We could be stopping oligarchs from using art to launder money; instead we’re banning Russian film directors and worrying about a statue of Engels

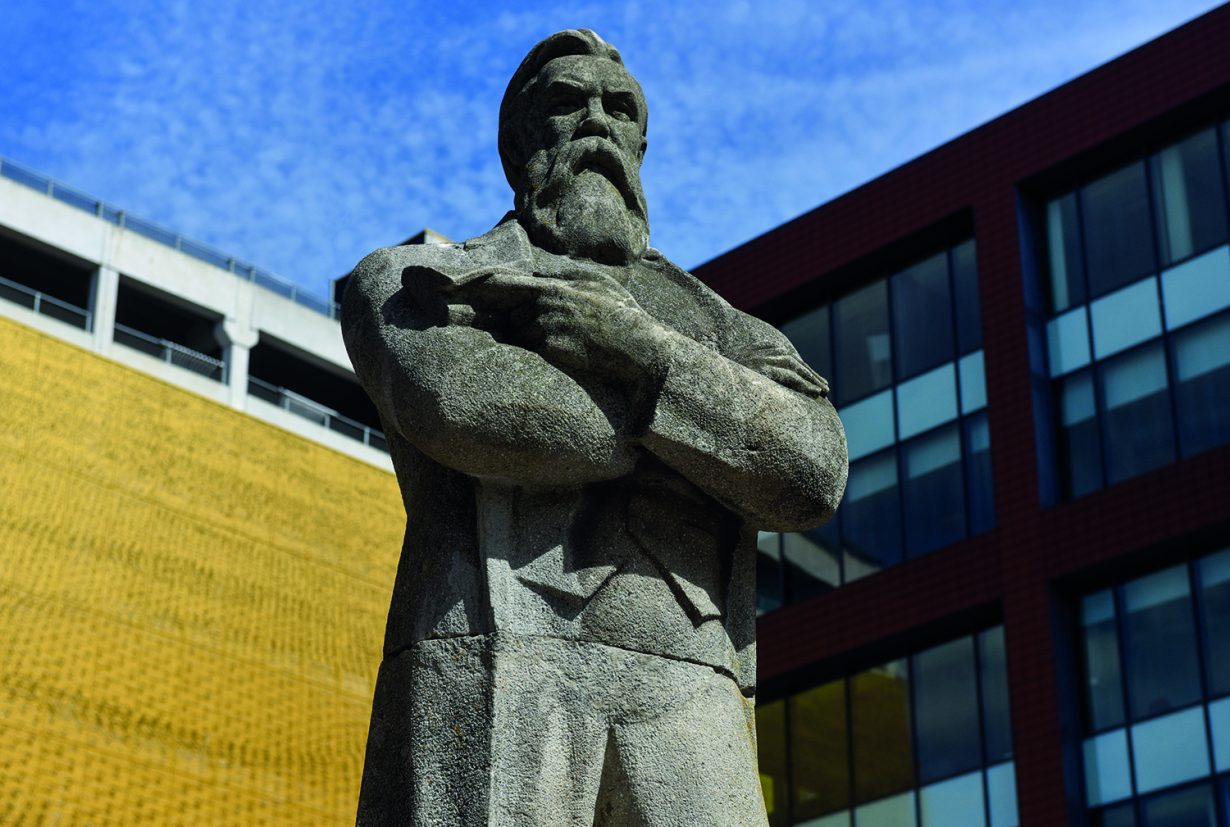

In 2017, the artist Phil Collins transported a statue of Friedrich Engels – the Ringo to Marx’s rest of The Beatles – from the east Ukrainian village of Mala Pereshchepina, where in Soviet times it had stood in the town square, to the centre of Manchester, where it was greeted with hope and joy, as chronicled in Collins’s film Ceremony (2017). It’s still standing in Tony Wilson Place, outside the city’s HOME art centre.

Engels spent much of his life in Manchester, where his (extremely wealthy industrialist) family owned a number of factories (in many ways his thought was exemplary of that most philosophical of all instincts: ‘fuck you dad’). In the early 1840s, just before he started collaborating with Marx, Engels began writing a book based on his observations of poverty there, The Condition of the Working Class in England (originally published in German in 1845). He was helped in this work by Mary Burns, his long-term partner, a working-class Irish woman he met on the factory floor. In Condition, Engels provided the empirical story behind the philosophy which Marx was developing at the time, describing a world in which – to put this in the language of Marx’s 1844 essay ‘Alienated Labour’ – the more workers produce to enrich factory owners like the Engelses, the more said workers ‘lose their own reality,’ to the point of ‘starving to death.’

But despite Engels’s importance, there had never previously been any public monuments in Manchester to his work – in stark contrast to the former Soviet Union, when Engels statues were pretty much everywhere (of course these two facts are very much related). When Collins found the Engels statue in Ukraine, it had been cut in half, and left behind some farm buildings: just old communist-era junk. It had had to come down, but after that, no-one had been quite sure what to do with it – like so much else of the past.

