Can documentary cinema intervene in preventing the repetition of past injustices?

“We were abandoned to ourselves as the whole world was watching”, says a father, the tears wet on his face. His testimony features in Jenin, Jenin, a documentary film by the Palestinian actor and filmmaker Mohammad Bakri. Made in 2002 after the Battle of Jenin of that year – where over 50 Palestinians were killed and hundreds of houses were destroyed by an Israeli assault – the film comprises interviews with residents of the Jenin refugee camp (established in the Israeli-occupied West Bank in 1953 to house Palestinian refugees expelled from their homes by the 1948 Palestine War). The Israeli government refused to permit a UN fact-finding mission to enter Jenin. Films like Bakri’s, shot from the inside by those who themselves lived through the same horrors, offer intimate insight within otherwise tightly controlled conditions. There is no narrative voiceover, only the words of the camp’s residents.

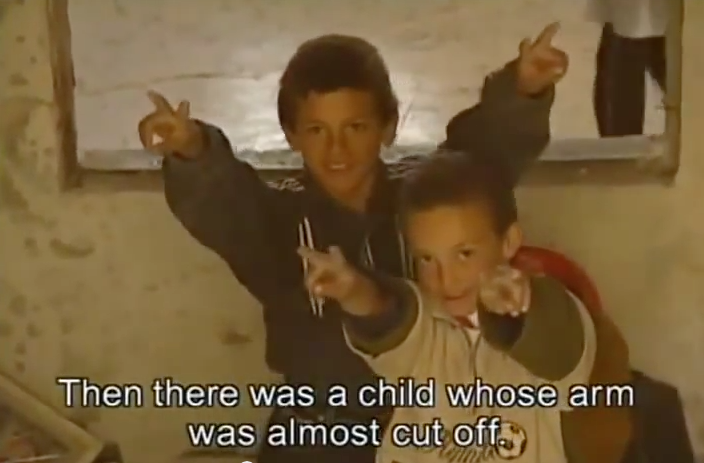

A Palestinian doctor describes the destruction of a hospital, children made to demolish their own homes at gunpoint, doctors who couldn’t save their own children. People recount forms of violence accompanied by sadistic acts of humiliation by the Israeli military. The predominant visual impression given by the film is the colour of rubble – that peculiar lifeless dusty grey covering entire houses, buildings and streets flattened or hollowed out by bombardment and bulldozers.

Jenin, Jenin depicts and archives, through interviews, recorded footage of Israeli soldiers, and detailed visuals of the destruction of Jenin camp, forms of extreme, gratuitous brutality that have been repeated and intensified in Gaza since the event of 7 October 2023. The testimonies collected in Jenin, Jenin were recorded after the violence concluded, but the atrocities in Gaza are reported live by journalists who are themselves the targets of Israeli assassinations, and through the social media feeds of people trapped within an unfolding genocide. Both record an insatiable appetite for violence that is seemingly not satisfied with killing alone, but invents new forms of inflicting hurt and humiliation.

The residents of Jenin camp are astute political observers in Bakri’s film. They see the hypocrisy of the world’s treatment of Palestine: “Why are all the regulations of the world applied to us only, and not to the Israelis?” Over and over again, the camp residents exclaim in disgust that western governments and media are prepared to call them terrorists without questioning the actions of the Israeli state. Palestinians, Edward Said argues in A Question of Palestine (1979), are often figured as ‘non-existent’. The description of Israel as ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’ – a longstanding Zionist slogan – and its former prime minister Golda Meir’s statement in 1969 that there were no such thing as Palestinians are but two examples of this. In addition to this denial of the existence of Palestinians as a national group, Said writes that they are repeatedly and intentionally characterised as terrorists. This has the effect of occluding the violence they face, as well as their political demands for a homeland.

Last month, I watched Jenin, Jenin as part of the biennial SAFAR Film Festival, a fortnight of film programming showcasing cinema from the Arab world, in multiple venues across nine cities in the UK. This year’s edition put Palestine at the centre of its programming, alongside films from Lebanon, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Sudan and Syria, to pose the question of whether cinema can intervene in preventing the repetition of past injustices. While films like Jenin, Jenin cannot put an end to Israeli aggression, they remind us that what we are witnessing in Gaza is part of a long history. They are an act of memory against forgetting.

The atrocities committed in Jenin in 2002 also haunt Carol Mansour and Muna Khalidi’s A State of Passion (2024), which depicts the life and work of the British-Palestinian surgeon Ghassan Abu-Sittah during the 45 days that he worked at Al-Shifa and Al-Ahli hospitals in Gaza. Based in London, Ghassan Abu-Sittah’s wife Dima was born and raised in Gaza. In September 2023, they were visiting family there; a month later, Gaza was under attack. His experience has made him an important witness to the genocide, a role that he has since carried forward through his advocacy, providing testimony to the International Criminal Court, speaking at protests, and running the Ghassan Abu Sittah Children’s Fund. In the film, we watch Dima as she learns the Israeli security forces have destroyed her family home, detained her father and killed her uncle – all while the film was being shot. At one point in the film, she says: “It’s not just a genocide, it’s a destruction of memory.” The films shown at SAFAR resist such destruction; they are forms of remembering and witnessing realities that are subject to erasure and political disavowal.

These two documentaries also clarify the stakes of present-day politics in the UK. While the SAFAR film festival was underway, Yvette Cooper, Secretary of State for the Home Department, proscribed pro-Palestinian direct action group Palestine Action under the Terrorism Act, due to their ‘long history of unacceptable criminal damage’. Palestine Action’s primary targets have been the UK manufacturing facilities of Elbit Systems, Israel’s biggest weapons manufacturer. The proscription order, published in Hansard, repeats the phrase ‘damage to property’, as though the only moral and ethical impulse legible to the British government is the sanctity of property, even over claims to human and indeed planetary life. Indeed, it would be difficult to find a more succinct summary of the logic of colonial capitalism than in the rhetoric of the order proscribing Palestine Action. As the subjects of Jenin, Jenin and A State of Passion assert their right to remain on their land, their commitment to rebuild the houses and neighbourhoods, and as they recall their beloved homes, trees and gardens, they are describing not a property relation but a living and loving attachment. These are places that contain hopes, dreams, memories and entire histories.

Akshi Singh is a writer and psychoanalyst based in Glasgow and London