A new survey of the group’s work and the injustices they faced offers a bittersweet viewing experience tinged with both pride and sadness

‘Send this one back to the people [and] let the people demand an answer!’ Each of the 13 handwritten messages in Keith Piper’s 13 Dead (1981) concludes this way. Written on the back of postcards, each is dedicated to one of the young people, aged between thirteen and twenty-two, who died in London’s 1981 New Cross Fire, in which a house hosting a birthday celebration went up in flames, killing several Black and mixed-race partygoers. These deaths, initially thought to be caused by an act of racially motivated arson, spurred the local Black community to organise a ‘Black People’s Day of Action’, which saw 20,000 people march through London to protest the tragedy. The collection of postcards is set against a panel with charred and peeling wallpaper, bordered at the bottom with a skirting board. The work is both a remnant of the past and, with its instructions to seek justice, a manual for the future.

The more things change… reexamines the work, both artistic and political, of the Blk Art Group, a group of young Black art students from the Midlands who fought for institutional representation while questioning and critiquing the social and political landscape of Britain. Showing these works in Wolverhampton is a homecoming of sorts, given that the group held their first show, Black Art an’ Done, at the gallery in 1981. Across three gallery spaces, the exhibition focuses on work made by Claudette Johnson, Marlene Smith, Keith Piper and Donald Rodney during the group’s active period, between 1979 and 1984. Later works by the artists, including pieces from Janet Vernon’s more recent jewellery and textile practice, are interspersed throughout, along with new commissions from Johnson and Smith.

Archival materials displayed in the first gallery provide new context to the Blk Art Group’s work. These include correspondence between the group and museum officials regarding the development of exhibitions such as The Pan-Afrikan Connection, held at London’s Africa Centre in 1982. The conversations over shows that laid the foundations of the highly influential British black arts movement reveal the group’s grit, persistence and strategic approach to getting their voices heard on their own terms. Reading these letters is a bittersweet experience; anger at the injustice these artists faced mixes with pride in their successes in opening doors for artists of colour working today.

This ambivalent sentiment permeates the rest of the show. Johnson’s Trilogy (1982), a triptych of slightly larger-than-life full-body paintings, depicts lone Black women standing tall and taking up space. In Trilogy (Part Three) Woman in Red, the woman stares defiantly at the viewer with her arms akimbo, grazing the borders of a canvas that only just contains her. One of the vitrines displays a promotional text for The Pan-Afrikan Connection that includes Johnson’s artist statement: ‘My work is about […] the experience of the African woman born and raised in the West. It attempts to express the myriad aspects of oppression, racist and sexist, that have shaped us. It deals not with specific events but with our responses: anger, frustration, fear and depression.’

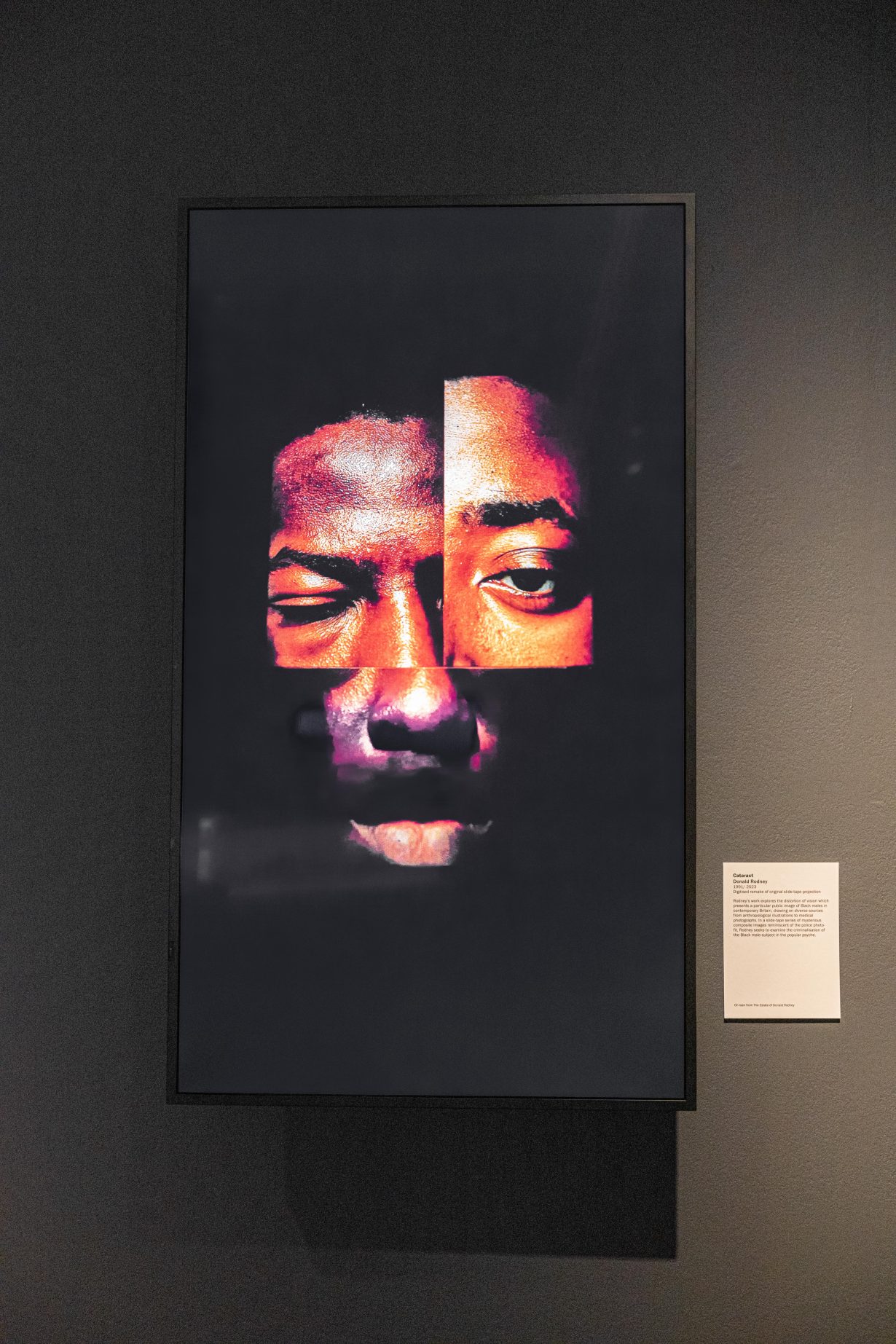

Owen de Visser. © The Estate of Donald Rodney

Johnson’s focus on and understanding of the condition of the Black Western woman is as relevant now as it was 40 years earlier. This same is true of the other artists’ work. Rodney’s Cataract (1991/2023), which features collaged portraits of Black men, alludes to the monstrous stereotypes and depersonalisation Black men continue to face. Smith’s print Do, Please. A Happy Ending (1987), which depicts smiling adults and children at a wedding, suggests the enduring strength and support of multigenerational communities. There is comfort in seeing Black people depicted on their own terms, but this is tinged with a sadness that context in which these works were made has not progressed as much as it should. Nevertheless, the show provides hope and tactics for ensuring that the more things change the less they remain the same.

The more things change… at Wolverhampton Art Gallery, through 9 July