What balance of the expected and the unexpected will bring crowds through the museum’s doors, two decades after its founding?

Since its founding in 2005, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej, or MSN) has been a hub of ambitious programming, initially operating from a former furniture store before moving to a pavilion on the bank of the capital’s Vistula River. In October 2024 it finally opened a permanent home, for its collection of 4,300 international and regional artworks from the 1950s onwards, on the northeastern corner of Warsaw’s Plac Defilad (Parade Square) – a place of gathering since its creation during the 1950s. The new MSN building stood relatively empty until February this year, when the institution unveiled an inaugural exhibition titled The Impermanent: Four Takes on the Collection, and has drawn the usual conservative scorn about contemporary art and architecture. A three-year strategic partnership with automobile company Audi and the displacement of local traders who formerly occupied the site has also provoked uncomfortable discussions. Underlying all this is the more fundamental question, why build such a museum today? That its opening weekend saw over 14,000 visitors might speak for itself, but MSN proves that this question is not met with easy or universal answers.

The building’s low-slung, minimalist form, which, depending on your perspective, exudes ‘quiet luxury’ or evokes a branch of IKEA (whose global domination began with the exploitation of Poland’s forests during the 1960s), seems in keeping with Warsaw’s current mode as a capital of big business and fashionable hospitality. MSN has years of experience negotiating and contextualising Poland’s divisions and historical traumas. It feels significant that its new building opened a year after the electorate’s rejection of the long-reigning rightwing government, which had commandeered the cultural sector to an alarming degree. While explicit gestures of ‘decommunisation’ have been made across the political spectrum to populist ends, MSN engages in a more nuanced exchange with the square’s soaring Stalinist Palace of Culture, which endures like the architectural equivalent of an ageing diva: awful but iconic.

Meeting visitors on the first floor as they travel around a dizzying, Escher-like central staircase, and positioned towards the Palace of Culture (visible through an expanse of glass), is Friendship (1954), a rare sculpture from the less well known Social Realist output of Alina Szapocznikow, who is generally celebrated for her later experimental works. Imposing in patinated bronze, it depicts a Polish and Soviet worker side by side in an embrace, but their other arms, which had extended outwards to hold a banner between them, were lost after the sculpture’s removal from the palace’s entrance hall during the 1990s. There is an ironic gesture in the sculpture’s placement, which could be waving (with absent arms) to its place of origin. This came to mind during MSN’s opening weekend via an artistic (though not art in any attributable sense) installation of cabbages – not ‘ornamental brassica’ but actual thumping kapusta – along the bar of the museum’s café. Fashionable floristry or a knowing, tender ‘wave’ to Eastern European clichés? Or both? Hanging above were paintings by Karolina Jabłońska of homemade bottled pickles, evoking the trope of słoiki (also the collective title of the paintings, dated 2024) – meaning ‘jars’ in Polish – the derogatory name used by city folk for migrants from the Polish countryside.

