The colossal faces of young celebrities that towered over you in Richard Phillips’s recent show at White Cube Hoxton Square, in London, recall two generations of Pop Art and their attendant critical dialogues, maintaining structural and visual ties to the tradition (a mostly male one, with rare exceptions such as Pauline Boty) of Pop/photography- led painting. straightaway one thinks of James Rosenquist, Jeff Koons, Mel Ramos and Chuck Close. With this, you get a cogent critical family tree, but you also get a blast of repulsion into the bargain: the monolithic smugness of high-profile pinup types, shown against backdrops plastered with luxury brand logos and painted (seemingly) photorealistically, is hard to like at first, presenting what initially feels like yesterday’s news – announcements of the cult of celebrity’s codependency with mass reproduction and high-end material consumption. Then something else happens.

Standing and looking at these paintings is an activity that radically undermines and updates the heritage of this kind of pop-cultural critique. In a skilful about-face, things quickly fall apart. The instantaneousness of complete recognition – of celeb, posh brand, photorealist painting – gives the temporary impression that the painting itself is a willing participant in this logic, mimetically pimping out its own desirability to smoothly complete the circuit of commodified voyeurism. but it’s a reaction as fleeting as the photo opportunity that the works originate from, a pat response based on the ubiquity of past (though related) forms of art. Suddenly the works press upon you a uniquely physical urgency and a highly nuanced cerebral chill. The material technology of the paintings works its ancient charm – they are highly sophisticated and compelling in execution – generating a reflexive short-circuit with the culturally established, symbolic properties of the image. We are vertiginously, dizzyingly invited to consider the paintings in ways that sit uneasily with the iconic heads they present to us, and at that point, the tag ‘photorealism’ evaporates, becoming another trite response, a form of lazy labelling.

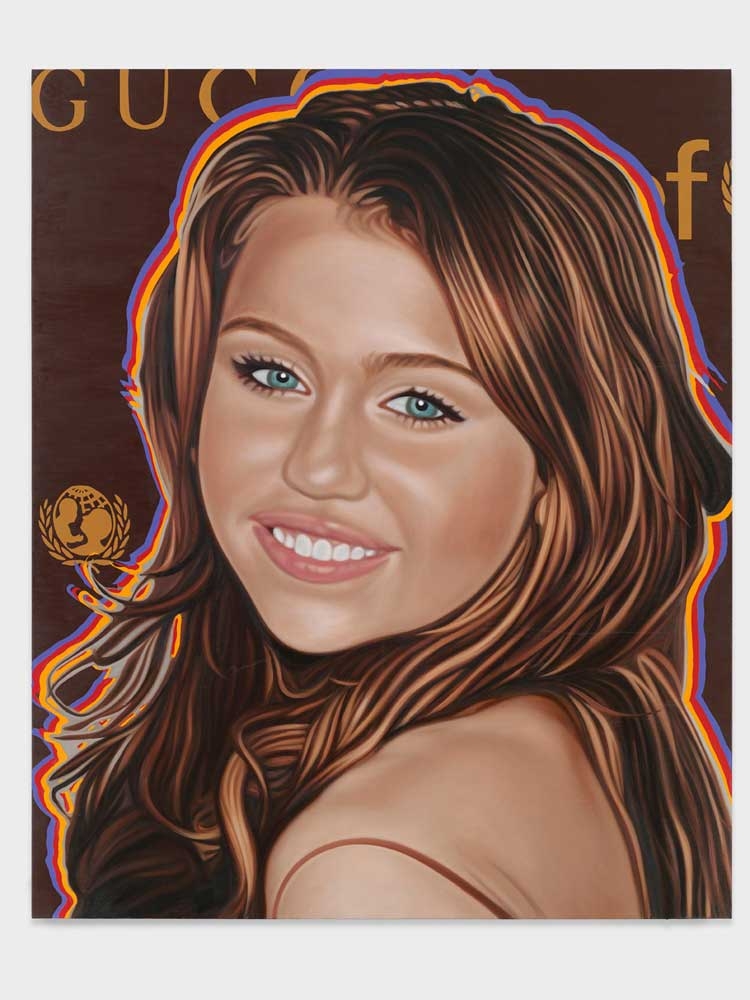

It happens in a moment of parallax – that is, the apparent displacement of an object caused by its observer changing viewing position. The viewer’s moving gaze – brought about through the theatrical permissions of gigantic scale (they are 240cm high) – discloses a deeper dimension in the work as we secure a relationship with the image through a slowly unfolding sequence of visual glitches. Zac Efron starts to look funny round the chin; Chace Crawford’s eyebrows seem a bit big; Miley Cyrus is more chipmunklike than usual; and almost all of the eye details – conventionally a point of identification and stability – appear inaccessible, abstracted, and unseeing. such incidents move the gaze round the picture rather than settle it, providing not resolution but a fracturing, a dislocation.

Philosopher Slavoj Zizek details an ontological dimension to the mechanics of parallax that closes in on such visual experiences. for Zizek, writing in his 2006 book The Parallax View, the ‘parallax gap’ is a ‘pure’ minimal difference that divides the object from itself, a kind of ‘X factor’ that eludes the symbolic grasp of the spectator. in a neat illustration of the idea, Zizek introduces a scene from Henry James’s 1892 short story ‘The Real Thing’. The narrator – also a painter – arranges for a pair of aristocrats to pose for his illustrations for a deluxe book edition. Yet in the resulting drawings, the characters somehow seem artificial. To resolve this, the painter resorts to the services of less noble models, finally striking the right tone with a couple of vulgarians whose imitation of the high-class pose is more convincing than the real thing. Parallax becomes the definition of a sort of pictorial magic, the DNA of what we mean by the phrase ‘artistic licence’. The gulf of reality inherent in parallax gives the mind the space to perceive and give meaning to difference, strive for synthesis, become involved in the image, and perhaps take possession of it.

In deploying both the classic technique of scaling up an image from a drawing (which vitally involves the harbouring of mini-errors and lost information which only becomes apparent when scaled up later), then vastly increasing the size of the image, Phillips has activated a viewing experience that manages to take our saturated awareness of the people themselves as a point of departure. In the end, Hollywood’s young and powerful become less convincing as icons and more convincing as paintings. and in so marginalising his celebrity subjects through parallax, Phillips generates his own brand of equality between the viewer and the image, predicated on a transformation of the experience from abject recognition into free philosophical speculation.