From Whitney and Sydney Biennial to March Meeting in Sharjah, our editors on what they’re looking forward to this month

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing

The Whitney, New York, 20 March–11 August

The initial announcement of the lead curators two years ago already signalled some of the scope of the biennial, with Chrissie Iles a more institutional voice and Meg Onli, who had been curator at LA’s Underground Museum, a more millennial perspective. They’ve since ramped up the curatorial party, bringing in a range of other curators and artists (among them Taja Cheek, aka L’Rain, Zachary Druker and filmmaker asinnajaq) to host a suite of music, film and performance events. This expanded curatorial Borg has said that the selection of those featured revolves around ‘the real’, whatever that means, but the central list of seventy-one artists and collectives brings in some feminist art heavies like Harmony Hammond and Mary Kelly, and established names like Isaac Julien, alongside younger artists like Mongolian filmmaker Zulaa Urchuud and Samí artist and storyteller Niillasaš-Jovnna Máreha Juhani Sunná Máret–Sunna Nousuniemi. Though in the stats the Millennials win, with over a third of the artists presenting being born in the 1980s, like Holly Herndon and Matt Dryhurst’s AI tools and the delicate, unfurling media-swapping of Lotus L. Kang’s installations. Real, indeed. Chris Fite-Wassilak

Libby Heaney: Quantum Soup

HEK, Basel, 23 March–26 May

Of all the artists whose works sit at the junctions between art and science, Libby Heaney is actually a scientist putting her PhD in quantum physics to use. After eight years at scientific institutions like Oxford and the National University of Singapore, Heaney left the field as art seemed to afford her more ‘freedom to discuss and critically question technological developments from a broader perspective’. Heaney’s groundbreaking and immersive works utilise quantum computers, which operate outside the logic of binary code, to create an accessible look into the ‘quantum world’. What transpires, then, are futuristic and vibrant digiscapes at once alien and familiar. For her first solo exhibition in Switzerland at HEK titled, Quantum Soup, Heaney will be presenting video installations, game-environments and VR experiences developed with the quantum computer. What is different about these works, than say any other new media, you may ask? Well, maybe see the show and find out. Marv Recinto

TONO Festival 2024

Mexico City & Puebla, 12–24 March

Tono launched in Mexico City last year as a new festival for ‘time-based artwork’, namely performance, dance, music and video art by local and international artists in partnership with museums and galleries across the city – all orchestrated by curator and writer Samantha Ozer. Unsurprisingly, a lineup featuring artists like Arthur Jafa, Wangshui, Naomi Rincón Gallardo and Meriem Bennani drew considerable attention, and speaks both to the benefits of institutional backing to support the local, burgeoning performance scene – and the expanse of Ozer’s rolodex. So Tono returns this year with just as much pop for your peso: Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Ali Cherri, (LA)HORDE, Gabriel Massan, Seba Calfuqueo. I’ll be seated for Joshua Serafin, whose performances – of the tactile natural world; of bodies writhing in dreams and nightmares; of fluids and muscle and glimmer – are at once stern, arresting and explosively camp. Alexander Leissle

March Meeting 2024: Tawashujat

Khalid Bin Mohammed School, Al Manakh, Sharjah, 1–3 March

The sixteenth annual gathering/think tank of artists and academics in the Emirate is titled Tawashujat, an Arabic word that refers to ‘coming together or intertwining’, which further translated into artworld speak means collective practice. Sound familiar? This is in a way a coda to Documenta 15. So you’ll find workshops, panel discussions and performances featuring representatives of Indonesia’s ruangrupa (who curated that last edition of Documenta), Bangladesh’s Britto Arts Trust, India’s RAQS Media Collective, Sengal’s Raw Materials Company, Korea’s ikkibawiKrrr and the Palestine Writing Workshop, alongside many others. And even the odd solo operator such as octogenarian political commentator and all-round public intellectual Tariq Ali. If you get bored of all the chatter, however, there are exhibitions too: among them solo shows of work by the late Pakistani artist Lala Rukh, and by Ethiopian telsem artist Henok Melkamzer; a survey show of artists involved in Morocco’s Casablanca Art School, and perhaps, more urgently, of works documenting or informing audiences about the history of Palestine from the Sharjah Art Foundation collection, titled In the eyes of our present, we hear Palestine. Nirmala Devi

Yokohama Triennale: Wild Grass: Our Lives

Yokohama Museum of Art, 15 March–9 June

‘Wild grass strikes no deep roots,’ wrote the Chinese writer Lu Xun in the foreword to his collection of prose poems Wild Grass (1924–26). It has ‘no beautiful flowers and leaves, yet it imbibes dew, water and the blood and flesh of the dead… As long as it lives it is trampled upon and mown down, until it dies and decays.’ This somewhat macabre thought forms the basis to the theme of this year’s Yokohama Triennale – curated by artist Liu Ding and art-historian Carol Yinghua Lu – which broadly centres on how humanity has continually found ways to survive major historical crises. And how, from those examples, we might learn to survive present global conditions of political, social and ecological turmoil. At least according to the press release, which reads more like the manufactured sprawl of an 18-hole golf course than a wild meadow – beginning with the failure of social infrastructures during the COVID-19 pandemic and meandering through climate change, the rise of nationalism, conspiracies, war, class inequalities, etc. Still though, there’s apparently ample room to explore those topics via five venues and the work of 94 artists (including Hong Kong musician Xper.XR, the late artists Ryuichi Sakamoto and Pope.L, game-engine artist Kim Heecheon and performance/installation artist Puppies Puppies). It’ll be tough to remain on par with such a wide range of global problems – let’s hope Wild Grass doesn’t end up in the rough. Fi Churchman