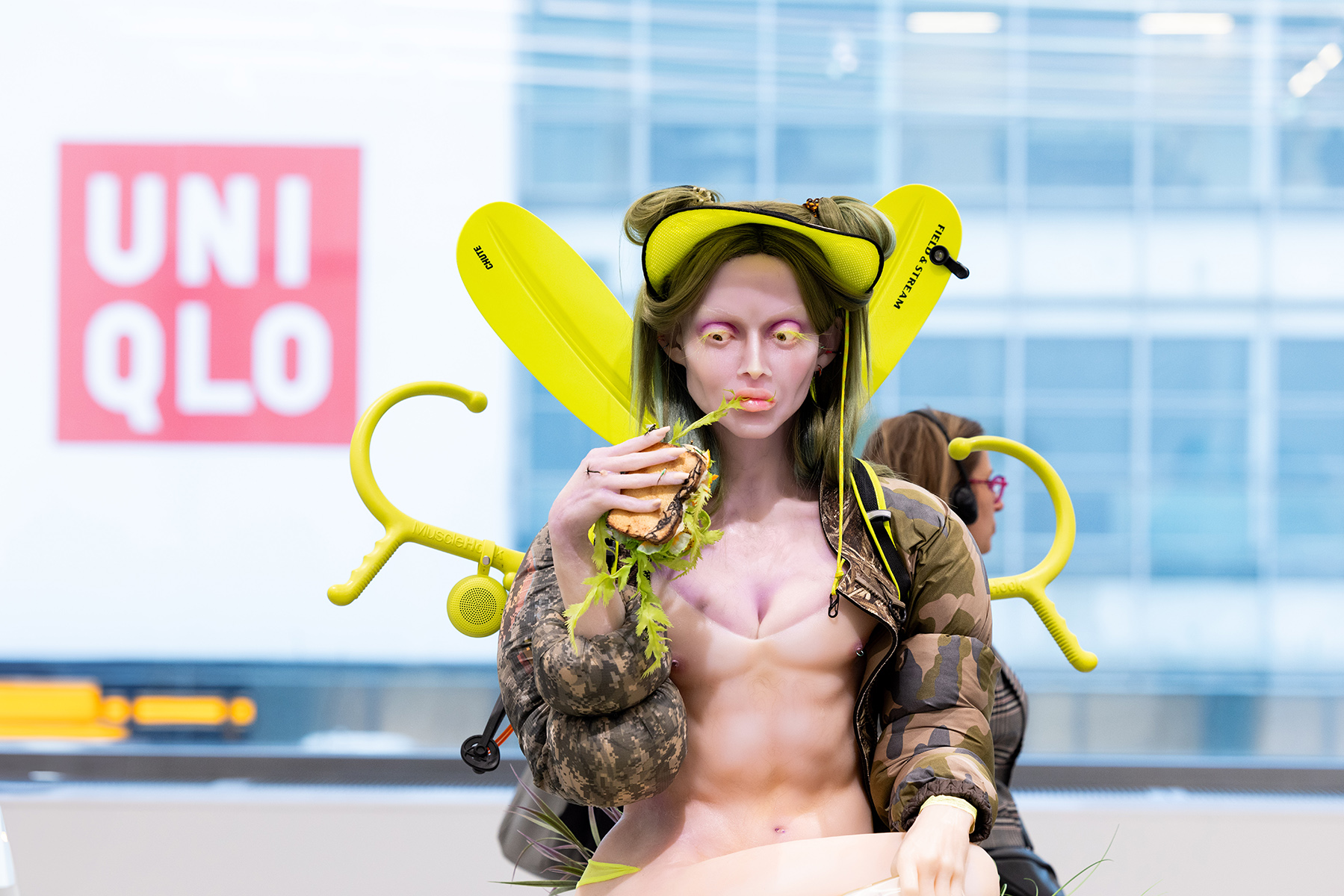

The exhibition catalogue features plenty of academic introspection about museology and politics, but there’s an insouciance at MSN, an instinct for drama and challenge that seems tapped into its public; a public that is acutely aware of its precarity at the eastern border of Europe. Crowd-pleasers and disturbers abound, from Canadian artist Tau Lewis’s Angelus Mortem (2021), a monumental ‘big cat’ head made from discarded furs, to the dystopian demigoddess of Swedish sculptor Cajsa von Zeipel’s mixed-media Friends with Grapefruit (2020), her piercing stare fused onto a society still awaiting the reestablishment of reproductive rights. In one of the exhibition’s four ‘takes’, Dark Planet: Art, Spirituality, and Future Coexistence, an untitled, moving vanitas tableau from 2014 by Northern Irish artist Cathy Wilkes is pertinent to a land also dominated by Catholicism and home to nearly one million Ukrainian refugees. Szapocznikow’s surreal sculptures of the 1960s/70s, lips and breasts sculpted from industrial waste materials, are expected in the section titled Synthetic Materialities: Body, Commodity and Fetish from the Cold War to the Present. What is not expected is the way in which Szapocznikow – when exhibited alongside other women artists from around the globe via this curatorial lens – takes flight from typically sombre presentations of her work, rooted in Holocaust trauma, in a way that is expansive and comradely, strangely joyful. For the moment, this feels like the point of Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art, where permanence might finally have a form but is rooted in a spirit far stronger than concrete.

Phoebe Blatton is a writer based in Berlin

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.