Ceremony is a fascinating film, and not just because it provides viewers with the singularly comic sight of watching this decayed socialist realist Engels statue bobbing west across Europe on the back of a big truck. What it presents to us – and thus, what the Engels statue as it stands in Manchester is able to symbolise on an ongoing basis – is nothing short of the full complexity of the contested legacy of communism today.

Over the course of Engels’ transportation, Collins films the reactions of passers-by. In Ukraine, the statue is gawped at as a relic of a bygone age – he is someone whose ideas, when they were put into practice, failed. To some people, the sight of Engels is a source of nostalgia – his presence really brings them back: the smell of a perfume worn by someone you know rationally you were always going to break up with anyway. Ah, what times Engels and I had! To others, he is not just a funny antiquated curiosity, but rather something actively dangerous: to walk the way to Engels would be to trip backwards into tyranny. But in Manchester, at the peak of the Corbyn movement, he feels like a figure of the future: his ideas are a source of hope. Scenes from austerity Britain intermingle with the statue’s joyous reception – a messenger from another world, a visitor from the new humanity the Soviet revolution once promised, but failed to deliver. Maybe we could do it right next time.

Or who knows – maybe not. Last week, controversy ensued when HOME said that they were in discussions with the artist over the statue in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (leading many to assume that they were planning to remove it). HOME have since issued a statement claiming that taking down the statue was never their intention – they really only wanted to do something to ‘consider its meaning in the context of the illegal invasion of Ukraine’. Which is good, because let’s face it: responding to the illegal invasion of Ukraine by taking down a statue which might well be taken to represent Anglo-Ukrainian friendship, depicting a German thinker whose ideas the rulers of Russia violently reject, would have been really fucking stupid.

Still: while there might not be any direct threat to the Engels statue as such, the incident remains characteristic of what might just be the artworld’s hottest new trend: the well-meaning, but ultimately clumsy and poorly-conceived attempt to reckon with the hell of the war in Ukraine. I’m going to guess that probably, if the artworld really wanted to hit Russia where it hurt, the priority would be to take all necessary steps towards stopping oligarchs from using art sales to launder money. But that hasn’t stopped curators (who, OK, are almost certainly not directly responsible for any actual money laundering) from bravely banning Russian directors from film festivals, or – you know, let’s face it, because despite all post facto protestations, this really was what was going on here – hand-wringing about statues.

With the war in Ukraine, there is an obvious temptation to think in terms of absolutes. What is going on there is horrible, and wrong – shocking, not just because it’s a war (as we’re used to mighty imperial powers, not least Western ones, starting horrific wars) but because it doesn’t even make any sort of realpolitik sense. The invasion must be condemned – of course it must be condemned. Russia must be sanctioned – it’s the only realistic way we’re going to make Putin hurt. But there is nevertheless a temptation, amidst all condemnation and sanctioning of Russia, for this to slide into a taboo on all things Russian. In short for all Russian-ness – up to and including things that just somehow ‘feel’ a little Russian, regardless of whether this feeling is rational or not – to be expunged, to be concealed; to be un-personed out of our cultural lives, to never be spoken of again. (By contrast, the Manchester Evening News was embroiled in their own controversy earlier this week after doing a puffy interview with a ‘Ukrainian hero’ who had ‘fought Stalin’ during World War II – that is, on the side of the Nazis).

And of course this threat is particularly apparent when it comes to figures like Engels. ‘Communism’, as it is described by Marx and Engels in their actual writings, looks about as much like the actual Soviet Union did as it would a bear dancing on the Moon. Marx describes a system which will be brought about by the spontaneous activity of a proletariat who have realised they are the agents of history, who will abolish capitalism and with it themselves; who will take control of the bourgeois state, only to bring the means of production into communal ownership and ultimately see it wither away. Of course something like this was Lenin’s vision (notwithstanding the various tweaks he made to adapt Marxism to Russian conditions). But whatever the Soviet Union actually was (and of course there are many different subtleties of perspective on it that might be admitted, both critical and otherwise) it was not a Communist society as Marx and Engels would have recognised.

For all this though, this is what people think of, typically, when you mention ‘communism’ to them. For Marx, ‘communism’ meant the abolition of private property, and with it the possibility of real equality of freedom, in which the free development of one is the free development of all. For the average person, ‘communism’ is when you do things that are Russian. The more Russian something is, so the more communist it is too – and vice versa.

For a while at least, this logic seemed likely to do for the Engels statue outside HOME – a communist thing, thus a Russian thing, that had stood in Ukraine: a cipher for the illegal invasion. And yet, ironically enough, the remedy for all this nonsense ought to be Collins’s own film.

Ceremony presents Engels exactly as he should be: as an ambiguous, contested figure – at once a revolutionary theorist, and a bourgeois factory owner; at once the source of new dreams, and a symbol of the old despair. For Engels, for socialism, so for everything else – not least, the strength of humanity’s ongoing commitment not to be obliterated by nuclear war. Only in the space allowed by this sort of ambiguity, will hope and freedom ever have room to grow. If the war in Ukraine is a call to act, then the controversy over the Engels statue is a reminder that this action will be worth less than nothing, unless it’s premised on a commitment to stop being so stupid about everything.