Crafting Modernity: Design in Latin America, 1940–1980

MoMA, New York, 8 March–22 September

Some May Work as Symbols: Art Made in Brazil, 1950s–70s

Raven Row, London, 7 March–5 May

Historically whenever MoMA staged a sweeping survey of Latin America, or the art and design of the continent’s constituent countries, it was done so with a nod, wink, and sometimes even hard cash, of the US state department; the museum acting as a curatorial outrider for Washington foreign policy, whether cultivating ‘good neighbours’ during the war years or pushing back on the red devil in the later twentieth century. It will be interesting then whether institutional self-reflection enters this survey of design, which ranges from the 1960s pop sensibilities of Chilean painter Roberto Matta’s forays into product design to the indigenous-inflected design of Brazilian Lina Bo Bardi. Opening concurrently across the Atlantic is Some May Work as Symbols, where Londoners get to compare the symbolism at play in the work of Bo Bardi’s peers with a deeply researched show including Brazilian concretists and neoconcretists – such as Judith Lauand, Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica – and those associated with the Afro-Brazilian aesthetic (and its debt to the Candomblé religion), developed in the same period by the likes of Mestre Didi, Abdias Nascimento and Rubem Valentim. Oliver Basciano

24th Biennale of Sydney: Ten Thousand Suns

White Bay Power Station, Sydney, 9 March–10 June

Increasingly, the artworld – and biennial curators in particular – finds itself caught up in the feeling that it should address global, catastrophic issues. The Big Ones. Sometimes that looks a bit like trying to justify why it should take up an audience’s attention (an insecurity, let’s say, about art’s usefulness in addressing social, political and environmental destruction). Often it’s done with a sort of sombre, academic earnestness (see Yokohama Triennial’s Wild Grass). Not so, apparently, this year’s edition of the Biennale of Sydney. Ten Thousand Suns promises to burn through the gloom by focusing on the many ways in which celebration can be as much about joy as about resistance and resilience in the face of disaster and adversity. Drawing on ‘multiple histories, voices and perspectives’, Ten Thousand Suns plans to shine light on First Nations knowledges, rejecting ‘Western fatalistic constructions of the apocalypse’. (Although: the famed verse that shatterer-of-worlds Robert Oppenheimer borrowed from the Bhagavad Gita – ‘I am become Death…’ – begins, ‘If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst in the sky, that would be like the splendour of the mighty one’, so you could say that the biennial title chimes with Eastern constructions of the apocalypse.) On show will be the work of 88 artists from 47 countries whose practices are ‘firmly rooted in diverse communities and artistic vocabularies’ – including Kaylene Whiskey, Megan Cope, Anne Samat, Serwah Attafuah and Pacific Sisters. Fi Churchman

