This group show at Croy Nielsen in Vienna traverses the unstable borderlands of nature and machine

A beast rotates in jerky movements at the centre of The Shed, a four-person show guest-curated by Karen Archey. The mechanical roar and heavy mass of Nina Beier’s Beast (2024), a dark brown rodeo bull, reverberates uncomfortably in the viewer’s body: this manmade entertainment machine stages the macho striving for domination in the bluntest possible terms. On its back, though, the animal carries plastic jugs filled with infant formula derived from cow’s milk. The clash between the natural and the industrially produced is stark. Here, the consumable female body and questions of gender relations within parenthood intersect with the exploitation of animals – who, despite the bull’s apparent resistance, cannot throw off what binds them.

Beier’s work resonates with three 2018 wallworks from Alice Channer’s photo-relief series Soft Sediment Deformation, which also traverses the unstable borderlands of nature and machine. What at first resemble blowups of fish- or snakeskin turn out to be glitchy images of rock formations, stretched and distorted. The planet meets digital processing and the extractive logics of industrial production. Printed onto heavy crêpe de chine and pleated with fast-fashion techniques, these works are delicate yet unsettling in how they alienate and confine nature, reducing it to an ornamental pattern.

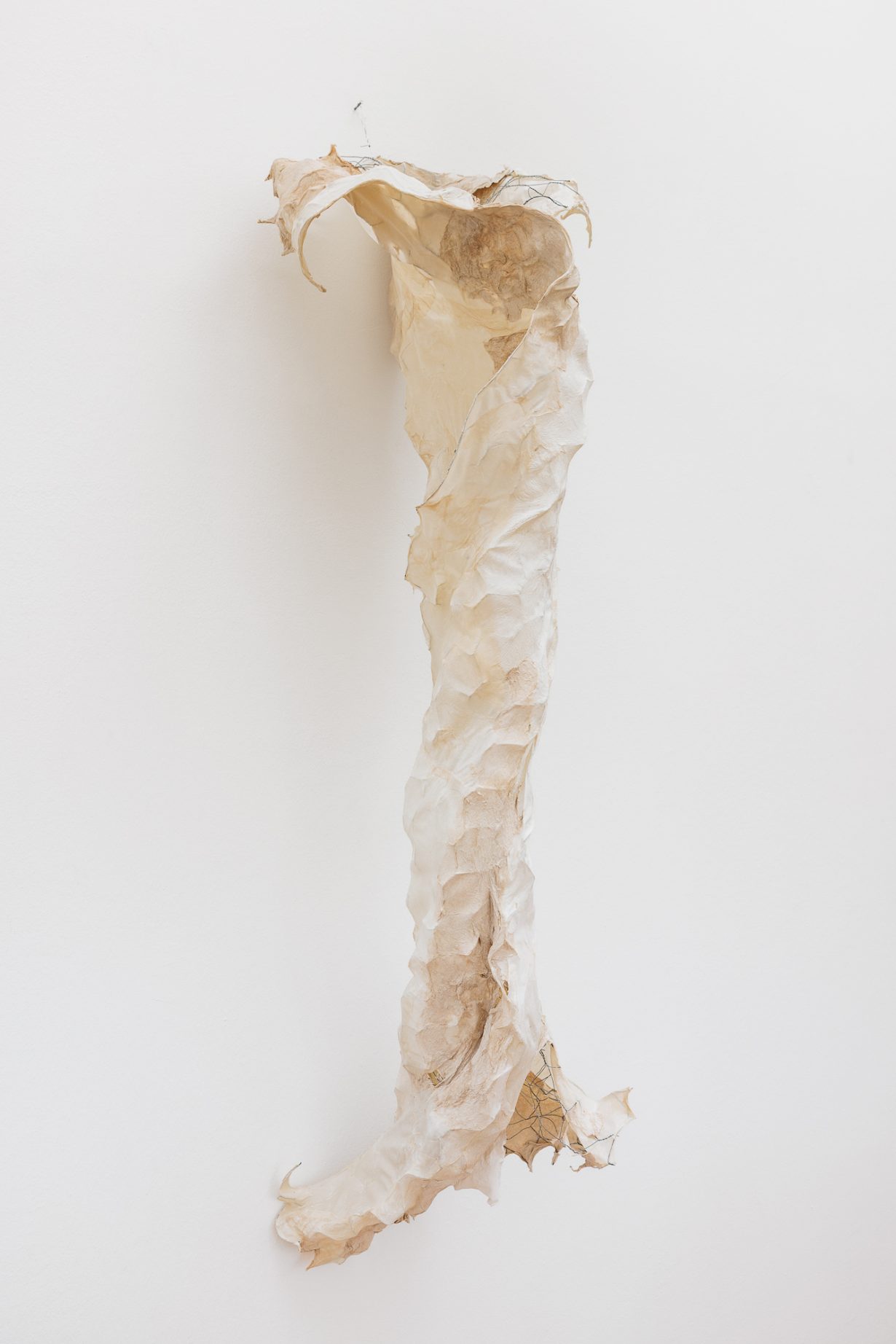

Beier’s and Channer’s positions are framed, in turn, by pieces from two American artists of an earlier generation, Lynda Benglis and Judith Bernstein. The phallic screw-tool hybrid of Bernstein’s monumental charcoal drawing SCREW 5 (2014) faces Beier’s bull head-on, its black marks executed with insistent ferocity. Bernstein started this series in 1969, speaking forcefully to the persistence of patriarchal power until today. (The merging of machinic hardness with the organic body and the resulting aggressiveness of the imagery recalls Lee Lozano’s work of the 1960s.) A reference to the famous removal of Bernstein’s 1973 drawing Horizontal from a 1974 show in Philadelphia appears in the gallery office. The black charcoal drawing Small Horizontal Number 8 (1973), where the tip of the depicted penis is only vaguely recognisable through the expressive mark-making, anchors the surrounding works in a historical context – one whose relevance has hardly diminished, given the renewed political pressure from the far right on progressive positions in academia and the arts today. Benglis’s sculpture Bone Ribbon (2015–16), meanwhile, appears more ambivalent. Its twisting, opening form suggests, by turns, a phallus and a frail flower; its handmade paper skin is vulnerable, stretched over sharp chicken wire, punctured with openings and abrasions. A piss-yellow scrap juts out at the base. Benglis brings matter to the edge of abjection: Bone Ribbon, hovering between fragility and violence, feels like a punch to the gut.

Archey, who is also curatorial director at Düsseldorf’s Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, a major German art collection, didn’t write a conceptual text for the exhibition but a short poem, and this arrangement of works, while exploring power dynamics in boldly visceral terms, similarly captivates in its looseness and experimental nature. The Shed is part of the annual ‘Curated by’ festival organised by Vienna’s commercial galleries, and its sketchy logic resonates with this year’s theme of ‘Fragmented Subjectivity’. Neither the concept nor the works seek wholeness or the visitor’s undisrupted acceptance. Whereas Benglis’s piece lays bare its own constructedness, the printer’s registration marks that are usually cut from the fabric remain visible along the upper edge of Channer’s works. The mechanical apparatus of Beast is likewise integral to its presentation, while Bernstein’s unframed painting refuses illusionism: the heavy linen of the picture support drapes onto the gallery floor as an installation in its own right. What remains is not coherence but vibration – an uneasy resonance that insists on the necessity of loose ends.

The Shed at Croy Nielsen, Vienna, through 4 October

From the October 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.