These works from the collection of the Kadist Foundation orbit around the theme of plantations, and wonder if we’ll ever shake off its legacies

The Plantation Plot revolves around a double meaning: at once the physical plantation plot and also the global narrative surrounding plantations in general. Or in the exhibition’s own words, ‘(refiguring) the plantation plot as both story and place’, an idea that the exhibition’s curator, Lim Sheau Yun, explicitly borrows from Jamaican critic Sylvia Wynter’s essay ‘Novel and Narrative, Plot and Plantation’ (1971). The exhibition bridges works by Malaysian and Malaysia-based artists with works from the collection of the Kadist Foundation that orbit around the theme of plantations, attempting to illustrate how, in Lim’s words, ‘we are still trapped in the plantation plot’s spellbinding reality… and its structuring power’.

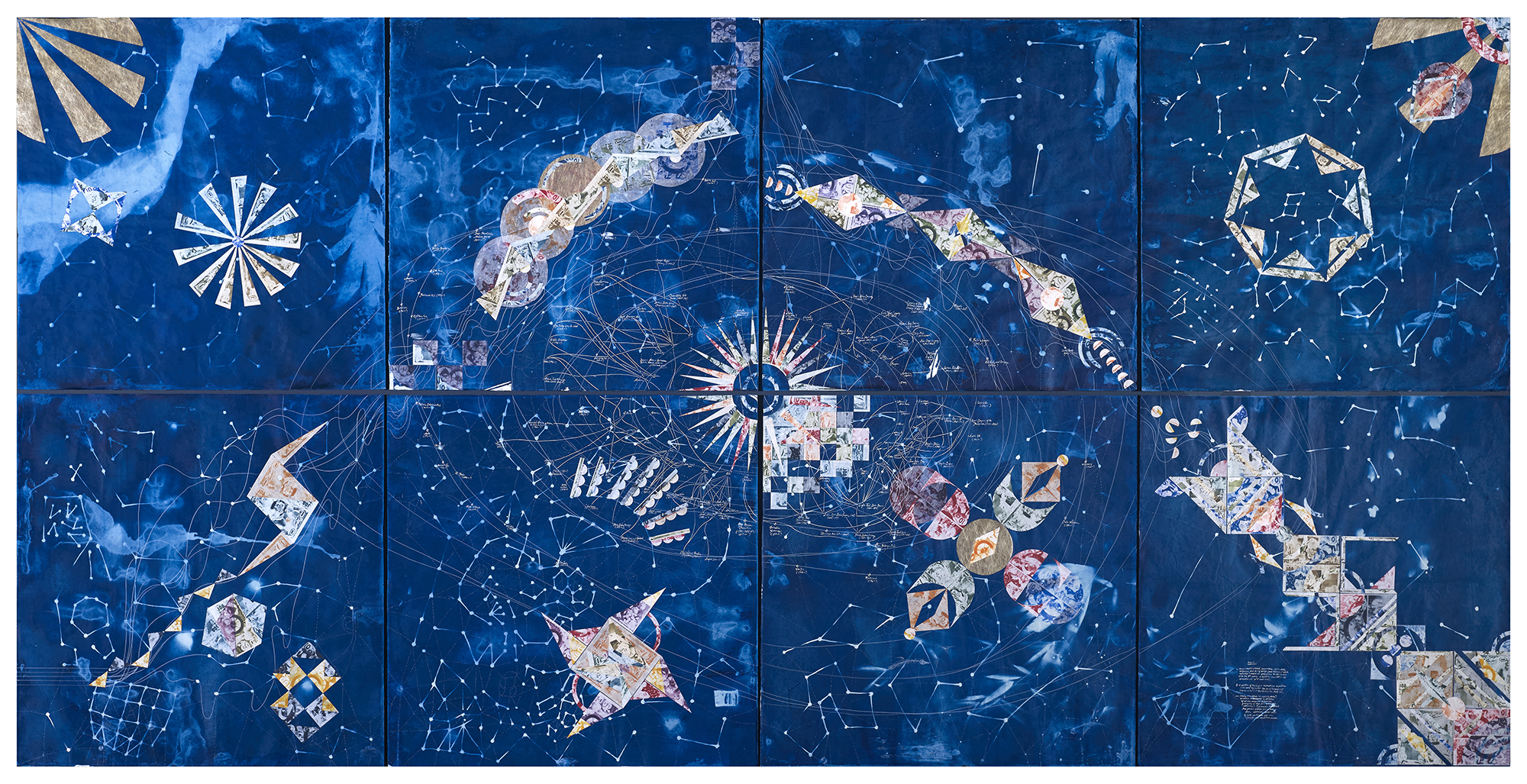

Anchoring this argument is a large, mixed-media work by Connie Zheng, hung on the gallery’s central wall. As It Is: Nothing Lasts Forever (2025) depicts a solar system printed in cyanotype in which the names of Fortune 500 and FTSE 100 companies take the place of planets, interspersed with labels of various plantation products (rice, maize, rubber) and historical trading companies. Instead of stars, collaged constellations of currency float across the blue universe. Lines and arrows crisscross the solar system, connecting historical monopolies with present-day multinational corporations, crossing space and time to show how some of the latter evolved out of the former: how nothing has really changed. Mirroring Zheng’s piece on the opposite wall are two tapestries by Cian Dayrit made in collaboration with Henricus, Fever Dreams of Progress: Grease of Empire and Semi-feudal Order (both 2025), which feature studied phrases such as ‘neoliberal policies’ and ‘reliance to agrochemicals’ embroidered in a mind-map-like fashion similar to Zheng’s work. Both these works assiduously sketch out what the exhibition is attempting: showing how the legacy of plantations remains central to the narratives of many nations in the developing world today.

The Plantation Plot studiously reads its subject through multiple intersectional frameworks, including ecology and economics, postcolonialism, the impact of plantations on native and diaspora populations, and a gendered reading on the disproportionate treatments faced by female and male indentured labourers. It is an exhibition with an ambitious scope, bigger, arguably, than the space afforded by Ilham Gallery, with the result that, like Zheng and Dayrit’s text-heavy works, the exhibition, ultimately, becomes preoccupied with indexing relevant points rather than with providing an aesthetic experience.

As a result, there ends up being a tension in the exhibition between experience and edification. Its layout reflects the desire to explore the aesthetic, sensual possibilities of telling the plantation story – to provide ‘a somatic, sensory ground from which political economies can be retold’ as per the curatorial statement. But the wall texts, written in a more dry and theoretical manner, attempt to rein the artworks back into an academic critique of ‘capital’ and the postcolonial condition. The exhibition opens with striking energy and a whiff of the exotic, showcasing an array of Global Majority artists working across diverse