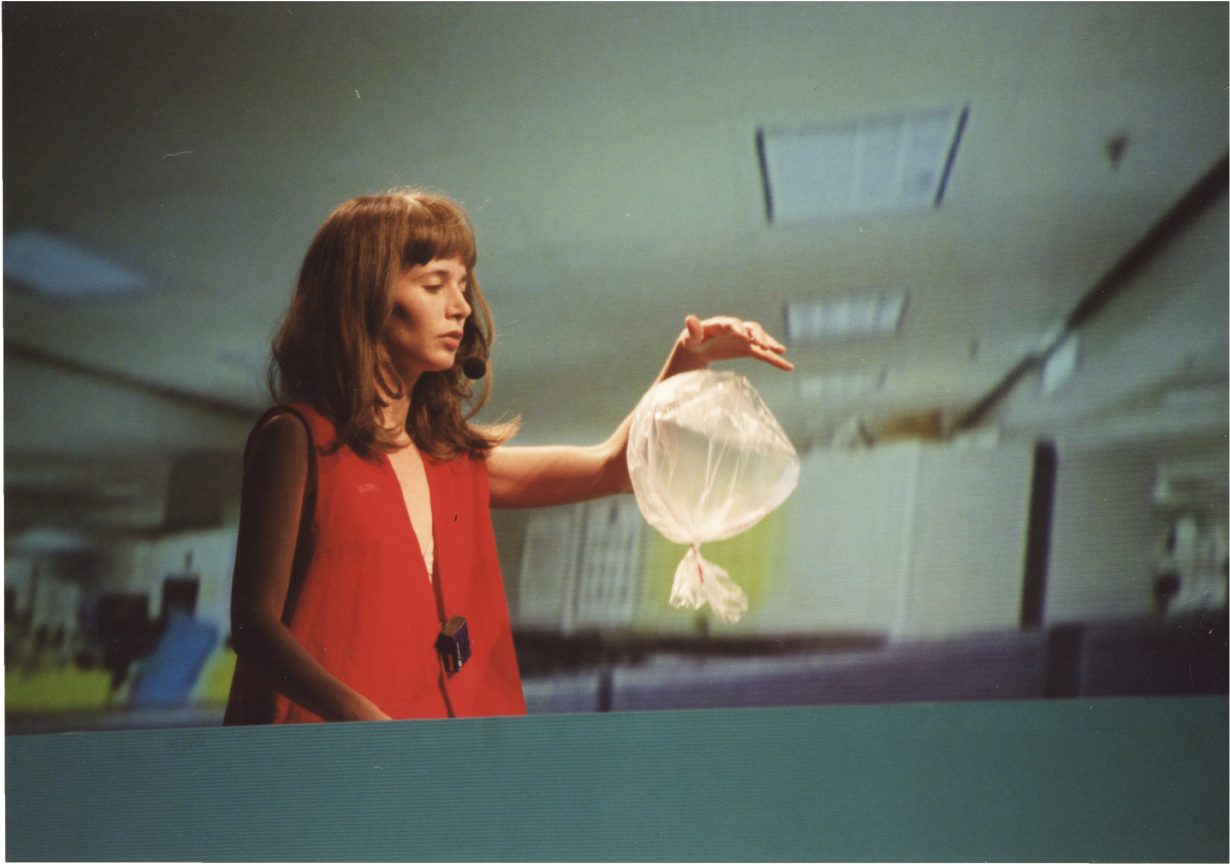

Miranda July: New Society

Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, Milan, 7 March–14 October

Artist, filmmaker, actor, writer, musician, performer – it’s hard to box Miranda July into any one category other than the one she has created for herself. Los Angeles curator Mia Locks is giving it a go however, boxing three-decades of work by the American polymath (who has said that her adopted surname was ‘a teenager’s idea of a good name’) into what’s billed as her ‘first solo museum exhibition’ in Milan. That said, July’s no stranger to the artworld, having exhibited her interactive sculptures Eleven Heavy Things during the Venice Biennale in 2009 (and subsequently toured them around the US). That work, like much of July’s output, revolves around core themes of human relationships and the creation of intimacy while the show as a whole will focus on her ongoing interest in questioning or subverting supposedly fixed social hierarchies from a feminist position. In addition, July will debut a new video installation – F.A.M.I.L.Y. (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You) – and her entire filmography (film being the medium for which she is perhaps best known, having picked up a Camera d’Or at Cannes and a Special Jury Prize at Sundance) will be screened in the Fondazione’s cinema during the coming month. Nirmala Devi

Ulises Carrión: Dear reader. Don’t read

Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, 16 March–10 October

Ever dreamt of quitting it all and starting a bookshop? Maybe take inspiration from the notebook of Mexican conceptual artist Ulises Carrión, whose Other Books and So (1975–79) was a ‘legendary bookshop-gallery’ in Amsterdam, exclusively dedicated to ‘other books, non books, anti books, pseudo books, quasi books, concrete books, conceptual books, structural books, project books, plain books’, as indicated in its opening announcement. The project, however, was not only a commercial one for Carrió, but also an artwork in itself – and alludes to his rich conceptual practice that has earned him the reputation of being among Mexico’s most important conceptual artists. Reina Sofía will display nearly 350 works from his prolific career – including ‘books, magazines, videos, films, sound pieces, mail art, public projects, and performances, along with Carrión’s initiatives as curator, editor, distributor, lecturer, archivist, art theorist, and writer’. While this show seems decidedly like an archival show, there’s no way to separate the artist’s prolific conceptual practice from his print one. Marv Recinto

The Shadow Ring (1992-2002)

Blank Forms Editions, 15 March

The term ‘avant-rock’ has to work hard to cover just how far The Shadow Ring managed to break music during its obscure ten-year wanderings through the 1990s, a group so underground that the term ‘sub-underground’ had to be invented for them. Formed in Cheriton, one of the most boring suburbs of Kent, England, by Graham Lambkin and Darren Harris (later joined by Tim Goss), and recording initially out Lambkin’s parents’ house, the group formed a kind of anti-music that eschewed any pretence of experimental flamboyance. Whether the group could play their instruments – or even manage to tune them properly – was a moot point, or rather a challenge they threw at any normal view of musical or lyrical competence. Pot and pans used as drums, guitar riffs warping and sagging, pianos and synthesisers played as if they’d just stumbled into the things for the first time, and with an unerring lack of rhythm, shaped around Lambkin’s awkward spoken-word, post-apocalyptic depressive musings, The Shadow Ring conjured a sense of existence situated somewhere between the local convenience store and watching exhausted stars imploding. US experimental imprint Blank Forms perform the feat of putting it all together in this 11-CD, one DVD (and 450-page book box set). All ArtReview needs now is some kind of hi-fi to play it on. J.J. Charlesworth