project in its locale.

Naturally, when we began this project, I too imagined the tourist-postcard, beach-nomad work situation. What quickly became apparent were the other ways in which that seductive image of the sun-blessed resort island was operating and being operated in Phuket. As a collaborative project, Eternal [Kalpa] is itself a decentralising gesture, inviting reflections and refractions of the island. The image of Phuket as a White Lotus luxury-style tropical paradise is self-inflicted by marshals of the tourist economy who in a recent past-life ran the industrial extraction of island’s tin, tantalum, rubber and coconuts. What draws people to Phuket – tourists and others, ourselves included – is its economic intensity, centred on services and experiences including turning-down beds and recommending authentic road-side food stalls, appraising and reselling gold, hustling people into nightclubs, sex work, the blue economy of marine environments, and even culture work in the contemporary art industry.

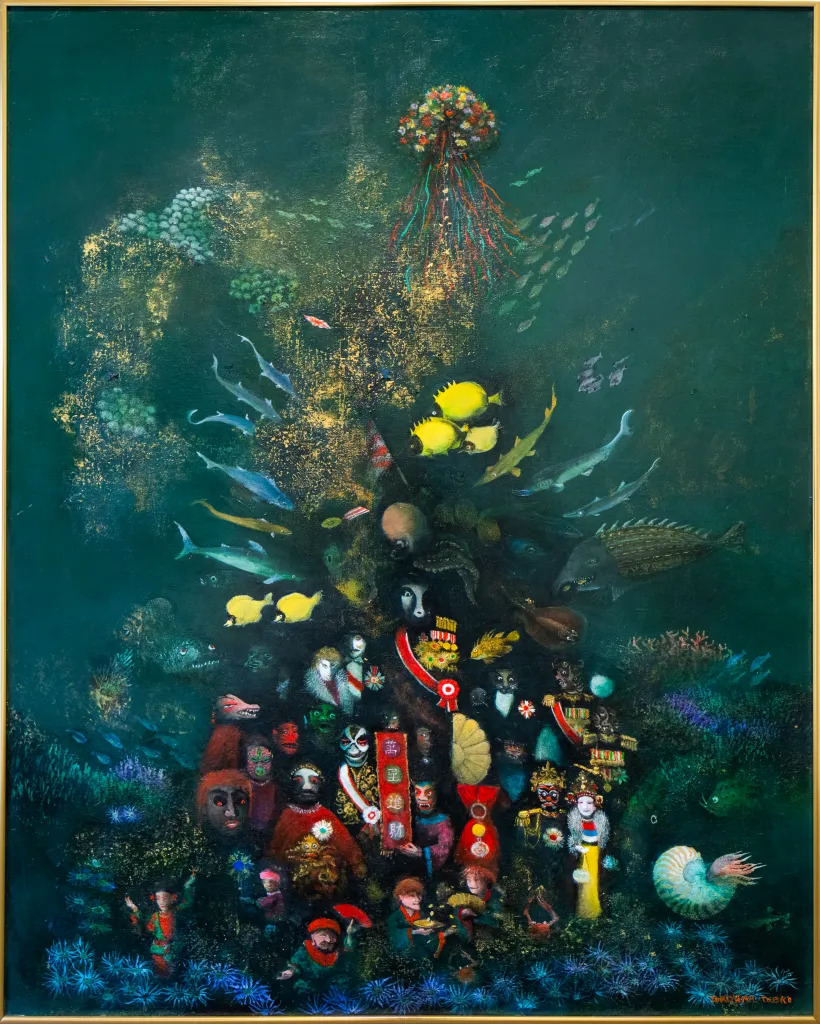

In her essay ‘You only think I love you long time’ (Arts of the Working Class, 21 June 2022), filmmaker and social anthropologist Rosalia Namsai Engchuan details the construction of gendered Thai tourism in the wake of the Cold War and the female stereotype of ‘The Thai Beauty’ in foreign advertising. Engchuan describes an ‘operational image’ that casts the so-called Thai beauty as submissive and inviting. In Bangkok in 1991, Japanese artist Taeko Tomiyama staged a two-person exhibition of paintings and prints with Jarassri Roopkumdee titled Let’s Go to Japan! The Thai Girl Who Never Came Home, in which Tomiyama surrealistically depicted the journey of Thai female migrant workers who found their way to Japan. Continuing this thinking of affective economies and emotional labour, artists such as Ariane Sutthavong, Imhathai Suwatthanasilp, Oat Montien, Pauline Curnier Jardin & Feel Good Cooperative, and Wilawan Wiangthong have engaged in collaborations with Phuketian performers and purveyors of love in newly commissioned artworks.

Ultimately, what brings over eight million annual visitors to Phuket is tourism, while the remaining population is comprised of local residents including born and bred Phuketians as well as those who have moved there to work. Erstwhile, TOQA, an artist and fashion label from Manila, is collaborating with Ying Batik, a bespoke clothing and textile producer headed by the artist Ying who paints using traditional batik techniques, to design workers’ uniforms handpainted with coral motifs for the invigilators of the Biennale, the result looks like something made for both labour and leisure. Throughout the multitude of name changes that Phuket has undergone, its possibility of regeneration seems to know no bounds.

ArtReview is partnering with Asymmetry to publish a series of cultural reflections by the foundation’s fellows