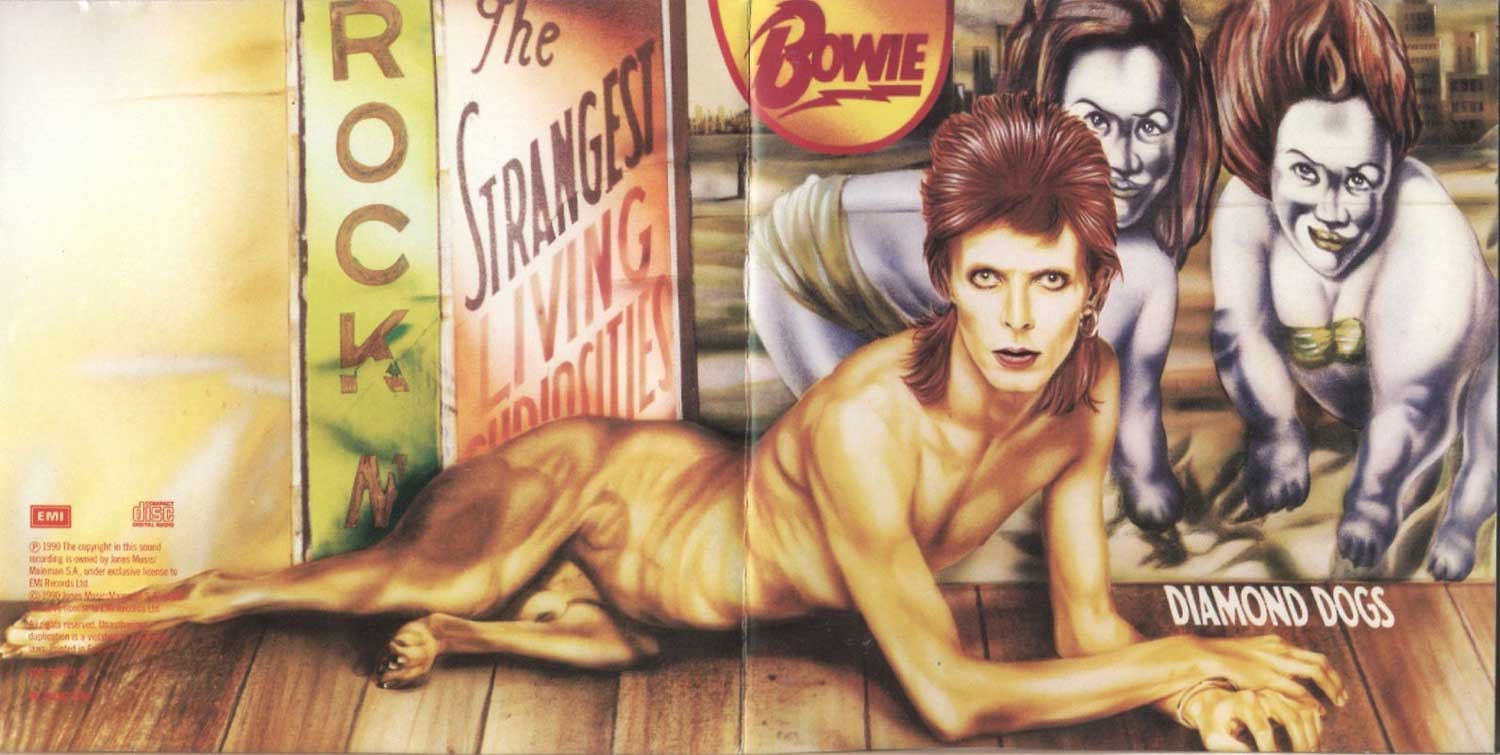

On the eve of the album’s release by RCA, the cover for David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs (1974) was presenting problems. It featured Bowie hybridised with a dog, and the record company was convinced that the graphic rendering of the canine’s genitals would cause offence in the conservative radio and retail climate of the time. Consequently, and at the 11th hour, executives ordered that the detail be airbrushed out. Copies of the original version – apparently never released, but ‘leaked’ onto the market without a disc inside – are now extremely rare, with collectors willing to pay $6,000–$10,000 for the few examples that exist.

We know that censorship creates desirability, and the prices these covers fetch are proof that the occluded object generates curiosity and wonder. the Diamond Dogs case shares similarities with the recent ‘banned’ Kanye West cover by George Condo (see last month’s column), yet differs in one important respect. Whereas the West cover was merely censored, the bowie cover was manipulated – visually doctored, pictorially castrated.

‘The only problem with the project was that they removed the prick’, commented Belgian artist Guy Peellaert, who was responsible for the cover painting (but not the later adjustment). ‘I thought it was very sad.’ however, the controversy did stir up further interest in Peellaert, who had already achieved a degree of fame for the collaborative art book Rock Dreams (produced, with text by Nik Cohn, in 1974). This collection of unearthly and surreal images of rock musicians in fictional, often bizarre situations (see the Rolling Stones in Nazi uniforms being entertained by naked prepubescent girls) confirmed Peellaert’s status as an artist to the stars: the Stones went on to commission an album cover off the back of the Nazi tableau (with Mick politely enquiring what he was driving at with the imagery), Jack Nicholson bought almost all of the paintings and Bowie roped him in for the cover of Diamond Dogs – the concept album that worked through the end of his glam-rock phase.

The music on the album is laced with apocalyptic imagery and references to Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), making Peellaert’s sensibility a good fit, with the cover following the template of the Rock Dreams collection in many stylistic ways. all Peellaert’s paintings of the musicians have an ominous, doom-laden atmosphere; they may be rock ‘dreams’, but hardly anyone ever smiles in the book – even the portrait of chirpy Scouse songbird Cilla black has an air of menace, as she sits knitting incongruously outside what looks like a corner shop, watching a white Rolls Royce creep grimly up a darkly terraced, symbolically deserted street – like a de Chirico painting set in Liverpool.

The painting style of the portraits is uniformly photographic if not cod-photorealistic, the heavy use of black set off with a dash of psychedelic colour adding a kind of kitsch horror to the palette. they use a halting, collage-based compositional style in which the characters seem to have no relation to one another, even while in the throes of rock excess. Yet today, a few of the paintings somehow manage to maintain a vivid, contemporary feel: Janis Joplin dead in an empty room is one example, looking like a collaboration between Margherita Manzelli and George Shaw. another such work sees Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson as a clownlike paedophile on a park bench, leering at a little girl (a scene pulled from the lyrics of the 1971 Jethro tull song Aqualung). If spotted in a show in London, new York or berlin this year, these two paintings would seem right at home – nearly 40 years after they were made.

At odds with his aristocratic ancestry, Peellaert (who died in 2008) was attracted to countercultural subversion all his life. It’s a thread that runs through his largely pop-centric oeuvre, encompassing graphic novels, film posters (Taxi Driver, 1976) and nightclub design as well as painting and drawing. the editing out of the dog’s genitals was ultimately the disappointing but predictable act of a mainstream that rarely failed to let him down. Yet maybe the elite status of the handful of original Diamond Dogs covers would be Peellaert’s cup of tea after all; in his cryptic foreword to Rock Dreams, Michael Herr could almost be talking about the Bowie censorship: ‘Culture dream, where your wonderful taste won’t do you any good, love dreams where you don’t know who’s on the display and who’s the voyeur, or even if you really saw it or dreamed it’.