Hatty Nestor’s study of ethical portraiture is an effective form of consciousness-raising, demonstrating an assertive, political urgency

Hatty Nestor’s salient and sensitive investigation into the representation of individuals incarcerated in the US opens with a quote from Judith Butler’s Precarious Life (2006): ‘Those who gain representation… have a better chance of being humanized… those who have no chance to represent themselves run a greater risk of being treated as less than human’. Butler uses Emmanuel Levinas’s philosophy about ‘the face’ and ‘the Other’ as a framework, writing that ‘to respond to the face… means to be awake to what is precarious in another life’. Nestor also takes a Levinasian approach to the ethics of looking and visibility, contending that when an artist documents an individual, they inherently enter ‘a position of accountability and responsibility… when a moral obligation to others, by default, should take priority over the so-called individual self’.

Across six chapters, Nestor interrogates manifold depictions that include CCTV footage, DNA profiling and media images, in addition to conducting extensive interviews with artists who have made portraits of incarcerated, missing and wanted people in gestures of solidarity and resistance. Nestor’s essayistic, voice-driven narrative is an effective form of consciousness-raising, demonstrating an assertive, political urgency to the issues, rather than presenting an abstract debate. She is transparent about her anxieties surrounding the ‘ethical conundrum of portraying another person’, cognisant of ‘the fine line between “research” and voyeurism’, questioning rather than didactic in her approach.

In her foreword, Jackie Wang suggests that the practice of ethical portraiture requires ‘circulating images that counter the state’s representational repertoire’, thereby creating ‘counter-images’. The ‘counter-image’ brought to my mind James E. Young’s theory of the ‘counter-monument’, defined in The Texture of Memory (1993) as a rebuttal to the traditional, passive memorial. The counter-monument is active, it can ‘provoke’ and ‘demand interaction’. Nestor similarly defines an ethical portrait as ‘integral and empathetic, [challenging] marginalisation’, allowing individuals who have been dehumanised by the prison-industrial complex to regain control and demand agency. It is the counter-portrait to the mugshot, which demands subjects to ‘act as if they are already corpses’, or the courtroom sketch, where ‘subjects are given no voice, no say in how they are portrayed’. Forensic technology, such as facial recognition software, is shown to be an oppressive surveillance tool with historical roots in the pseudo-scientific nineteenth-century method of categorising criminals by their physiognomy.

