How one street in Downtown New York became a centrepoint of artistic invention

Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate.

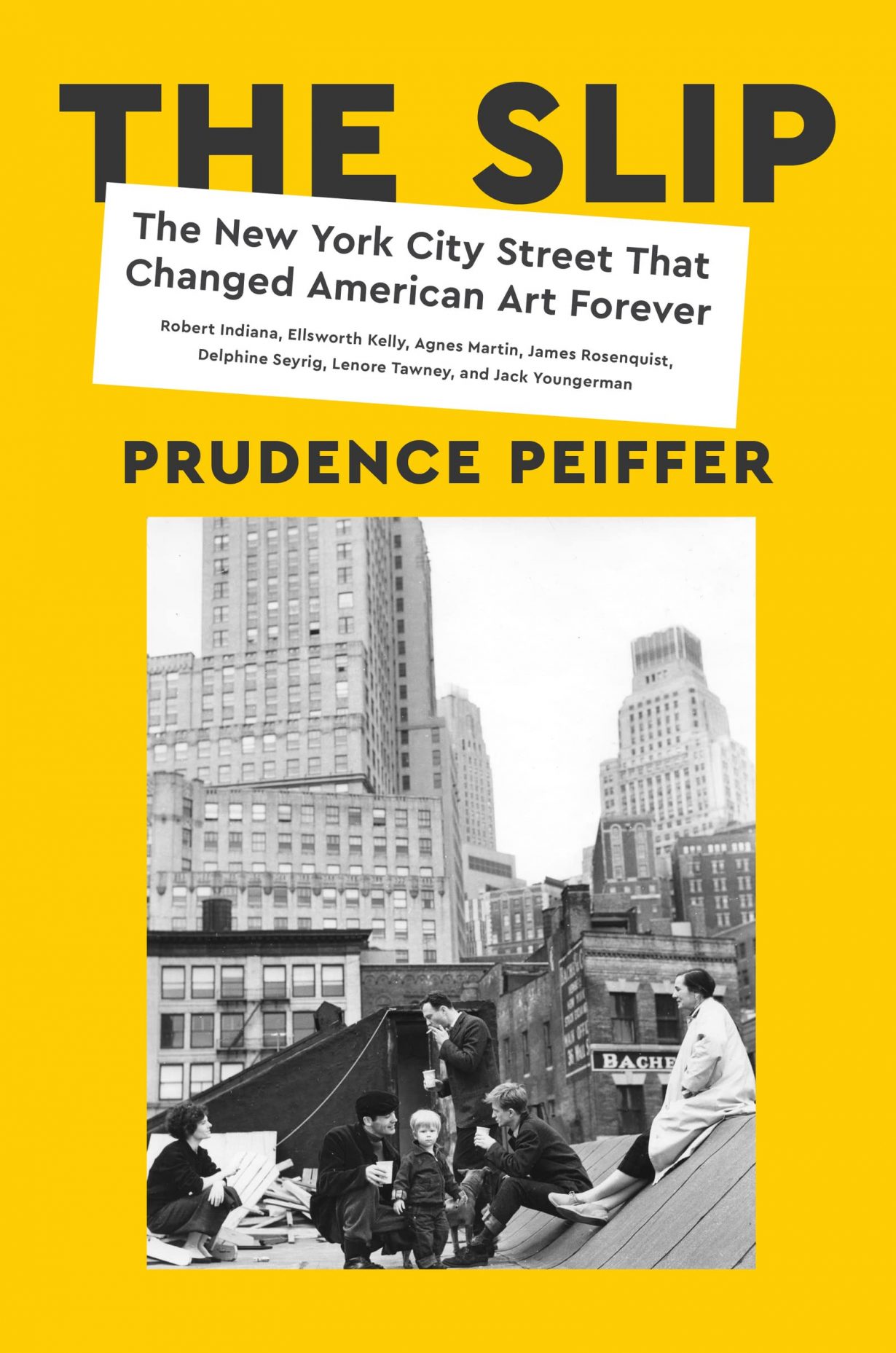

From the mid-1950s to a decade later, one dead-end street in Lower Manhattan quietly hothoused seismic changes in American art. Amid the former sail-making warehouses of Coenties Slip, on the East River in what’s now the Financial District, a disparate group of artists – including Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Delphine Seyrig, Lenore Tawney and Jack Youngerman – gathered to live and work. From these unheated and unventilated lofts came innovations in post-Abstract Expressionist painting and sculpture – hard-edge abstraction (Kelly, Martin), Pop (Rosenquist, Indiana) – as well as in avant-garde cinema (in which Seyrig was a key figure). As opposed to Ab Ex, furthermore, the creative figures were often gay, female or both. In critic and art historian Prudence Peiffer’s meticulously researched and lucidly written memoir of the thoroughfare and its significant occupants, the street serves as a metaphor for a Manhattan art life that’s barely available anymore. Her story tilts the established trajectory of modernist art-history away from linearity and masculinism, and from narratives of standalone genius. Instead, the focus is on collective development and what Peiffer calls ‘little pathways of influence and intrigue’.

The Slip, from its title onwards, also serves as an embodied argument for the importance of place in understanding how art gets made. Time and again, Peiffer reports on how the new art emerged directly from the texture of the Slip. The even-keeled Kelly teased his abstractions from drawings of the avocado trees that he grew on the roof; Martin (who’s reported as saying, in 1950, ‘I don’t care who I have to fuck’ to succeed) made her first grid works by hammering nails into scavenged wooden panels and, additionally, found in the Slip the silence she needed to purify her abstract painting. Indiana sourced materials from the building itself, making proto-Pop assemblages like Coenties Slip Studio (1961); the acres of loft space allowed Rosenquist to work big. In pointing out that the artists could both support each other and withdraw to create new aesthetics, The Slip argues for the virtues of what Peiffer calls ‘collective solitude’; a condition of spacious mutuality, she notes, that’s inimical to the distractive digital atomisation of today.