contemporary mediums. Highlights include Corey McCorkle’s Pendulum (2016), an installation of Cavendish bananas; Noara Quintana’s Evenings of water, Dense forest: Patauá and Caeté and Dense forest: Mandioca e Tamba-tajá (2021), in which lamps made from natural Brazilian rubber emit a firefly-green glow; a tableau of gigantic mythical forest creatures based on Orang Asal folk legends, created by AWAS! MAWAS! in collaboration with Indigenous Malaysian schoolchildren; Izat Arif’s Tuan Tanah (Land Lord) (2025), featuring upright, dust-covered coffins with peepholes screening short videos critiquing Malaysia’s felda rural management system; and Taloi Havini’s Beroana (Shell Money) I (2015), a spiralling installation of ceramic disks replicating Pacific Islander shell currency.

The strong, multisensorial front tapers off where the exhibition dissolves into a melodramatic theatre of exploitation. Several works rely on heavy-handed imagery, such as Santiago Yahuarcani’s Castigos del caucho (2017), a series of paintings depicting gruesome scenes of torture based on his grandfather’s accounts of the Putumayo genocide of Indigenous Amazonians by the Peruvian Amazon Company; or Inauk S. Gullah’s Folk Art Ku Analisis Negeri Di Bawah Bayu (2012), which features schematic renderings of devils, angels, the snake from the Garden of Eden and the slogan ‘Jangan Membunuh’ (Don’t Kill). To be sure, these are worthy testimonies of oppression faced by the respective communities that each artist represents, but their literal and folksy manner feels out of step with the more contemporary modes found elsewhere in the show. The impression given is that these works were included to lend the exhibition emotional gravity, and to discipline its self-professed ‘somatic, sensory’ aesthetic tendencies.

Most of the works in the show deal with the past and the legacy of the plantation; only a handful attempt to deal with the reality of plantations in the twenty-first century. Minstrel Kuik’s Residence Time (2025) is a photographic installation of double-sided, oil-stained photographs. One side is printed with candid photographs of the residents of palm oil estates in the artist’s hometown of Pantai Remis, Malaysia, zipping across dirt roads on motorbikes. The other side is printed with photographs of tropical evening skies, superimposed with the red streaks from motorcycle taillights: the palm oil that the photos are soaked in has made the paper translucent, allowing the images on both sides to bleed into one. Residence Time poignantly captures daily life in the plantation’s monotonous landscape, without the drama of other works in the show; filtered through Kuik’s lens and the glaze of palm oil, the photographs lend plantation life a cinematic touch of romance and tragedy.

The plantation ‘plot’ is still a defining moment in the histories of many nations in the developing world today, including Malaysia, where the economy is sustained by rubber and palm oil. This exhibition makes a valiant, if flawed, attempt to do justice to the myriad nations that have had their histories, cultures and ecologies disrupted by colonialism and the introduction of the plantation’s banalising totality.

The Plantation Plot at Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, 20 April – 21 September

From the Autumn 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next: Kuala Lumpur’s King Collectors