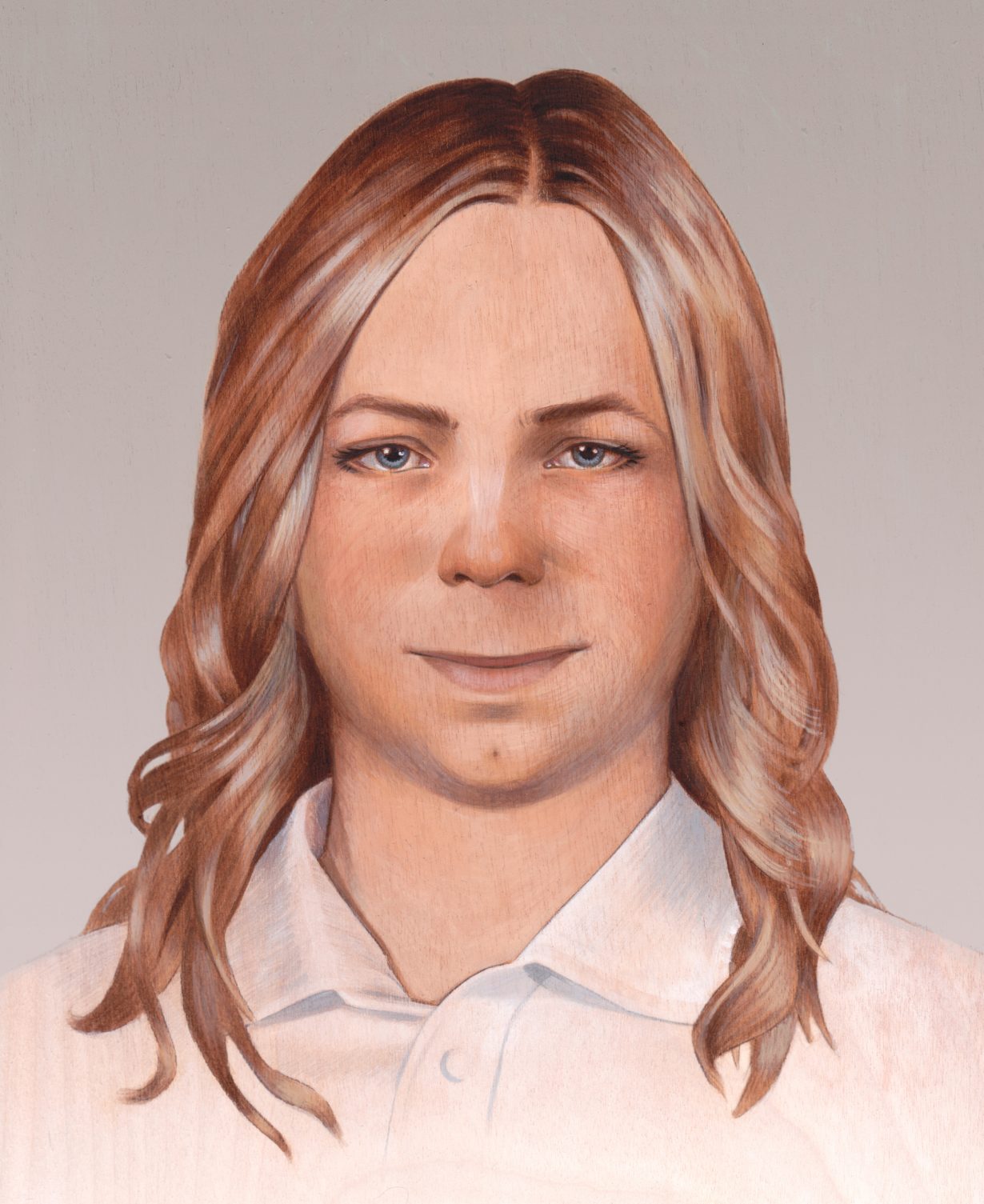

Two chapters are dedicated to artist portraits of the activist and whistleblower Chelsea Manning, by Alicia Neal and Heather Dewey- Hagborg respectively. Transgender inmates are subject to brutal mistreatment and violence within the carceral system. In 2014 Neal was commissioned by Manning’s Support Network to paint a portrait that aligned with her chosen gender presentation, as her only media representation was a misgendered military photograph. This new image was circulated, acknowledging her selfhood and functioning as a form of reparative justice. In Radical Love (2015) Dewey-Hagborg created 3D-printed portraits with forensic methods of representation, using DNA samples from swabs and hair clippings that Manning sent her. Nestor argues that this artwork liberates Manning’s image while also dismantling the hegemony of genetic data.

People of colour, women and individuals from poorer backgrounds face lengthy sentences for minimal crimes, whereas large corporations avoid criminalisation. Jeff Greenspan and Andrew Tider’s 2016 activist project Captured: People in Prison Drawing People Who Should Be addressed these discrepancies, however ‘the inmate is only rendered through the portraits of those who are free’. Alyse Emdur’s Prison Landscape (2005–13) series fully engages with their visibility, photographing inmates in front of painted backdrops. These artificial scenes depict ‘imagined existences of nonconfinement’ (waterfalls, beaches, sunsets), enabling prisoners to assert ‘their individuality as a gesture towards freedom’. The power of their imagination can exceed the regulated space of the prison. Emdur’s work provokes Nestor to raise the importance of solidarity, ‘a position that demands to be revisited time and time again, until we find alternative avenues of representation for the marginalised’.

Ethical Portraits: In Search of Representational Justice by Hatty Nestor, Zero Books, £10.99/$16.95 (softcover)