In Lightning Wheel, Collins refuses to be pigeonholed as an ‘artist-activist’ and instead leaves the politics of her colourful textile works open-ended

There are soft explosions in Liz Collins’s textiles. From the atomic nexuses of 12 embroideries and weavings, an energy both analytic and disco blasts its rays in joyous shades. The Brooklyn-based artist refuses to hold back on hues and textures, colouring cushiony surfaces with a blissful militancy. As a result, her works on display at Candice Madey, which are at once warm, carefree and unpredictable, simultaneously invite and disarm; they enact an effortless embrace of the everyday, as well as a tightly orchestrated celebration of an oblique and open-ended personal cosmology. Like a rock anthem or even a prayer, there is a devotion to a rhythmic order – perhaps inevitable in weaving – but just as the same words can be uttered differently, her works signal subjectiveness in each thread.

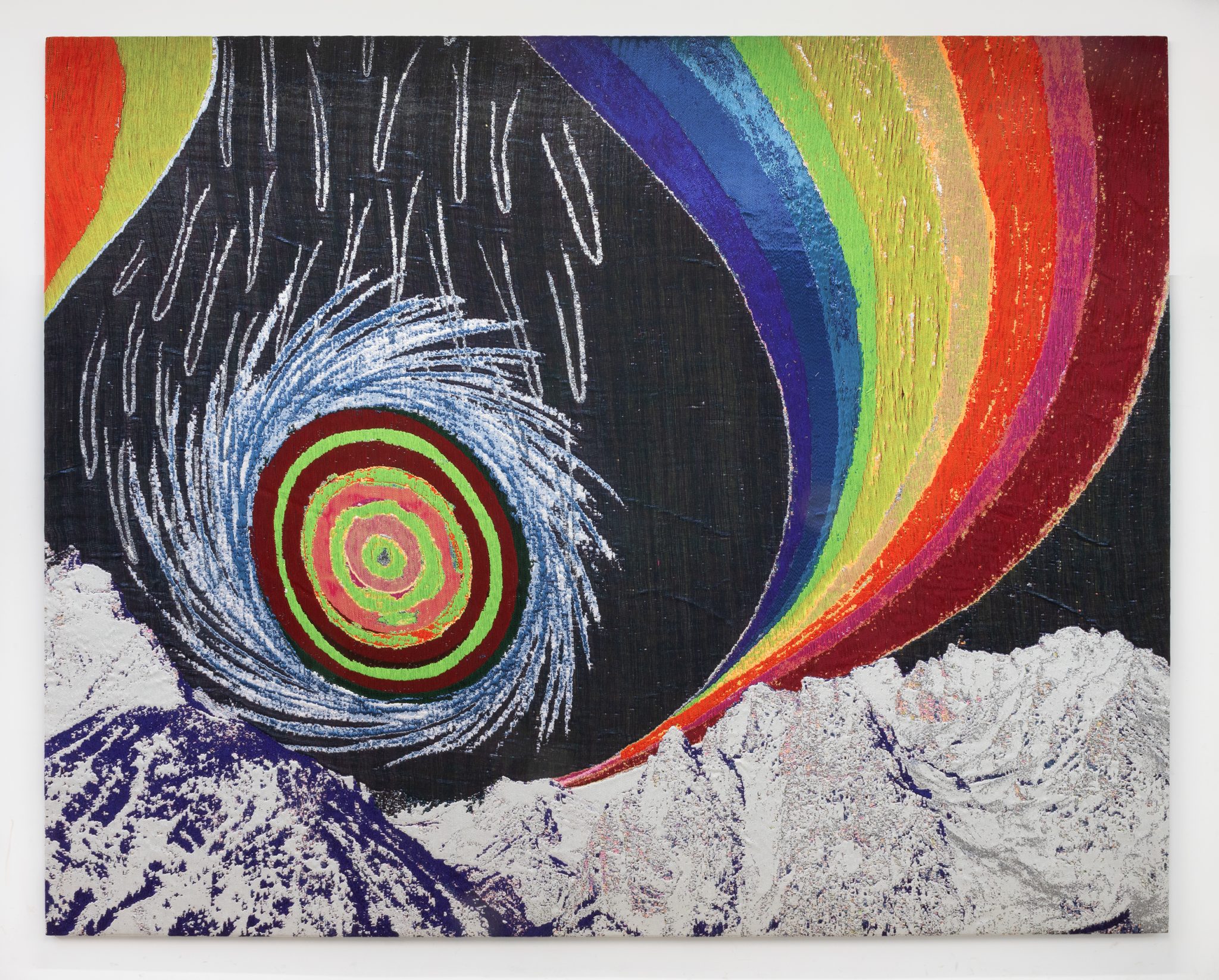

A largescale galactic textile, Rainbow Mountains: Storm (2024), presents a rainbow à la glam rock, a brightly hued and uncompromisingly sized banner framing a winding slab of blue, green, yellow, orange and red that renders the ubiquitous queer symbol and natural phenomenon at once familiar and obscure. Towering over the viewer at a height of three metres, the rainbow feels not only divine but also alive. The tapestry’s physical richness makes the scene almost kinetic: the woven surface seems to breathe. Like a stop on the itinerary of a space-travelling Ziggy Stardust, Collins’s rainbow spreads its bands of colours with a glamorous, irresistible and almost sonic charm. Towards the bottom of the composition lies a mountainous land with views of what resemble snowy peaks. The land beneath the rainbow, where molten earth blends with spiky rocks, radiates a synaesthetic blast. Onto the blast site rain silver droplets: the image on the textile captures the medley of liquid and solid in a moment of both cohesion and disintegration.

Smaller textiles spread around the gallery, which buttress the visual effect of Rainbow Mountains: Storm, zoom in on sharp-edged, flamboyant thunderbolts that poke at waves of bright sequins, showcasing Collins’s signature eclecticism. Fuzzy yarn pushes and pulls against Fractured Sky (2023). A rainbow zigzag composed of beadwork wedges itself between a shiny metallic surface and a matt grid in Fission (2024). Sleek blue circles hover on a stippled woven background in one of three textiles titled Lightning Wheel (2024). Collins’s disparate materials clash with such force and friction they appear at times to be engaged in an erotic dance. Serpentine fibres tug at and bleed into one another. Each sequin beams like a sweat drop and collectively manifests force like a gay army. Different practices of weaving mingle and bond, penetrating one another and releasing. Fleshiness is not an unheard-of attribute for textile – think Sheila Hicks or Faith Ringgold. Collins’s works, however, are less like bodies themselves than like the accreted marks of a body’s rhythms and exertions; they are records of action, both product and process.

Because her work invokes craft traditions and aligns with what the press release calls ‘queer feminist sensibilities’, Collins runs the risk of being pigeonholed as an ‘artist-activist’, a marcher sewing her banner for the street. However, through the roaring stillness of abstraction, Collins’s insistently utopian textiles call to mind the kind of queer openendedness the late cultural theorist José Esteban Muñoz was evoking in Cruising Utopia (2009) when he wrote, ‘Queerness is not yet here but it approaches like a crashing wave of potentiality. And we must give in to its propulsion.’ Numerous political positions can be distilled from Collins’s subject matter and symbology, but in the face of mounting expectations for activist declarations in queer art, Collins also dares to leave the interpretation of her works unfixed: her shapes, colours and textures invite unfettered readings and thus satiate both the mind and the heart.

Lightning Wheel at Candice Madey, New York, 20 June – 2 August