The book’s evocation of the midcentury American artworld is accordingly a dispatch from a melancholically vanished realm, bringing it back to life via teeming detail; look here if you want to know exactly what groceries cost in Manhattan circa 1957, or how the broke artists got by (hosting workshops, tapping gas lines, allegedly collecting loose change from payphones in Martin’s case, borrowing lots of money from parents in Seyrig’s). It’s also an immensely satisfying read due to how it’s structured. At the beginning, Peiffer backs up a few centuries to evocatively limn the centrality of maritime trade to old New York. (Herman Melville mentioned Coenties Slip in Moby-Dick.). She asserts the importance of Kelly’s and Youngerman’s pre-New York sojourn in Paris, and how artists like Matisse and Monet impacted their aesthetics. Her gradually tightening narrative ticks off the meetings that bring her brilliant gang together in one place, judiciously assesses the importance of supportive figures like gallerist Betty Parsons and the role played by other luminaries such as Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol, and – of course – watches as the protagonists find success.

And then, inevitably, the party ends. As New York is transformed under Robert Moses’s urban planning, skyscrapers start going up on the Slip – all that’s left today is numbers 3 to 5 – and the artists have to get out. The author watches them go, mirroring earlier chapters in which she’d described each artist’s manner of arrival with dedicated sections that mark their departure and, finally, offer tight précises of their subsequent careers: everything the Slip gave them. In the end, Peiffer is careful not to be too prescriptive, or despondent, concerning what form a ‘collective solitude’ of today might take, but she doesn’t slide into lamentation. Admittedly, such a phenomenon probably won’t happen again in Manhattan’s Financial District. But The Slip, for all its immersion in a rebuilt past, nevertheless has a hopeful, toolkit feel: you leave wondering how and where such unseen but crucial communities might coalesce in the future.

The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever by Prudence Peiffer. Harper Collins, $38.99 (hardcover)